Perfecting the portrait

Photographic retouching has become widely accessible in recent years thanks to the increasing ease of use of image editing programs. A variety of tools are available in our virtual palette and mistakes can be easily reversed by simply telling the program to Undo please! Retouching in the late 19th century was a far cry from this clean, trial-and-error method we have become so dependant on and would likely give the imaging specialists of today nightmares.

The collodion era saw retouching become mainstream. Prior to this the delicate surface of the Daguerreotype could not withstand the process (apart form tinting or colouring). The results of retouching directly applied to the collodion paper print were not ideal and photographers even attempted to “retouch” the model prior to photography as noted in The studio and what to do in it H.P. Robinson 1891.

“all kinds of powders and cosmetics were brought into play, until sitters did not think they were being properly treated if their faces and hair were not powdered until they looked like a ghastly mockery of the clown in a pantomime.”

The retouching was eventually applied to the collodion negative itself offering a much more natural looking result. Collodion negative retouching was thought to have become general practice during the 1860s although some believed the practice had been secretly in use earlier.

“A case may be remembered, many years ago, at a photographic exhibition, when the fine contributions of a very able photographer [probably T.R. Williams] were challenged by another portraitist as being retouched. The response to this was an offer to permit the prints to be sponged with water. The challenger insisted that the stippling was manifest beyond question when the prints were examined by a magnifying glass. The production of unmounted prints with precisely similar gradation, which was not removed by sponging, seemed to settle the matter by deciding that there could be no retouching, the negatives never begin suspected.” [1]

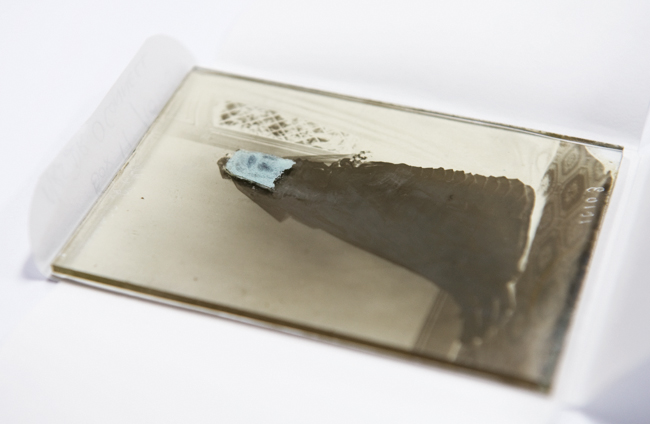

The requirements of a retoucher were listed by J.P. Ourdan [2] as, “a retouching desk, a supply of pencils of various grades, a magnifying glass, several small brushes, stumps of paper and leather, a few cakes of water color, viz., neutral tint, Indian red and carmine, and a bottle of a good, hard matt varnish.” The American and Australasian Photographic Company used a blue pigment most likely suspended in a solution of gum arabic or gum tragacanth in the manner of thick water colours. [3]

They lightly abraded the varnished emulsion surface of the area to be retouched and then carefully stippled this solution onto the emulsion at varying densities to cover up dark shadows, freckles and other blemishes caused either by poor lighting (remember, natural light from a sky light had to be used) or a particularly blemished subject.

When printed the inked areas would appear lighter and when viewed at their original carte de visite size the stippling would have the effect of hiding the blemishes and evening out skintones. Because the scans for our digitisation project are so highly detailed we can view the retouching closely and see the stippling method used by the A&A retoucher – see image to left.

When printed the inked areas would appear lighter and when viewed at their original carte de visite size the stippling would have the effect of hiding the blemishes and evening out skintones. Because the scans for our digitisation project are so highly detailed we can view the retouching closely and see the stippling method used by the A&A retoucher – see image to left.

The retoucher had to be careful not to overdo his work as too much of a good thing could create a result as below described.

“ They neatly fill up wrinkles and scars and soften shadows, until they produce a face almost as smooth and quite as expressionless as a billiard ball. And what is more, they are proud of the result!” [1]

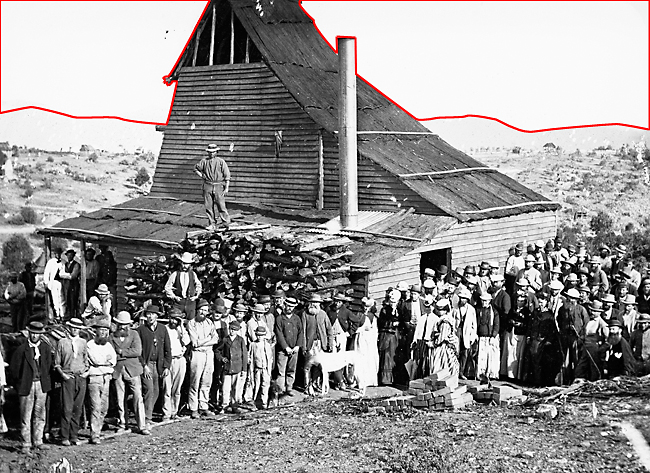

Another type of retouching we see in A&A's work is the use of masks of very thin paper to whiten large areas of sky. The paper would be cut into an appropriately shaped mask and then glued to the glass plate side of the negative, as shown below. The red line indicates the area covered by the mask in this image. Sometimes the retoucher would even paint in clouds by smudging ink onto the glass in cloud-like shapes, although this is not seen commonly in the Holtermann collection negatives.

The reason this masking was necessary at all is that collodion negatives are orthochromatic, meaning they are sensitive to only the blue part of the spectrum. This meant that when photographed blue objects would appear much brighter than when seen by the naked eye. This resulted in portrait models with blue eyes photographing as the piercing pale eyes seen in many A&A portraits. Patrons of photographic portrait studios using collodion film would often be advised to steer away from blue clothing to avoid unwanted results in the finished piece.

In rare cases these thin paper masks would be used to filter contrasty areas of a negative during printing. One extreme example of this is the below portrait of Mrs O'Connell in her wedding dress.

Her face was masked, which originally would have helped to bring the contrast and brightness of her shadowed face in line with that of her white dress. Over the last century the paper has become more cloudy so that now it creates a overpowering mask that obscures her face to a degree. After careful consideration and consultation we decided that we could capture the information in the negative more accurately by removing the mask in our Preservation department. We documented the original retouching well and now have an interesting comparison between our scans, with and without the retouching mask.

It is interesting to note that, even in the days of the American and Australasian Photographic Company there has been controversy over the use of retouching “by photographic purists as a departure from the truth as it is in photography.” [1] I'm sure we can find H.P. Robinson's “billiard ball” face - free of lines and texture - in nearly any fashion magazine on the rack today. He also notes in 1891 that “others hope that the mania for retouching will run its course.” If only he knew!

[1] The studio and what to do in it H.P. Robinson 1891

[2] The art of retouching J.P. Ourdan 1880

[3] "Red skies and blackened cheeks" The Collodion Journal 5(17) Mark Osterman

Words by Lauren O'Brien.