Botanical artist Janet Hauser contacted the State Library in 2018 and offered her series of drawings based on the lost plant specimens of Edmund Kennedy’s ill-fated 1848 expedition. The curators were intrigued, particularly given the library’s collection strengths related to early European exploration in Australia and botanical art. The original specimens, collected by botanist William Carron throughout the expedition, were left behind during his dramatic rescue.

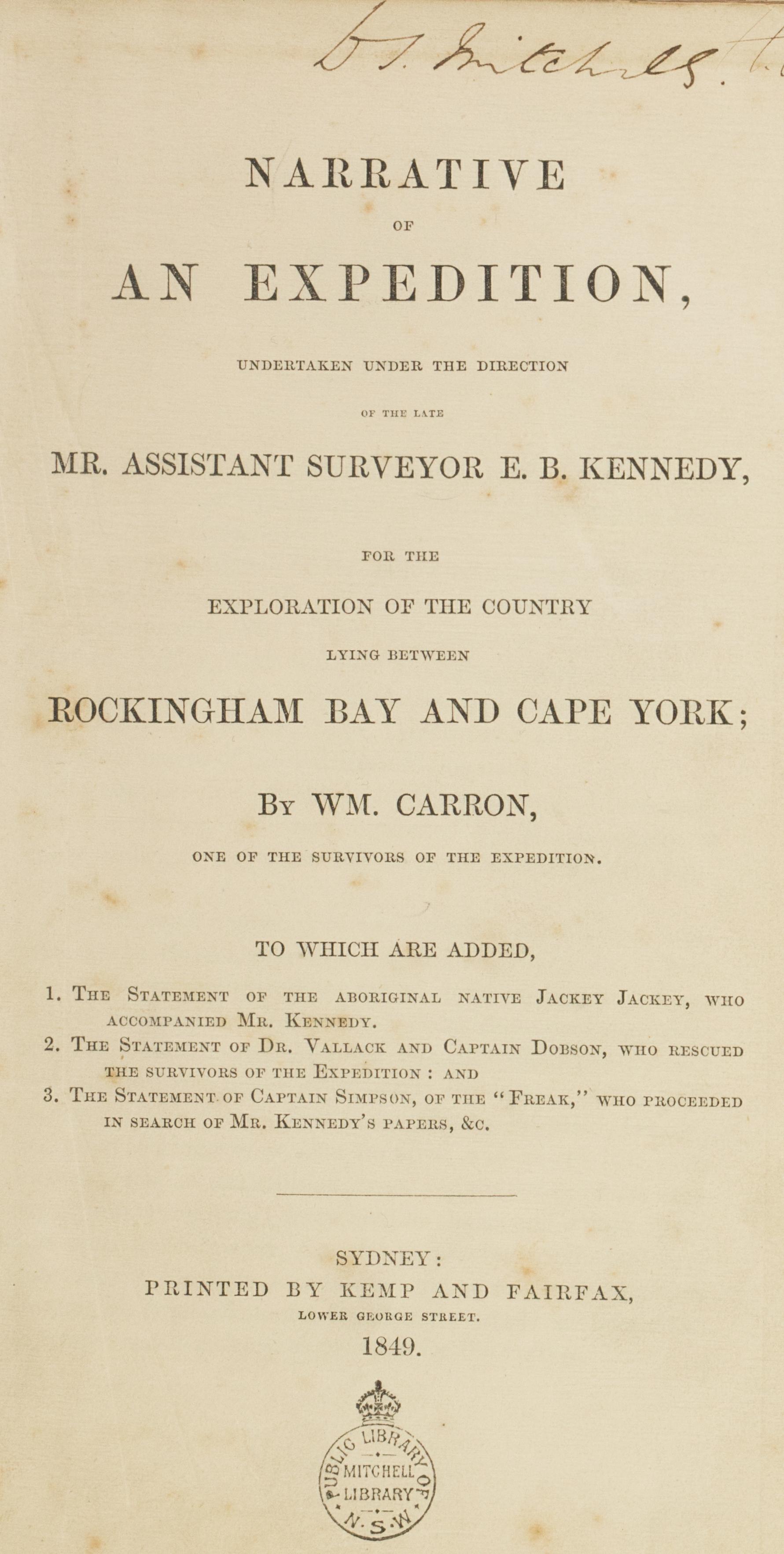

Like most people, Hauser had not heard of Carron when a friend suggested him as the inspiration for her next project. She read his account of the expedition, published in 1849, which provided insights into the immense hardships experienced by the party as well as records of the plants he saw.

‘It became clear to me,’ Hauser recalls, ‘that Carron’s dedication to botany, his life’s work, deserved to be more widely known about and recognised and I hoped, by painting his discoveries, my project would in a small way bring his name to light.’

As a young child Hauser received a gift of paints and brushes from her mother, which set in motion a long-lasting love of art and plants. Hauser says she always remembered places by the plants that grew there. Her first job as a professional botanical artist, in the 1970s, saw her illustrating noxious weed species for the Queensland Lands Department. Since then she has worked on several historical botanical projects, as well as illustrating books, and writing and illustrating a concise study of heritage plants of Queensland’s Scenic Rim region, Grandfather Grew Mangel-Wurzels.

Having read Carron’s account and unpublished biography by Lionel A Gilbert from 1950, Hauser resolved to retrace the botanist’s historic footsteps from the time when Queensland was part of New South Wales. To begin she spent two years researching his plants and the expedition route.

Growing on the beach was a species of portulaca, a quantity of the young shoots of which I collected, and we partook of them. There were many other interesting plants growing about but the afternoon turning wet, I left their examination over till finer weather.

— W Carron, 25 May 1848, from Carron’s narrative for accompanying illustrations by Janet Hauser Sea Purslane Sesuvium portulacastrum & Coastal Jack Bean Canavalia rosea

Then in July 2012 she embarked on a seven-week trip to the Cape York Peninsula, setting off from Kennedy’s first campsite, now Kennedy Bay, South Mission Beach. ‘To be actually standing in the same place and imagine it just as Carron described,’ says Hauser, ‘added another dimension to my understanding of the hardships endured by Kennedy’s men.’

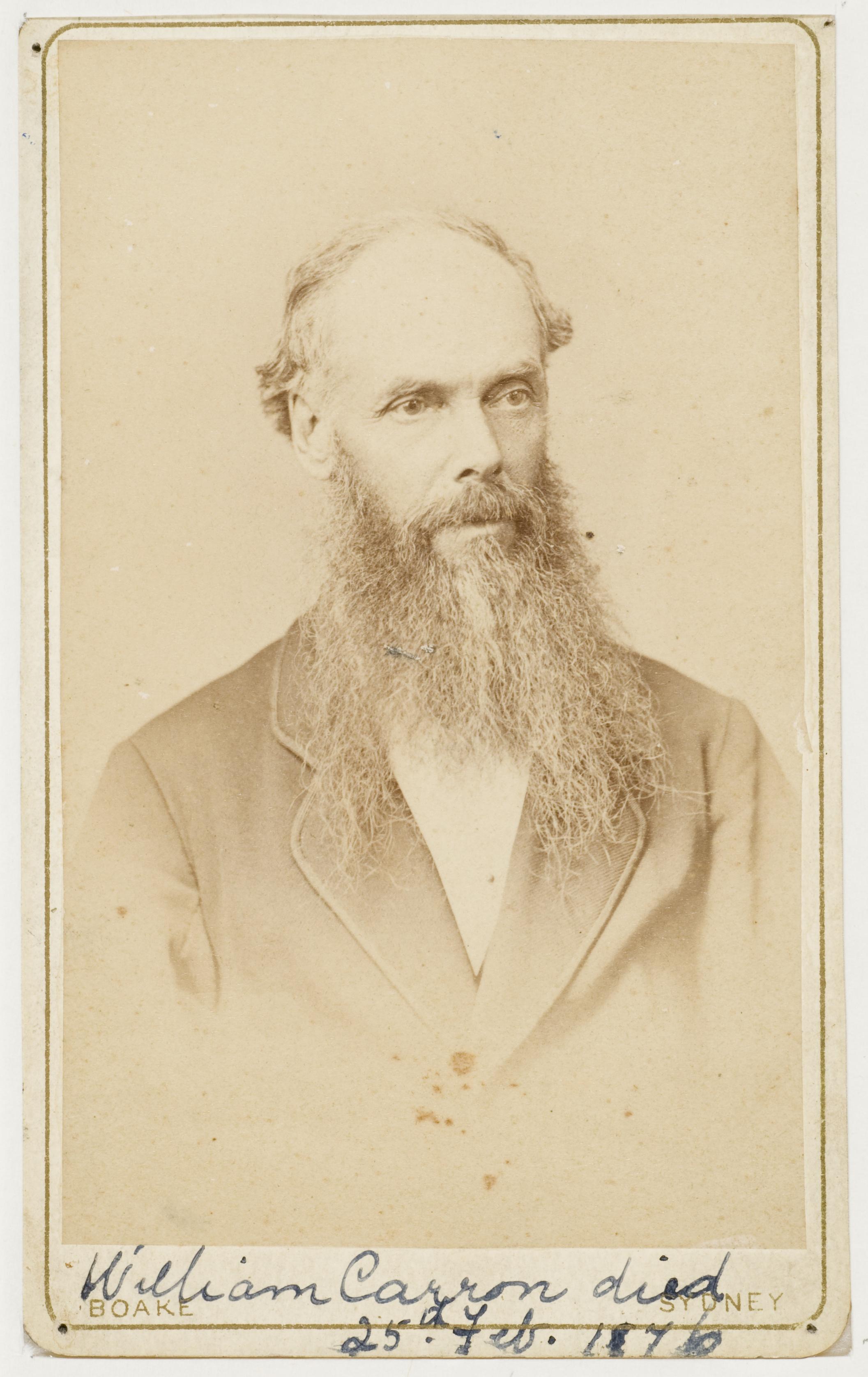

William Carron emigrated to New South Wales with his wife in 1844.

He had worked in the botanic gardens at Cambridge University and on his arrival in Sydney assumed responsibility of Alexander Macleay’s fine collection of plants at his home in Elizabeth Bay. In 1848, while managing Shepherd’s Darling Nursery in Glebe, he was recommended by Botanic Gardens Director Charles Moore to accompany Assistant-Surveyor Edmund Kennedy on his next expedition.

In April 1848 they set off north in the ship Tam O’Shanter from Sydney to traverse the Cape York Peninsula, unaware that fellow explorer Ludwig Leichhardt had been sighted for the last time setting off from a station on the Darling Downs on 3 April. It is believed Leichhardt died somewhere in the Great Sandy Desert.

Kennedy and his party of 13 were delivered to Rockingham Bay in May 1848, landing in thick scrub and swampland. The harsh terrain of the peninsula proved incredibly challenging, and the party spent whole days cutting through dense scrub. Despite the extreme conditions Carron managed to identify and document the plants he saw.

Over six months, the party slowly succumbed to sickness and fatigue, eight men died of suspected starvation, another from accidental gunshot, and Kennedy was speared to death in a conflict with local Aboriginal people.

Kennedy’s papers were buried by Aboriginal tracker Jacky Jacky for safekeeping, 32 km from the tip of Cape York. They were later retrieved by Thomas Beckford Simpson, Captain of the Freak, who was commissioned to search for traces of Kennedy’s expedition. These papers are in the State Library’s collection.

Picked up at Port Albany, Jacky Jacky was able to lead the ship Arial back to Weymouth Bay where they found Carron and convict William Goddard barely alive. Carron was in a skeletal state with his elbow and hip bones showing through his skin. An abstract of Carron’s journal and a portion from 13 November to 30 December were salvaged. His original journal and all his plant specimens had to be left behind when he was rescued.

While the long-term effect of this horrific experience on Carron’s physical and mental health can only be imagined, he lamented the loss of his specimens. ‘All my specimens were left behind which I regretted very much,’ he wrote in his journal, ‘for, though much injured, the collection contained specimens of very beautiful trees, shrubs and orchideae.’

Using descriptions from Carron’s published account, Hauser was able to identify the same plants. She took photographs and collected plant specimens, which she carefully stored in a handmade press. Then each evening she sat in the camp and made detailed pencil sketches in preparation for the final botanical artworks that would take more than two years to complete.

By the side of a small stream running through the flat ground, I saw a curious herbaceous plant, with large pitchers at the end of the leaves. It was too late in the season to find flowers, but the flower stems were about eighteen inches high, and the pitchers would hold about a wine- glass full of water. This interesting and singular plant very much attracted the attention of all our party.

— W Carron, 13 & 14 September 1848, from Carron’s narrative for accompanying illustrations by Janet Hauser. Pitcher Plant.

The trip was a moving experience for Hauser. ‘There were a couple of occasions when I felt Carron’s presence guiding us,’ she says. ‘Driving up to the top of Tully Gorge one day took us an hour but took the party many weeks. One day we stopped spontaneously at a spot along the route to look at a tree and there right below us was one of the geological formations described by Carron in his narrative, black basalt columns rising from the creek bed along the Gorge wall. It felt as if he had willed us stop to see them too.’

Having worked in the field of botany, Hauser had experienced the thrill of botanical discoveries herself. During her expedition she often found herself thinking from Carron’s perspective: ‘I could well imagine his wondrous excitement as a botanist and most certainly his bewilderment at being confronted with the great array of unknown native plants of northern Australia.’

As well as being the only complete first-hand account of the disastrous Kennedy expedition, Carron’s narrative made it possible for Hauser to finish her project and give the dedicated botanist the recognition he deserved.

She produced 37 artworks in total, most of which featured in her 2017 exhibition A Tribute to William Carron at Yamba Museum on the New South Wales north coast, where they were displayed with Carron’s corresponding descriptions. Several of the drawings were sold during the exhibition and the remaining 21 are now held by the Library.

Read Narrative of an expedition online. This item has been transcribed.

In reconstructing the botanical illustrations of the specimens collected by Carron, Hauser’s drawings serve as a contemporary visual reference to the historical written record of the expedition. If Carron’s specimens from the expedition had not been lost, he would have undoubtedly gained greater recognition for his significant scientific contributions to the knowledge of Australian indigenous plants. It is likely that his specimen collection from the Cape York Peninsula would already have been recorded for future reference in the form of botanical drawings. But using historical records, Hauser has gone some way towards correcting this omission, bringing to life the work of a man who dedicated his life to botany. Her delicate drawings bring a bittersweet sense of closure to a project that began over 170 years ago.

Sarah Morley, curator

This story appears in Openbook Summer 2020.

The Library holds correspondence related to the Kennedy expedition, several of William Carron’s field books from later in his career and his scrapbook of pressed ferns. His brass microscope is on permanent display in the Library’s Collectors’ Gallery.