Shepherding without sheep

A recent blog – Coffee or me? - described the owner of a coffee shop as having a series of jobs, “from shepherding on the Star to teaching in school”.

In the context of gold mining, shepherding had nothing to do with guarding a ruminant flock.

Essentially it was care taking a claim.

It’s probably necessary to explain a few mining terms of the period and the process of claims to understand how shepherding came about.

Prospectors bought a licence, which gave them some protection from other prospectors until gold was discovered and a lead (a run of gold beneath the surface in an ancient river bed) proclaimed. In the meantime, prospectors could sink as many shafts as they liked on their protected claim.

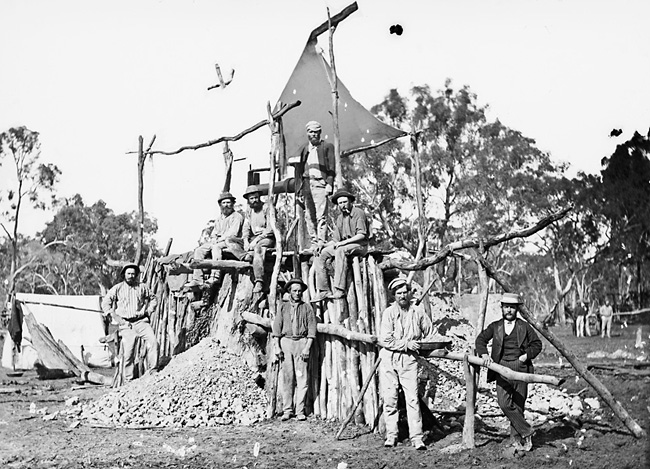

Gold miners strike a new claim at the mine head. Holtermann negative 18269, box 3.

A frontage claim was proclaimed on a lead, when three shafts averaged over 100 feet [30.5 metres] to bottom on gold bearing material. A frontage claim was for six men totalling 240 feet [73 metres] and half a mile [805 metres] either side of the baseline pegged by the gold commissioner. After payable gold was struck within the claim, the claim holders were required to select their block, the rest of the claim being available to other miners.

A block claim was proclaimed on a lead if three shafts bottomed less than 100 feet deep. The claim was for four men, 240x125 feet [73x38metres], marked off in sequence along the lead. This was preferred, as it favoured more miners.

When a shaft bottomed, miners had to report it to the commissioner and raise a red flag at the shaft. A sequence of red flags would thus define the direction of the gold lead and create excitement or despair on adjoining claims, depending on the direction of the red line. Regulations also stated that miners or their representatives holding licences had to be present on the claim every day between the hours of nine and eleven o’clock, except public holidays.

Gold miners at shaft with red flag displayed. Holtermann negative 18426, box 3.

Failure to observe the regulations meant that claims could legally be jumped by other miners. The law also permitted the jumping of unworked claims if miners or their representatives were not present on the claim between the regulated hours.

An early description of shepherding unworked claims is to be found in an 1857 pamphlet about gold mining in Victoria.[1]

"About this time the first Local Court was established at Ballarat. This popular institution was one of the results of the Eureka Stockade movement, and was intended to have the management of mining matters, the presumption being that, as its members consisted of practical miners, an improved system of mining legislation would be introduced that would lead to a fuller development of the resources of the gold fields generally. Nearly the first act of the Local Court was the abolition of the practice of “shepherding,” or holding claims in reserve and unworked; by which practice one man would mark out as much ground as was apportioned to eight men, which he would keep possession of until the course of the gutter was proved by those who worked instead of shepherding. If the gutter seemed likely to approach the shepherd’s claim, a matter which, from the sinuosities of the lead, will at once be seen to be uncertain until the ground had been proved to within a short distance of the claim held in reserve, the shepherd would sell shares in his eight-share claim, and in many instances a good round sum would be obtained without the vulgar interposition of hard work. With the basaltic hill before the miners at Frenchman’s, it became a question - how could men afford to sink without a guarantee of the gutter? Under the old system it was known that, for one party who would strike the gutter, twenty might be ruined; and the attention of’ those interested was given to the matter as one of vital importance to the miner. After several meetings had been held, Mr Bacon suggested the adoption of a plan which had been mooted previously; but it had met with such vehement opposition, that it had to be relinquished.

This plan was to use a definite length of the gutter to each party, and to mark the claims across the course of the gutter, instead of the old method of square blocks. Finally the thing was carried in the Local Court by a majority of one, and thus the frontage system of claims became law."

Unfortunately, there was no simple solution to prevent shepherding, despite numerous changes to the regulations, and in 1874 the NSW Mining Board estimated that

"five-sixths of the mining population were kept in compulsory idleness… the system had the effect of converting industrious miners into professional shepherds, as the enforced idleness tended of necessity to weaken industry."[2]

The previous year, a Gulgong miner, under the optimistic pseudonym ORO, wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald, critical of the latest mining bill. He also pointed out one of the consequences of shepherding.

"In dealing with section 14 of this bill I hope the Legislature will define closely who can hold a miner’s right. In the Act of 1861 no person under 14 years of age could hold a miner’s right but Mr Bowie Wilson, in his unique effort at mining reform in 1866, struck out this wise restriction, so that any person can now hold a miner’s right. One pernicious result of this omission is that children of tender years, from 3 to 12 years old, have usurped the place of miners in shepherding claims on frontage leads. On Gulgong, and other gold-fields, it is no uncommon sight to see a girl of 10 or 12 years old, sitting in a rough gunyah in the bush, with four or five men, shepherding a claim The conversation that is indulged in is not calculated to improve her morals, and, if rumour be true, acts result from this demoralising intercourse that I need not describe. I have seen four children under 12 occupying a claim according to law when they should have been at school preparing themselves to fight their way through the world as good men and women. To my mind, it is shocking to contemplate the temptations to which these female children are liable in their daily task of two hours retirement in the bush, under no parental control, and subject to the evil communications of their "mates". While I would not prevent any person holding a miner’s right, I would earnestly suggest that a provision should exist that no female be employed in any capacity on a claim, or any male under fourteen years of age. This would abolish a grave abuse now rampant on every gold- field where the frontage system of occupying claims is in force, and be hailed a stunning reform of a tangible character. Section 15 the provision enabling one man to take possession of claims for other persons, should be omitted, as repugnant to good government and the equitable pursuit of gold-mining. First come first served is the recognised rule of every gold producing country relating to the occupation of claims."[3]

NSW Mining Boards regularly decried shepherding, but did not seem to be able to prevent it. Even the Temora gold rush a decade later was plagued by the practice.

"The great curse of the rush is the system known as "shepherding”. There are plenty of men at Temora who hold as many as a dozen different pieces of ground under their miners’ rights, and as many business sites. These they sell, and make a handsome profit. There were several spots pointed out to me by miners, as really good localities, which had been taken up and absolutely abandoned, but the miners have such an objection to jumping, as a rule, that outsiders do not care about interfering with any ground which others have a shadow of a claim to. There will, however, be an end to this game when the place becomes more settled."[4]

[1] Gold mining on Sebastopol Hill, Ballarat: prepared by order of the Committee of the Frenchman's and White Horse leads, for the benefit of the Ballarat Hospital. 1857

[2] Sydney Morning Herald 2 July 1874

[3] Sydney Morning Herald 8 December 1873

[4] Sydney Morning Herald 9 August 1880

Words by Alan Davies