The Journeys End

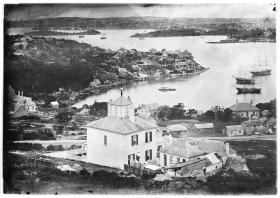

At last, the final two wet-plate glass negatives from the Holtermann Collection have been digitised. They are over a metre long (1.36m x 0.95m) and were made in 1875 from inside Holtermann's residence, known as "Holtermann's Tower" in St Leonards. The negatives display views of Sydney Harbour, Garden Island to Millers Point, from Lavender Bay.

These plates are the final and most challenging plates to be digitised from the World Heritage listed Holtermann Glass Plate Collection. It is comprised of around 3,500 wet glass plate negatives of varying sizes made by Holtermann's photographer's Charles Bayliss and Beaufoy Merlin over the period 1871-1876.

The digitisation process of this considerable collection began as an initiative of Imaging Services Manager Scott Wajon in 2009. The Collection had been digitised previously as "copy negatives"; Scott saw these and realised they had nothing like the detail that could be achieved with our current equipment. Thanks to Scott's perseverance and the successful fundraising coordinated through the Library’s Foundation, a dedicated team of talented people began digitising the whole Holtermann negative collection - starting from the smallest and ending here, with the digitisation of the largest historical wet plate negatives currently know to exist. The negatives have been digitised to reveal a spectacular level of detail and are available for viewing on the library's website.

How did we do it?

It was a challenge to digitise such enormous negatives. They took three days to shoot and much longer for preparation. It required the cooperation of a large multi skilled team, a combination of some high end equipment and considerable ingenuity. The challenges of digitising these glass plates were many and varied, not least of all the potentially hazardous combination of size, age, unwieldiness and fragile emulsion.

A small group that included Alan Davies the Library's curator of Photography and members of the conservation team wheeled the enormous wooden box into the Imaging studio. As the first plate was carefully removed from its home, the nervous and excited team looked on. The plate was, much to everyone's relief, successfully and deftly fitted snugly into its custom built, rigid, vertical support. It was built this way because the sheer weight of the negative could have caused the glass to break had it been laid out horizontally. As with a standard negative, light was needed to bring the scene to life. Behind the negative a custom made light box with daylight balanced keno's was switched on illuminating the enormous negative and its incredibly detailed landscape of a very young Sydney Harbour.

After all the camera attachments had been made, the overhead lights were switched off and all that could be seen was the glowing negative and the expression of concentration on the Hamilton's face bathed in light as he cautiously shot each segment, checking the results onscreen before moving on to the next shot. This process was painstakingly carried out for both negatives.

You can find out more about this collection in The Holtermann Collection story.

A number of people need a special mention for making this final stage of the project a success:

- Imaging Services Team

- Conservation team

- Fraser and Mark from Pod design for building the support structure and moving the negative

- Lester and Morgan from Black Bishop Films from providing and controlling the dolly

- Susan Hunt, from SLNSW Foundation, who have supported the project from its inception