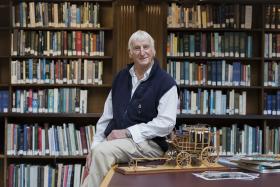

Model maker

Peter urgently needed plans for a timber model he was working on. But it was May 2020, and the Library was closed.

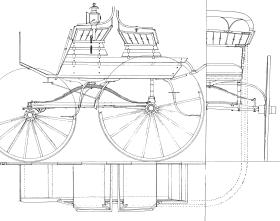

Although the Library couldn’t accept visitors during last year’s lockdown, staff were on hand to help. When Peter phoned the Library to try to find plans for a buggy wagon, he was put through to librarian Kathi Spinks. Kathi located a copy of Michael Stringer’s Australian Horse Drawn Vehicles, photocopied several pages, and popped them in the mail. ‘Thanks for your help and going beyond the call of duty,’ wrote Peter in a handwritten thank you letter. ‘I sing the praises of the State and Mitchell Library.’

Peter set up a workshop in the back bedroom of this house and began work on the Cutty Sark, a fast and famous clipper. He softened the wooden planks with boiling water and looked at rigging for hours on the docks at Port Macquarie and Darling Harbour before attempting to make it himself. He estimates that the finished model took him 500 hours. He went on to build 14 more models of working ships and boats before turning his attention to horse drawn sulkies, coaches and wagons. Peter is not connected to the internet (‘I’m still on smoke signals, my dear!’), so when plans are not available from museums or companies, he uses the Library to research and plot his course.

‘Making models is a meditation,’ he says. He sets himself a daily task and doesn’t stop until he has achieved it. ‘When you make something with your hands, you lose yourself.’ But Peter’s descriptions of his experiences in the Library suggest that the activity has also been about finding himself.

Peter grew up in Sydney’s Bankstown during the Second World War and the early post-war years. He describes ‘a tough childhood’ in which clothes coupons were the only way to put school shoes on his feet. ‘We used to say if you had toilet paper, a car and a phone, you were rich!’

An introverted kid, Peter’s pleasures were the weekends and holidays spent in his mother’s tarred paper cabin at Bonnie Vale in the Royal National Park. There he swam, fished and made things. He joined Bankstown Library as a 12-year-old, borrowing books to acquire all sorts of knowledge for tinkering. His mother had a unique way of describing her son’s compulsive curiosity: ‘You’d like to know the ins and outs of a duck’s bum!’

Fifteen years ago, that curiosity brought him through the doors of the State Library. ‘I was passing by one day and decided to pop my head through those magnificent doors.’ Peter recalls seeing the book-lined galleries of the Mitchell Library Reading Room and thinking, ‘Look at all this knowledge in here. It’s almost overwhelming.’ He quickly overcame his awe, and has been ‘haunting the place ever since’. ‘I left school at 14,’ he says. ‘I always want to be a better person, to educate myself all the time.’

Peter did extensive research on life during the Great Depression. He was driven by ‘an interest in people, how people fared during those times, how they were treated — swagmen, Indigenous Australians, images of poverty. The poor will always be with you.’

At 82, Peter begins each new day with a swim at one of the beaches or ocean pools of northern Sydney. And he meditates. Recently, he’s been back in the Library putting together plans for a ‘drop front phaeton’ using three different books in the Mitchell collection. He explains that a phaeton is an open carriage of the early nineteenth century, another working vehicle forgotten by time.

While he’s sharing definitions, he smiles warmly and adds, ‘Do you know the word apricate? It means to bask in the warmth of the sun.’ Every now and then Peter allows himself a moment to bask in the satisfaction of looking at his models and all that they hold of the past. ‘They are like my family. I built them myself.’

Mathilde de Hauteclocque

Library assistant

This story appears in Openbook Autumn 2021.