As I read through the words and phrases in Australian English that date back to World War I, I am struck by two clusters of words. The first reflects the fact that any sphere of activity has not only its official names, but also its unofficial names. We tend to bond over words that are not imposed from above but spring directly from experience.

The second relates to humour, ranging from the cheerful domestic kind to bordering-on-hysterical. Black humour can be an attempt to prove, to ourselves and others, that we can deal with unspeakable horror.

The group of Australians and New Zealanders that joined the expeditionary force on the Gallipoli Peninsula was initially called the Australasian Army Corps. After New Zealanders objected to the colonial catch-all of ‘Australasia’, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps became the official name, quickly shortened to ANZAC.

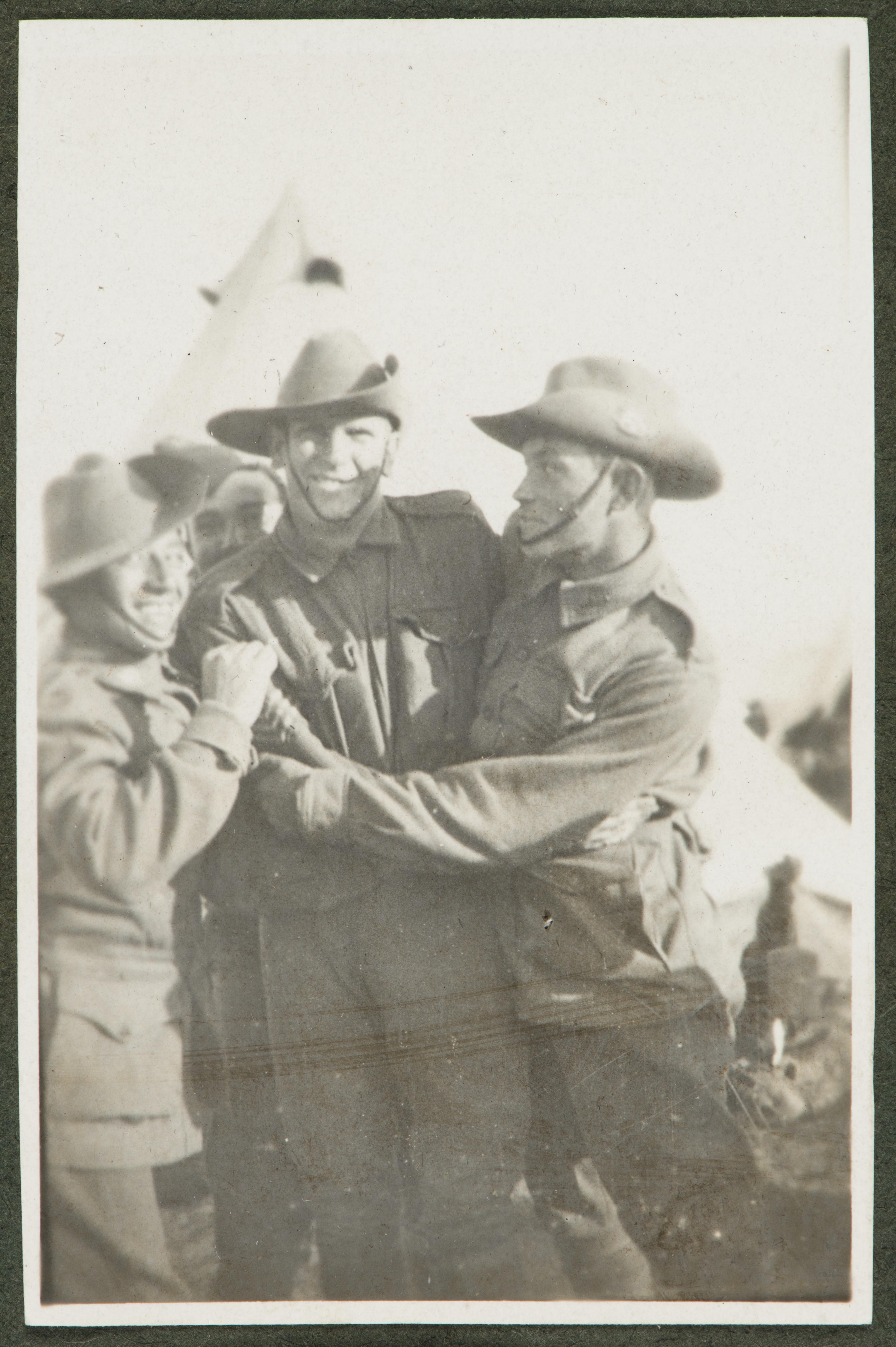

But their informal name was the Diggers. The first specialised use of digger in Australian English dates back to the 1850s gold rush in Victoria. This use carried on through the century right up to the goldfields rush in WA in the 1890s.

In New Zealand a digger might be a miner in the goldfields, or someone digging for kauri gum, a fossilised resin used for jewellery.

When Australian and New Zealand soldiers went to World War I in France and were introduced to trench warfare, the term digger perhaps came more naturally than the British sapper. While it was the soldiers at the front line digging the trenches who earned this name, it began to encompass Australian and New Zealand soldiers of any rank and was used as a form of greeting. Prime Minister Billy Hughes was affectionately nicknamed ‘the Little Digger’ by the Australian troops he visited in France.

The diggers referred to the Turkish soldiers as Abdul, a common first name in Turkey. Following a similar logic, the Turks called the Anzacs Johnnies and themselves Mehmets. As Mustafa Kelmet Atatürk wrote in 1934, ‘There is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours.’

A discussion of significant locations during this period must begin with Gallipoli. The irony of ironies is that the name meant ‘beautiful city’ from the Ancient Greek kallos ‘beautiful’ and polis ‘city’. The other landmarks of the region are so well known that we can pass on to the unofficial naming that was part of the job of the soldier.

Locations needed to be identified in fine detail and the colloquial names are engraved by terrible experience.

Baby 700 the smaller of two adjacent hills, estimated to be about 700 ft high

Lone Pine a site above Anzac Cove where the Turks cut down all the pine trees except one

The Nek a ridge of land on the Gallipoli peninsula Then there were the names for weapons:

Beachy Bill a Turkish artillery battery concentrated on the beaches of Anzac Cove

Big Bertha a type of howitzer used by the Germans and named after Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (1886–1957), proprietor of the German industrial company Krupp

flaming onions a form of incendiary used by German forces to illuminate and set fire to a target

flying pig a heavy trench-mortar shell, named either for its large size and slow descent, the squeal it made flying through the air, or both

gezumpher a large artillery shell

Lazy Lizz a heavy long-distance shell which made a droning sound as it passed

Minnie a German trench-mortar bomb, from the name Minenwerfer

mouth organ a Stokes shell, from the sound made by the air passing through the holes around the base of the shell as it was rising

pipsqueak a small, usually high-velocity, shell fired from a field gun

plum pudding a spherical iron shell filled with explosive and fired from a trench mortar

And the soldier's life:

lie-out possie the position taken by troops when assembled in battle formation before an attack

mug-gunner a Lewis machine gunner

over the top over the top of a parapet, as in charging the enemy

slushy a mess orderly

spook an army signaller, especially a wireless operator

up the line in action

With the war’s inevitable toll on a soldier’s health, the Aussie was the equivalent of the British Blighty – that is, the wound that was serious enough to have you packed off home.

Humour also comes through in the various uses of king meaning ‘expert’, one of which was iodine king for a regimental medical officer. The iodine lancers were members of the Australian Army Nursing Service, a nickname that neatly captured the general use of iodine for treatment and the prevalence of boils needing to be lanced. (The kiwi king was the soldier who polished his boots and leather carefully, from the Kiwi boot polish brand.)

The first target in the army, as in any institution, was the food. There was the official iron rations, but also the joke Anzac wafer (modelled on vanilla wafer), described in WH Downing’s 1919 collection Diggers Dialects as a hard biscuit, ‘one of the most durable materials used in the war’. Anzac stew was made with an urn of hot water and one bacon rind. Flybog was the name for jam, since flies were the scourge of Gallipoli and got into anything greasy or sticky. Axle-grease was the word for butter. And a shell burst was known as a cream puff.

Humour comes also in borrowing words and phrases from the languages with which the ‘six-bob- a-day’ tourists (from the soldiers’ daily pay rate of six shillings) have suddenly come into contact. From French came such expressions as alley ‘to go’ from allez, compree ‘understand’ from compris, plonk ‘cheap wine’ from vin blanc, san fairy Ann ‘no matter’ from ça ne fait rien, and toot-sweet ‘immediately’ from tout de suite. From Arabic there was bint ‘a woman’, imshi ‘to go away’, magnoon ‘crazy, idiotic’, maleesh ‘no matter’, and the Wazza from Haret al Wassir ‘the red-light district in Cairo’.

Even heroes and villains can be taken not so seriously in war. The cold footer and slacker are basic enough terms but deep thinker, meaning ‘a person who enlisted late in the course of the war’, has that touch of amused mockery. Knut, meaning ‘a self- important person’, is definitely a joke. It is thought to have come from the popular music-hall song Gilbert the Filbert, the Colonel of the Knuts (1914) in which knut is a jocular variant of nut. This was parodied and used as a marching song.

Susan Butler is the editor of the Macquarie Dictionary.

Digger Dialects can be accessed through the Library’s catalogue.