Our twenty-first century idea of ‘wellness’ may be hard to define, but many of us aspire to it, or are told we should. Along with a focus on physical health — maintaining a healthy diet, exercising regularly, participating in the occasional dry July, consuming less red meat or doing a sugar or caffeine detox — wellness encompasses our mental and spiritual health. Google the term ‘wellness’ and you will find multitudes of studies and graphs and much guidance about how to attain personal wellness. In short, how to strike a balance between physical health and emotional, intellectual, financial, social and spiritual fulfilment.

These measures don’t come cheap, but all seek the same outcome: finding ways to live a balanced life. A healthy life. Achieving a work–life balance is living the dream, isn’t it? A yoga class in the morning before work, a conference call before a delicious vegetarian lunch, team meetings in the afternoon before school pickup, joyful family time and somehow, in the midst of all this, learning an Instagrammable new hobby. Living your best life.

But a balanced life is not a modern invention.

For centuries, the idea of a healthy body meant a balanced body. Ancient Greco-Roman ideas about the four humours and the balanced body prevailed over many centuries. They arrived in Europe during the Middle Ages and, thanks to the printing press, this knowledge flourished. Herbals and medical books were among the first books published and were widely circulated. Medical knowledge at the time was a complicated mix that blended lingering paganism with local knowledge, ancient folk charms and remedies, superstitions, and a powerful belief in God and all things divine. Humoural theory was upheld in medical writing and practice until well into the nineteenth century.

When visitors to the Library’s Kill or Cure exhibition step into a number of ‘treatment rooms’, they will glimpse the powerful and enduring ideas of the four humours and the balanced body.

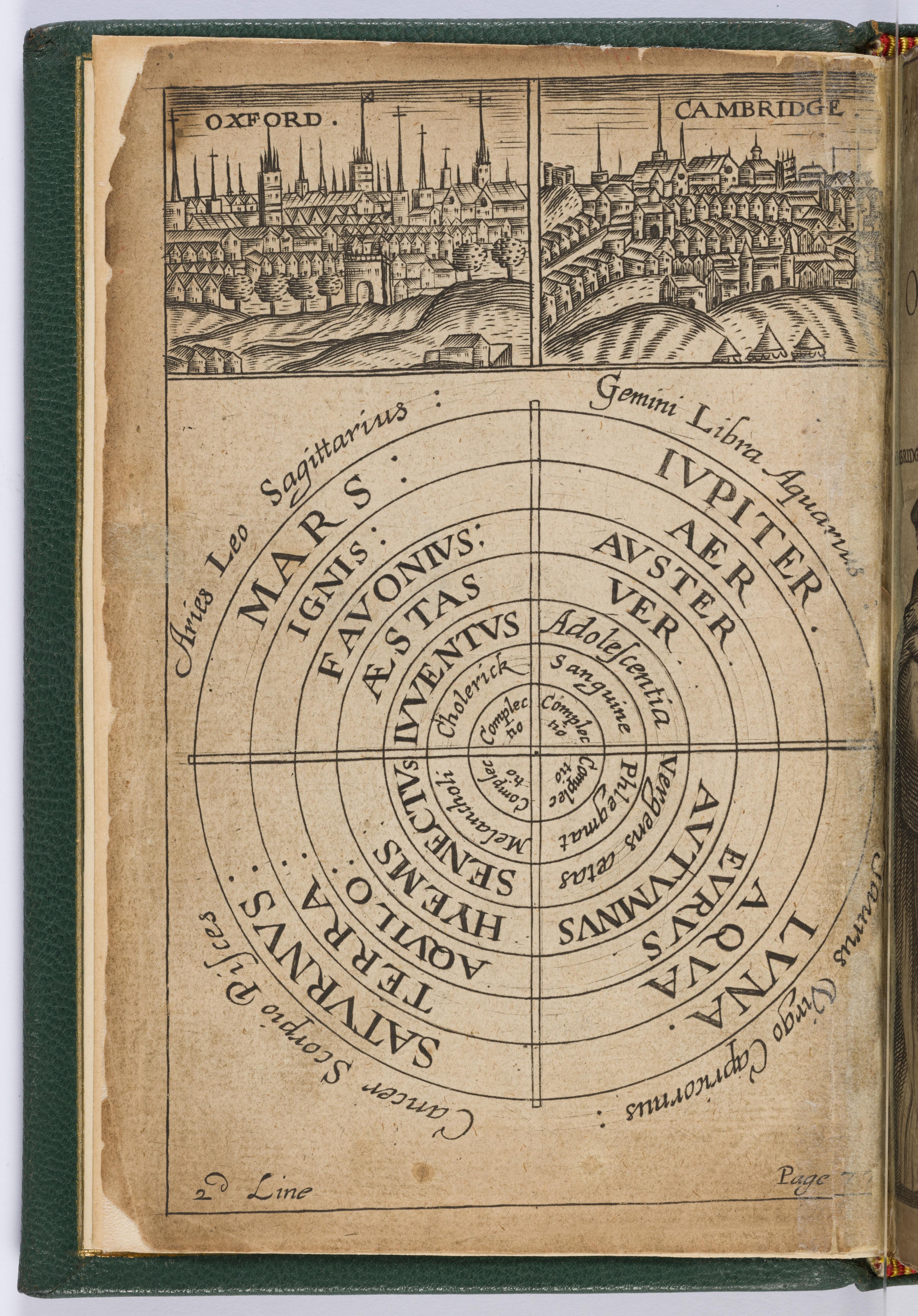

The ‘humours’ were four liquids understood to flow within the body in equal measure: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Each of the four humors was linked with two of four fundamental qualities: hot, cold, wet and dry, and one of four elements: air, fire, earth or water. These, in turn, were linked to a season, an organ in the body and an astrological sign, which influenced not only the physical body, but an individual’s temperament as well.

When the body became sick or diseased, it meant there was an excess of one humour, or a deterioration or imbalance of any of the humours. The solution lay in ridding the body of the excess bad humour, and thus restoring it to balance. This was achieved through various treatments, either an enema, vomiting or bloodletting.

These imbalances could also be caused, it was thought, by various alignments of the planets and stars, or by bad air, or miasmas, that prompted epidemics such as smallpox, plague, malarial fevers and intestinal infections, spread from person to person. Early modern ideas around infection control were not entirely misguided:

‘You shall have a care that your houses be kept clean and sweet, not suffering any foule and filthy clothes or stinking things to remain …’

Western medicine’s main emphasis at this time was on prevention, particularly through building a strong body and following a daily health regimen. Moderation in food and drink, a restful night’s sleep, and exercise were all recommended to keep the body in balance and, therefore, in health.

A helpful seventeenth-century guide, Everyman His Own Doctor, reminds us to do ‘everything in moderation’, good advice that still stands today:

considering the great damage that comes upon most people daily by not knowing, or not regarding their own constitutions of body; whereby they neglect the precious Jewel of Health, and so by ignorance do live negligently, and do eat and drink they care not what … thinking it cannot be bad for them, so it please the palate — but thereby many dig their graves with their teeth.

This warning not to ‘dig your grave with your teeth’ might not be found on a modern public health leaflet, yet its meaning rings true for us: don’t overindulge. More vegetables, less ale.

The same guide highly recommends:

Exercise doth increase health and strength, also it moves and agitates the spirits, from whence the heart is made strong and can resist external injuries … those bodies that live idly, are soft and tender, and unfit to perform labours of every kind as dancing, running, playing at ball, gesture of body, riding, swimming, walking and all others.

The seventeenth-century person was encouraged to generate a ‘naturall sweat’, to open the pores, clean the blood and comfort the spirits. We know today that a good way to deal with stress and anxiety is to exercise, because it releases endorphins and enhances our mood.

A further benefit of bathing or ‘sweating’ was that the practice removed superfluous humours from the body. Inducing sweat in what we would call saunas or steam rooms, or therapeutic bathing, immersing the patient in water, or washing various body parts in water, was seen to be beneficial. The word ‘spa’, a common site for ‘wellness’ treatments and therapies today, comes from this idea of ‘taking the waters’.

The lunar cycle was believed to govern the course of acute illnesses, while the solar cycle governed the course of chronic illnesses. In late-medieval European society, the planets were understood to influence almost every aspect of life, from the wars, famines and epidemics that affected masses of people to individual or familial relationships, health and success. Almanacs from the year 1684, for example, gave dire warnings that ‘The effects of these eclipses will presage sickness and such diseases as will prove contagious, and for the most part, mortal.’

To understand the course of an illness, the physician had to study the position of the moon and sun in relation to the zodiac at the onset of illness. Interpreting the astrological influences at that moment, and knowing the future movements of the stars, meant he (it was always a he) could predict how the illness would progress.

The heavens were seen to hold answers not available on Earth:

now a cruel condition (about which I have a dread of speaking), also a horrible and spotting … and a death-bringing disease has been sent by France … the damage grows everywhere; even on our bodies one sees much disease … Many wish to die as soon as possible, so badly does the inner pus or the rotting blood hurt them. It burns, punches, and pricks them, inflames, tortures and itches with all kinds of pains and torments them. SINCE I want to get to the bottom of this terrible and cruel sickness and since no doctor of medicine can discover the causes of this illness, I turn to the astronomers and to the teachers of the art of the stars.

Ein hübscher Tractat von dem Ursprung des Bösen Franzos, 1496

Much medical astrology was concerned with lunar prognostication. For physicians, phases of the moon and the precise position of the moon in the zodiac could determine the right time for bloodletting. However, the actual bloodletting was carried out by master surgeons or barber surgeons.

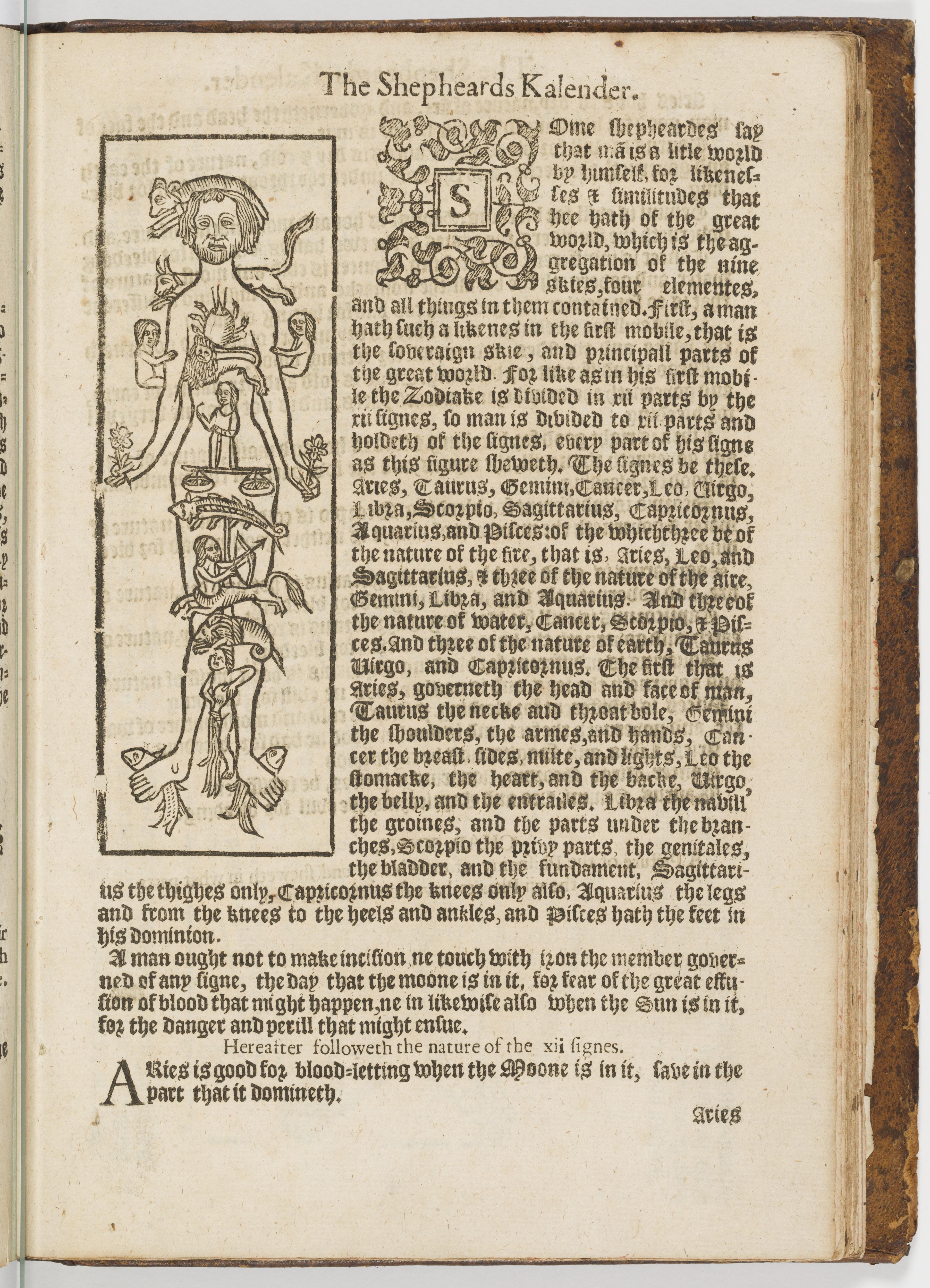

The image of the bloodletting man was a common illustration in early modern medical books. A common image depicts a naked man, with labels indicating which veins are to be opened for the relief of a variety of medical conditions:

when the body is filled with naughty and superfluous humours, it is convenient to draw blood (if the heavens consent) … As for the pestilence ... the pleurisy, a continual headache, a hot burning fever or any extreme pain … a vein is speedily to be opened.

Almanac, 1640

The astrological diagram known as the Zodiac Man had been in use in Europe since the eleventh century. It illustrated the relationship between the universe and the human body, indicating the influence of each zodiac sign over a part of the body, or a specific organ. This image generally included the twelve astrological signs arranged around the figure; if the sign governing a particular part of the body was affected by a malevolent planet or bad aspect, that arm or leg, heart or spleen would become ill.

Take notice that the womb of a woman is under Scorpio; for under Virgo it cannot be, because Virgo is a barren sign; Scorpio is a fruitful sign because it rules the womb: and Cancer and Pisces are fruitful because they are of the same triplicity.

A Directory for Midwives, Nicholas Culpeper, 1762

Medicines were not capsules in foil blister packs, but tinctures, unguents, poultices, potions and tonics. From ancient times, across human societies, botanicals of all kinds were recognised for their healing qualities, so the raw materials were herbs, plants, roots and trees. Many remain active ingredients in various medications today.

Learn the high and marvellous virtue of herbs know how inestimable a preservative to the health of man God hath provided growing every day at our hand Use the effects with reverence and give thanks to thy maker celestial.

The vertuose boke of distyllacyon, by Hieronymus Brunschwig, 1527

Elise Edmonds is a senior curator.

Kill or Cure: A Taste of Medicine is on display at the Library until Sunday 22 January 2023.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2022.