Sizing up the collection

The Holtermann Collection Digitisation Project is focused mainly on the original glass plate negatives taken by the American & Australasian Photographic Co, although several albums of their 1870s photographs exist at PXA365 and PXD352, as well as more recent prints from all the negatives. Nevertheless, there is great diversity in these glass plate negatives, which we will look at in this week's blog.

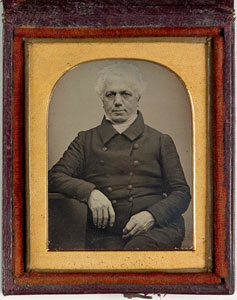

The majority of the negatives (approximately 3100) are quarter plate size, approximately 3.25 x 4.25 inches [83x108mm] and were used to create albumen prints known as cartes de visite - a cheap and popular way for photographers to make personal prints available to the masses, usually presented to the client in a small cardboard mount.

The term "quarter plate" comes from the days of the daguerreotype - the prevalent photographic technology before the introduction of the wet-collodion process in 1854. The first metal plates (copper coated with polished silver) manufactured for the daguerreotype were approximately 6.5 x 8.5 inches [165x216mm], known as full plate or whole plate - smaller sizes were measured as a fraction of that full plate size, e.g half plate, quarter plate. As glass plates came into use, they followed this terminology. Even these standard plate sizes varied with collodion negatives as the glass was usually cut by the  photographer from larger sheets of glass, as was the case with Merlin and Bayliss.

photographer from larger sheets of glass, as was the case with Merlin and Bayliss.

The collection also contains a range of negatives smaller than whole plate, including some stereographic negatives, but of most interest are several hundred larger plates, ranging from 10 x 12 inches [25x30cm] to 18 x 22 inches [46x56cm]. These larger sizes are known as mammoth plates and are very rare in Australia.

From the 1860s it was possible to enlarge negatives using a solar enlarger, which used a clockwork motor to follow the sun. However the results were usually quite poor and often out-of-focus, so photographers found it better to create big photographs by contact printing huge negatives. Of course, big negatives required big cameras and considerable skill was needed to manipulate the wet plate negatives. These large contact prints are incredibly sharp due to the inherently grainless nature of the collodion emulsion and their direct contact with the albumen paper during exposure.

This is especially true for the largest negatives in the collection - measuring 1.6 x 0.9 metres each - the largest wet plate negatives in the world. The library holds a contact print made from one of these negatives that reveals the clarity and detail captured by Merlin and Bayliss in the 1870s. We will post a more detailed look at the mechanics of exposing and processing these larger-than-mammoth negatives when their digitisation is imminent.

Stay tuned for a look into the wet-collodion process in next week's post.