That was the puzzle facing the State Library of NSW in 1982. The plate was one three giant glass plates created by Charles Bayliss for Bernard Holtermann in 1875.

It was part of a hoard of 3500 glass plate negatives discovered in a garden shed in Chatswood in 1951.

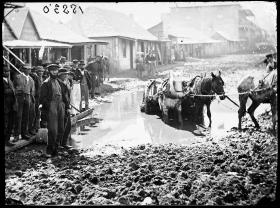

The find proved to be the most important photographic documentation of life during the Australian gold rush; a unique record of a generation experiencing an era of opportunity.

Almost 35 years ago, one of the giant glass negatives shattered. Attempts were made to repair the plate but no satisfactory solution was discovered.

It was boxed and put into storage. The question of how to recover it remained unanswered until now.

At the 18th Triennial Conference of the International Council of Museums - Committee for Conservation, in Copenhagen on 4-8 September 2017, a paper will be presented which explores the collaborative efforts to preserve, reassemble, recapture and rehouse the artefact.

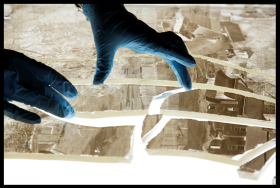

From physical rebuilding to best practice digital imaging, the reconstruction of the Holtermann plate involved four conservators and the expertise of our Digitisation and Imaging Team.

The plate was assembled into six sections on 15mm acrylic trays, thick enough to support the glass without bowing or distorting the image, and digitised using a custom built light box, lighting the glass from below.

For capture our Digitisation and Imaging team used a 50 mega-pixel Hasselblad camera, and to maximise resolution, each of the six sections was digitised in overlapping frames, then stitched together.

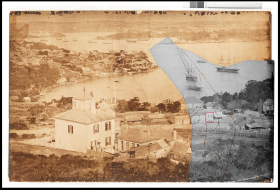

The Library also collaborated with University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Big Global Data Technologies Centre. Using artificial intelligence mapping techniques, images from a large contact print taken before the plate was broken, replaced the areas of the negative that had been shattered.

The resulting image is a miraculous restoration of what was thought to be lost.

The painstaking process, which took incredible precision, will be described in the upcoming edition of SL magazine.

Read more about the Holtermann Collection

Thanks to Anna Brooks, Lang Ngo, Nichola Parshall, Catherine Thomson, Collection Care, Bruce York, Joy Lai, Matthew Burgess and the Digitisation and Imaging Team.