What is History? A guide for primary teachers.

This resource was developed by Dr Jennifer Lawless, State Library of NSW Fellow 2016.

Overview

From 2016, the new History syllabus K-6 replaces the HSIE strand of Change and Continuity. Much of the content is similar to what has been taught in the past, though there is greater emphasis on the development of historical skills and concepts.

This program, along with the accompanying programs for Early Stage 1, Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3, has been developed to assist primary school teachers to master these changes.

What is History - and the role of the Historian?

The following is a brief introduction to the nature of history and what we need to consider when teaching History to primary students. The different types of sources are introduced and teachers may wish to explore the Library’s collection to familiarise themselves with possible sources that could be included in their teaching.

Much of the content in the new History syllabus is similar to that in the previous Change and Continuity strand.

What is Similar?

- Personal, family and community History

- An Inquiry approach

- Australia’s Indigenous and colonial History and how Australia became a nation.

What is Different?

- History replaces the strand Change and Continuity

- There is a change in emphasis from What do we know? to How do we know?

- There is more emphasis on the development of historical concepts including:

- continuity and change

- cause and effect

- perspectives

- empathetic understanding

- significance

- contestability.

- There is more emphasis on the development of historical skills including:

- comprehension: chronology, terms & concepts

- analysis and use of sources

- perspectives & interpretations

- empathetic understanding

- research

- explanation & communication.

- Both concepts and skills are now placed in a Years K-10 continuum

HSIE to History

The following table provides a brief comparison of the topics from the previous Change and Continuity strand of HSIE and the new History topics for each Stage. Much of the content is similar:

| Stage | Change & Continuity Strand | New History Topics |

|---|---|---|

| Early Stage 1 |

Personal & family origins Significant places Changes in own lives & local places Current events & issues |

Personal & Family Histories

|

| Stage 1 |

Family stories Present & past ways of life Important days Historical places & events |

Present & Past Family Life

The Past in the Present

|

| Stage 2 |

Heritage Aboriginal history Capt. Cook & early contact Early colonial life Continuity & Change in family life & communities |

Community & Remembrance

First Contacts

|

| Stage 3 |

Special days Colonial life Development of Australian democracy Federation Human rights & citizenship |

The Australian Colonies

Australia as a Nation

|

Teachers need to be aware of the methodology of historians and how to effectively introduce the skills and concepts to their students.

The work of historians

How do historians investigate the past?

Students should have the opportunities to be introduced to the methods used by historians to investigate the past, to use primary and secondary sources to gather evidence to answer questions about the past and to understand historical and heritage issues. Students should begin to comprehend and express themselves in the particular language of history and ask questions of the past and to undertake an inquiry or investigation into what happened in the past.

At its most basic level, history is everything that has happened in the past. It is also an inquiry or investigation into that past. An investigation into the past requires historians to ask questions. The finished product of an historian’s inquiry is also called history. It is an historian’s interpretation of what happened, based on their investigation and research. These histories are shaped by the kind of questions asked about the past and by the sources and evidence used.

New research and perspectives ensure that history is never static and unchanging.

Perspectives

Each historian writes about the past from a particular point of view. They can be influenced by gender, age, family and heritage background, education, religion, values and political beliefs, life experiences and the time in which they lived. It also depends on what sources they have consulted. Australia’s involvement at Gallipoli in WWI has traditionally focussed on our ‘baptism by fire’, our emergence as a nation, and various heroic themes such as the story of Simpson and his donkey. Very little has been written on the Turkish perspective, the experiences of the young men captured as prisoners of war or the role of the nurses nearby. The campaign is rarely described as an invasion of a foreign land and a campaign that ultimately failed.

Historians need to consider some of the following when commencing the research of a topic:

- how do we know what happened?

- what evidence is left?

- what does the evidence tell us?

- what is fact and what is opinion?

- whose version of what happened is reliable?

- is there more than one perspective to examine?

- why did particular events happen?

- is there more than one explanation?

- what were the consequences?

- were the consequences the same for everyone?

Sources v Evidence

Historians base their research on sources that are relevant to their inquiry. They need to analyse them to discover if they hold any relevant evidence for their inquiry.

An historical source could be an official document, letter, coin, pottery, newspaper, a burial, building, weapon, gravestone, letter, inscription.

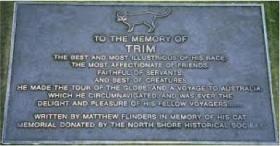

Consider the example below.

The source is the memorial plaque. The evidence is in the information contained in the source and we can retrieve it by asking relevant questions.

What do we learn of Trim from the plaque? Why was the plaque created?

These questions can be answered from the inscription.

Trim is a cat that travelled the world and circumnavigated Australia. He was an affectionate friend and a delight and pleasure to his fellow travellers. Matthew Flinders wrote the plaque in memory of his cat. The North Shore Historical Society donated the memorial.

Why was Trim part of these voyages? Who was Matthew Flinders and where and when did he die?

We cannot answer these questions from this source. We need either to change the question or find another source of information such as further research at the NSW State Library.

So, some sources contain useful information but often not all of the evidence that is needed by the historian. So …

A source is not the same as evidence. A source becomes evidence if it is used to answer a question on the past. It may be evidence for one aspect of history but not for another.

Primary v Secondary Sources

Sources are broadly categorised as either primary or secondary sources.

Primary Sources are those produced at the time of the event or period under investigation, such as

personal sources such as letters, diaries, personal narratives, photographs (after 1850s), memoirs.

official sources such as newspapers, government publications and archives, speeches, birth and death certificates, shipping lists, court records, council records, maps.

artefacts such as grave-stones, buildings, war memorials, plaques, medals, coins, tools, household implements.

To familiarise yourself with the Library’s website, choose an example for each of the above categories of primary sources in the collection that you may use with your class.

Secondary sources are those sources produced after the period or event under investigation. They may include histories written many years after an event, later newspaper accounts, biographies, documentaries, political commentaries and websites. Secondary sources may provide an overview of an event or issue, a different perspective or opinion of an event, access to statistics, photographs, collections of sources, maps and provide the latest research and scholarship on a particular historical subject.

Interrogating Primary Sources

Historians need to interrogate primary sources to determine their authenticity and whether they will be useful for their particular research topic.

Questioning a primary source:

- is it really a primary source? Is it authentic?

- who wrote/drew/made it?

- when was it written/made?

- where was it found? When and by whom?

- why was it written/made? Who was its intended audience?

- how reliable is it? What sources were used to write it?

- what else was found with it? Can we establish its provenance?

- does it provide any evidence for my particular topic?

Photographs require some specific questions:

Questioning a photograph:

- who took the photo?

- where was it found?

- why was it taken?

- where was it published?

- what is its date? Location?

- does it have a caption? What is it?

- what is written about it?

- was it posed?

- does it provide any evidence for my topic?

If we know very little about a photograph, it will be difficult to use it as a reliable source. We need to know its origin or provenance. Photos can also provide much information about objects, people or place in the background.

Using the Library’s website, choose at least one photograph from the collection that would be useful for your teaching.

Including artefacts/archaeological evidence.

Students need to be introduced to a range of historical sources, including archaeological sources. Archaeologists study the physical remains of the past and together with traditional sources used by historians, a broader understanding of the human past may be gained. Artefacts often provide evidence of the everyday details of life that are rarely recorded in written records. We learn more of the average person from archaeological evidence than from written records, which are usually more concerned about – and written by – educated, wealthy or influential people from the past. Archaeology is critical for gaining an understanding of peoples who did not leave behind written records, such as many convicts who could not read or write.

How historians and archaeologists may work together.

What evidence could we use to learn about early convict life?

Historians:

- Official documents

- Shipping lists

- Tombstone inscriptions

- Diaries

- Paintings from the time

- Personal letters

Archaeologists

- Excavated artefacts from The Rocks

- A convict shoe

- Convict-made pottery or brick

- Leg irons

- Convict tools

- Burials/skeletons

By drawing on both historical and archaeological sources, a more rounded understanding of convict life may be gained.

Questions that may be asked of an artefact:

- what do you think it is?

- what do we already know?

- what don’t we know?

- what can we never know?

- is the artefact original, fake or a facsimile?

- what is it made from?

- what size is it?

- where did it come from?

- when was it made and by whom?

- what was its function?

- how has this artefact been interpreted by others?

- is this type of artefact still in use today? If not, what is used in its place?

- what else was found with it?

- what does it tell about its society?

- why has it survived?

- what is its historical significance?

- is it useful for my research topic?

Using the Library’s website, choose at least one artefact from the collection that would be useful for your teaching.

Interrogating Primary Sources

- is it really a primary source? Is it authentic?

- who wrote/drew/made it?

- when was it written/made?

- where was it found? When and by whom?

- why was it written/made? Who was its intended audience?

- how reliable is it? What sources were used to write it?

- what else was found with it? Can we establish its provenance?

- does it provide any evidence for my particular topic?

Photographs require some specific questions.

Questioning a photograph:

- who took the photo?

- where was it found?

- why was it taken?

- where was it published?

- what is its date? Location?

- does it have a caption? What is it?

- what is written about it?

- was it posed?

- does it provide any evidence for my topic?

If we know very little about a photograph, it will be difficult to use it as a reliable source. We need to know its origin or provenance. Photos can also provide much information about objects, people or place in the background.

Using the Library’s website, choose at least one photograph from the collection that would be useful for your teaching.

Students need to be introduced to a range of historical sources, including archaeological sources. Archaeologists study the physical remains of the past and together with traditional sources used by historians, a broader understanding of the human past may be gained. Artefacts often provide evidence of the everyday details of life that are rarely recorded in written records. We learn more of the average person from archaeological evidence than from written records, which are usually more concerned about – and written by – educated, wealthy or influential people from the past. Archaeology is critical for gaining an understanding of peoples who did not leave behind written records, such as many convicts who could not read or write.

What evidence could we use to learn about early convict life?

Historians:

- Official documents

- Shipping lists

- Tombstone inscriptions

- Diaries

- Paintings from the time

- Personal letters

Archaeologists

- Excavated artefacts from The Rocks

- A convict shoe

- Convict-made pottery or brick

- Leg irons

- Convict tools

- Burials/skeletons

By drawing on both historical and archaeological sources, a more rounded understanding of convict life may be gained.

- what do you think it is?

- what do we already know?

- what don’t we know?

- what can we never know?

- is the artefact original, fake or a facsimile?

- what is it made from?

- what size is it?

- where did it come from?

- when was it made and by whom?

- what was its function?

- how has this artefact been interpreted by others?

- is this type of artefact still in use today? If not, what is used in its place?

- what else was found with it?

- what does it tell about its society?

- why has it survived?

- what is its historical significance?

- is it useful for my research topic?

Using the Library’s website, choose at least one artefact from the collection that would be useful for your teaching.

Interrogating Secondary Sources

- who wrote it?

- when was it written?

- what sources were used to write it?

- are these sources reliable?

- why was it written?

- what has been omitted?

- who was the intended audience?

- have emotive phrases or words been used?

- if so, how does this influence its meaning?

- what perspectives are represented?

- has the writer any reason to be biased?

Select a secondary source that may be appropriate for the teaching of your topic and analyse its usefulness.

How have sources survived?

Sources generally survive because someone wished to keep them, or they survived by chance. Sources that have been kept on purpose may range from personal or family items that are deemed valuable (family heirlooms, grandmother’s birth certificate, old family photographs, grandfather’s war medals) or official sources kept in the NSW State Library, museums, the National Archives or the Australian War Memorial.

Sources that survive by chance could include forgotten items in family attics, old newspapers found under linoleum floors or artifacts recovered unexpectantly in the garden or in an archaeological dig.

Some historical sources may even have been deliberately destroyed.

As teachers, we need to understand the nature of historical method to better adapt our approaches to suit individual classes. It is unlikely that we would work through these source-related issues at one time with students. It would be better to deal with them in an integrated way using a variety of materials or through an integrated approach throughout the year.

Research the Library’s collection and choose at least one source that may have survived because someone thought it valuable or personally important and a source that survived by chance or by accident.