In favour of bad art

Let’s raise a glass to what some would call ‘bad art’.

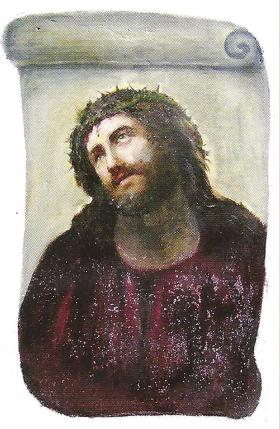

The sages, poets and thinkers through the ages are all aligned in adoration of mastery in artistry. I’ve no argument with them: but I’d like to humbly raise a glass and offer a few words in defence of bad art. I’m not talking about the over-eager, under-skilled nun botching a fresco kind of bad art: I’m singing the praises of the bad art that makes good art possible, and socially focused art that looks nothing like the stuff you see on gallery walls.

For starters, you don’t get good art without the bad: British artist David Shrigley OBE once told me he threw out more than 90 per cent of the work he made. All those scrunched up attempts on the studio floor are an essential part of the process. Often, artists produce prolifically, take risks and try new things, rethink, rework, and then cut back critically. As viewers we only see the distillation of an artist’s practice, but to get to the good stuff, they need to be able to take risks, make mistakes and, yes, even to make bad art. The edit is often where a discerning eye comes in to sort through the chaff and find the wheat, and curators and gallerists can play a big role in helping artists make the cut.

Secondly, art that’s experimental and of the moment today may end up looking less than fresh — even bad — a few years later.

Looking at the history of electronic art (that blurry catch-all genre that was called ‘new media’ for much longer than it was new), I find myself less than impressed. Work that was once considered cutting edge is now outdated and, well, bad. From the perspective of 2021 it falls into the ‘my kid could do that in 20 minutes on Minecraft’ basket, and both the technical chops and intellectual pursuit can seem basic and clumsy.

But we’ve got to cut those video and tech art pioneers some slack: being the avant-garde means you’re out in front clearing the path with DIY, pushing technology to work in ways previously unimaginable; looking backwards, we lose the context. The grandfather of tech art, Nam June Paik, was visionary in his day, and yet his assemblages and videos increasingly look more like ancient relics than totems of the future. The transgressive digital art of Hito Steyerl pushed boundaries, but her explorations of digital identity and privacy in the 2010s may be passé sooner than we’d think.

The net art experiments of today may be destined for the same fate: there’s some extraordinarily creative stuff happening on TikTok right now, but it probably won’t age well. The tools of tech art practice have evolved much faster in the last 50 years than the oils available to the classical masters may have changed in 500. So, as we assess our more recent art history, we’re going to be looking back onto some embarrassing examples from the 1990s and early 2000s of what looks like bad art. But we need that bad art: experimentation and forays into the unknown are the only way to break new ground.

My third argument in favour of bad art is one that asks us to value the process over the outcome. The art I really love isn’t as fixated on aesthetic excellence as it is on the experience for participants or on social change: it really is about the journey rather than the destination. The work that inspires me most is participatory, collaborative, socially focused practice — it takes a lot of different forms, from community cultural development to social sculpture. It’s art that prioritises the growth and connections made by the participants, and challenges and changes the status quo, rather than necessarily being focused on expertise or aesthetic qualities.This is work that has bigger goals than beauty, though the outcomes can be beautiful. If you value technical mastery or aesthetics, you might think it’s bad art, but for me, it does what great art should do: it transforms the way you see the world, it reveals stories and unlocks possibilities.

Sometimes this work can look like architectural practice, such as in the case of the UK’s Assemble Studio, which was awarded the Turner Prize for its work supporting the community of Liverpool’s Granby Four Streets neighbourhood in reclaiming homes left derelict by bad policy. It can look like property development, as in the work of US artist Theaster Gates who has restored creative infrastructure on the South Side of Chicago. Gates trained as an urban planner and practised as a ceramicist and sculptor before he decided to mould neighbourhoods. He trains people to rebuild their places, using music and creativity to heal and to show what’s possible when generous civic spaces are given back to communities who’ve had them torn away. In Australia, Big hArt have combined art and social justice in transformative projects that span years, embedded deep in communities, but often their work looks more like legal advocacy, gardening, theatre or education.

For me, there’s much to admire in the unconventional, the experimental and the ambitious work that some might not see as art, or consider to be bad art. And remember that botched holy fresco? When Sister Giménez’s clumsy repainting of Ecce Homo became a meme, it also turned into a tourist attraction, drawing thousands of visitors to her town of Borja in Spain. Bad art was the wellspring of a river of tourist dollars for the village: proving beauty and talent aren’t the only paths to art glory.

Jess Scully is Deputy Lord Mayor of Sydney. She is a Councillor, a public art curator and writer. Her first book Glimpses of Utopia was published in 2020.

This story appears in Openbook Autumn 2021.