Cressida Campbell selects a cockatoo feather from a bowl of natural objects in her Bronte studio, and brushes it across the top of my hand. The artist is demonstrating the strange sensation she had on her own hand that day in August 2020, the day her life changed.

Puzzled but not overly concerned, Campbell wasn’t to know it was the first sign of something badly amiss. After that, a martini glass slipped through her hand and smashed on the floor. Then her hand began to shake. Campbell ended up in St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, where doctors ordered the first of an eventual 18 MRI scans. She would be in St Vincent’s for five weeks, her life hanging in the balance. ‘Quite honestly, I nearly died,’ Campbell says.

On the day Openbook visits, she is working in her studio on one of the final paintings for her solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia. Simply titled Cressida Campbell, the exhibition will run from 24 September 2022 until 29 January 2023.

Given her dexterity as she touches tiny strokes of paint onto her work, it’s hard to imagine that the artist’s entire right side was paralysed less than two years ago. Doctors were uncertain whether she would be able to regain the fine motor skills so crucial for her art. They even thought she might never walk again.

Campbell recalls the day one of her doctors asked her to draw a star so he could see if she was progressing. The best she could manage was a shaky scrawl. ‘That was the time I burst into tears and said, “do you think I’ll ever recover?” And of course, they didn’t know. It was the most traumatic thing,’ Campbell says.

Miraculously, after the discovery of a brain abscess and two brain operations, followed by a period of rehabilitation, Campbell is well. She is working as hard as ever at her hulking French easel that she dryly likens to a guillotine. ‘I pretty much work seven days a week, which I like,’ she says.

On the professional front there’s the National Gallery of Australia exhibition which has been curated by Dr Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax, the gallery’s curator of Australian prints and drawings. Campbell also has a show at Philip Bacon Galleries in Brisbane from 26 July.

On the personal front, Campbell is getting married. When we spoke, she was preparing for a 30 April wedding to fine art and photographic printer Warren Macris. Among the top photographers and artists he works with at his Mascot business are stellar practitioners like Greg Weight, Tamara Dean, Gary Heery, Stephen Dupont and Petrina Hicks. ‘Warren is the most enchanting man,’ Campbell says. ‘Like my father, he’s incredibly modest. Everyone adores Warren.’

Campbell’s father is not just part of her story, he’s part of Sydney’s story. Ross Campbell was a Rhodes Scholar but his fame was not earned through erudition. What people loved were his humorous columns about Campbell family life in the lower north shore suburb of Greenwich. The pieces appeared in the Daily Telegraph, the Sunday Telegraph and the Australian Women’s Weekly.

The youngest of four siblings, Cressida appeared in her father’s columns as Baby Pip. In one of his writings, Baby Pip’s sisters give her some marriage advice printed on a lolly wrapper. In another, Ross Campbell carries Baby Pip on his shoulders through Jenolan Caves. Campbell adored her father, who died when she was 21. She suffered another early loss in 2011 when her husband, the film critic Peter Crayford, died of cancer at 61. She still wears Crayford’s old shirts to paint in.

Campbell and Macris began dating about five years ago. It was during a trip to the Blue Mountains that Macris popped the question. ‘He proposed to me on this precipice. It was a bit like that Caspar David Friedrich painting,’ Campbell says. ‘He was so nervous. He brought out this little black box and there was a moonstone ring in it. It was incredibly touching and I said yes.’

Just days later, Campbell had that feathery feeling on her hand. Her subsequent illness was nightmarish, spelling the possible end of her slow and patient production of seductively beautiful pictures.

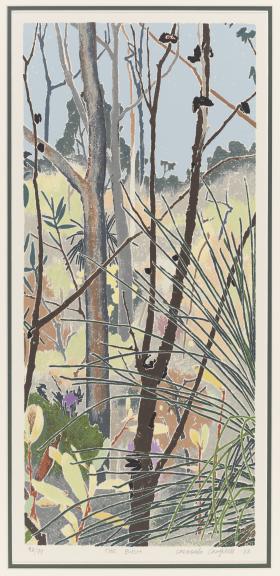

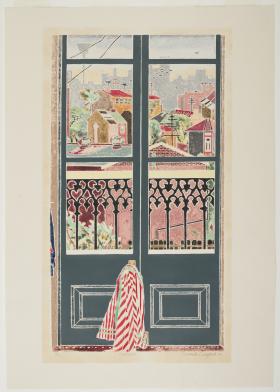

The blocks and prints take months to make. Their crispness and detail must be seen to be believed. While the connection to the Japanese woodblock tradition is obvious, Campbell’s works are very much anchored in contemporary Australia. Her stunning compositions often feature interior scenes with bowls of luxuriant flowers juxtaposed with everyday items found around the home. Less well known, but just as beautiful, are her landscapes.

Campbell’s process is unique in Australia, as far as Noordhuis-Fairfax knows. It dates back to East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School) where Campbell studied in the late 1970s. When Campbell arrived at the Tech, she quickly rejected the style of painting it was teaching.

‘They wanted you to paint with a giant, thick brush and I only use really small brushes,’ Campbell says. ‘They wanted you to paint like Cézanne. As wonderful as Cézanne is, it was totally not my thing and it made me very self-conscious because I was hopeless at it.

I think teachers should encourage whatever the person’s leaning is. As [her great friend, the artist] Margaret Olley used to say, everyone’s got their own handwriting and it will come out.

‘So in the second year instead of doing painting, I did printmaking. They just taught you the actual methods of printmaking. They didn’t say what to do.’

Lecturer Leonard Matkevich devised the bespoke technique for Campbell. ‘Leonard suggested this technique at some point. You know, “why don’t you draw on a woodblock and paint on to it and then we’ll run it through the press?”,’ Noordhuis-Fairfax says. The resulting artworks are positioned between painting and printmaking, with characteristics of both.

The lift of the paper from the block during the printing process lends a mottled texture to the woodblock, while the print itself takes on the wood grain, the carved lines and the paint.

In conventional woodblock printing, a separate block is used for each colour in the composition. The last block used is the ‘key block’, which is covered in black paint to define the main shapes and hold juxtaposed colours in their rightful places without bleeding into each other. Woodblock printing is traditionally done in a press. Campbell, however, always hand-prints her work.

‘Watching her print a work was an amazing experience,’ Noordhuis-Fairfax says. ‘I felt like I was holding my breath for two hours. She didn’t stop moving. It’s a technique where lots of things can still go wrong. It doesn’t matter that she’s been doing it for over 40 years. There is a definite element of risk in the process.’

The catalogue for the National Gallery of Australia exhibition will be the first major publication on Campbell’s work since the handsome and much sought-after tome, The Woodblock Painting of Cressida Campbell. Published in 2008, it was edited by Crayford with an introduction by the late Edmund Capon, former director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The book was published to coincide with Campbell’s survey exhibition at the SH Ervin Gallery on Observatory Hill in Sydney.

Capon wrote: ‘In a world of contemporary art so conditioned by issues, portentous “statements”, egos and the passing foibles of fashion, [Campbell’s] work is a joy to behold in reaffirming, as it does, the opportunity for beauty and intimacy in the most familiar and prosaic of subjects. It is this distillation of the commonplace into timeless and life-sustaining compositions that is the character of her work. Her vocabulary may be disarmingly ordinary but the works live with extraordinary and convincing credibility.’

The National Gallery of Australia exhibition will feature about 100 artworks on loan from institutional and private collectors, arranged in themes such as floral still life, food still life, interiors, local Sydney landscapes, coastal views and so on. The earliest works date back to when Campbell was ten, and the latest are fresh off the easel this year. Some of Campbell’s paints and implements will be on view, and a video has been made of her working in the studio.

She loves British artist Lucian Freud’s early, linear pieces before his canvases began to abound in flesh. Among Australian artists, she likes John Brack and Ian Fairweather.

Of the Japanese ukiyo-e artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, Campbell’s favourite is Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806).

In 1985 Campbell spent several weeks learning woodblock printing at the Yoshida Hanga Academy in Tokyo. It’s tempting to imagine what a formative experience this must have been for the young artist, but Noordhuis-Fairfax points out that Campbell’s technique was already established by then. What she did learn in Tokyo was composition, and how to lead the eye around the picture plane.

‘When you look at Japanese prints you don’t notice yourself doing that. But that’s what they do. They guide you around. And that’s what [Campbell] does in her own work’, Noordhuis-Fairfax says. Campbell says she has a similar natural aesthetic to the Japanese woodblock makers ‘in the way that I do stylised compositions and the pieces are very linear’.

The woodblock on the ‘guillotine’ when I visited was round, rather than square or rectangular. It depicted an elegant composition including, of all things, an iron. ‘I like the idea of putting in an object that most people would think is pretty dreary and making it beautiful,’ the artist says. ‘Also it changes the attitude of what would be a slightly conventional subject to putting something a bit industrial that most people would hide.’

Cressida Campbell certainly isn’t ‘most people’, and her life so far has been extraordinary. It looks a lot like it will continue to be so.

Elizabeth Fortescue is a freelance arts writer.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2022.