When Winston Churchill came to power in Britain in May 1940, one of the first decisions of his government was to arrest, intern and ultimately deport thousands of ‘enemy aliens’ to Canada and Australia for fear that they might secretly help to orchestrate an invasion of Britain. On 10 July 1940, the British troop ship HMT Dunera departed Liverpool, Britain, with about 2120 male ‘enemy aliens’ on board. Many of the internees were Jewish and had fled to Britain as refugees from Hitler’s regime. Others had been there for years and had made their lives there. Though the Dunera internees did not know it when they left England, theywere destined for Australia. This group of men, aged from 16 to 66, would later become known as the ‘Dunera boys’.

Conditions on the Dunera were dire. The ship was grossly overcrowded, with men crammed into appalling living quarters below deck. A few internees found hammocks, but most were forced to sleep wherever they could find space, including on tables and the ship’s floor. Toilets overflowed, further poisoning the stale air. British soldiers assigned to guard the Dunera internees treated their charges with brutality, abusing them and stealing their possessions. Several internees aboard the Dunera were stabbed by British bayonets. The artist–designer Georg Teltscher reported having a panic attack in the stifling conditions; when he raced up to the deck for fresh air, he was severely beaten.

Somehow, the artists on board found time and space to depict their surroundings, though their materials were rudimentary. With paper in short supply, many artists were forced to draw on toilet paper. One internee, Robert Hofmann, was a renowned portrait artist from Vienna. His keen eye for faces shows in a rare and sympathetic picture of a Dunera crew member, a lascar. Lascars were sailors from India and South-East Asia employed as crew on British merchant ships. Lieutenant Colonel William Scott, the officer in charge of the British guards aboard the Dunera, blamed the lascars for the looting that occurred on the ship, though he knew well that it was his soldiers who were responsible.

The Dunera docked in Sydney on 6 September 1940. By next morning, the majority of the internees had been transferred to the remote, rural town of Hay in the Riverina region of New South Wales. The harsh climate, and their surroundings, shocked many of them. Hay was in drought and everywhere there was dust. Dry, relentless heat and swarms of flies added to the internees’ sense of dislocation. So unfamiliar was the landscape to European eyes that many labelled the Hay plains a ‘desert’. Not even the presence of the Murrumbidgee River, which meanders past Hay, tempered the idea that the Jews had, once again, been led into the desert.

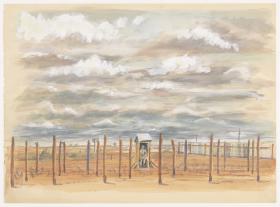

Many artists wasted no time in trying to capture this new and alien world. Wide skies and the flatness of the landscape, studded with seas of fence posts, are common themes in artworks done in Hay, such as in a landscape painting by Georg Teltscher (below). Teltscher was fond of disguising words and messages in his work: the weeds caught in the wire at the left of the picture appear to spell out ‘G’day’.

In 1941, Australian authorities decided to move the Dunera internees from Hay to Tatura, in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley. In May of that year around 400 men were taken first to Orange, because the Tatura camps were not ready to accommodate all the internees. Some of the 400 were chosen for Orange so that they might recover from sickness and general ill health; older men especially were pleased to have the chance to spend time in a ‘European-like’ climate. Artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack wrote to his daughter after arriving in Orange: ‘It is a great relief for all of us to see green grass again after having lived such a long time in desert-like country.’

Many of the most accomplished Dunera artists were among those interned for around six weeks at Orange. While this was a coincidence, the effect was profound. They produced a remarkable visual record of their time at Orange. Indeed, their artworks have revealed more than the documentary record about internment at Orange. Probably some artists were inspired by the landscape, more familiar to the European eye than that around Hay. Where flatness was a characteristic feature of works done at Hay, the opposite is true of Orange. The peaks of the hills and the grandstand at the Orange Showground — a popular motif — gave artists a new frame for their surroundings. Others may have been stimulated by the measures of freedom allowed at Orange. Numerous artworks reflect vantage points beyond and above the camp. At Hay, the internee artist invariably looked out through barbed wire. In Orange, we see more varied perspectives.

Many artists in internment depicted scenes of everyday camp life. In the absence of cameras, the hundreds of sketches and paintings that Robert Hofmann created of his fellow internees function as our best pictorial record. Many of these portraits are dated and labelled, Hofmann’s meticulousness a boon forhistorians seeking new knowledge of camp life. Elsewhere, internee artists depicted everyday activities, such as in Erwin Fabian’s watercolour where men peel potatoes. Fabian was adept at capturing the monotony of internment, a skill that won praise from a fellow internee: ‘in a few battered tins, logs of wood, ash, and rubbish, he gives the whole atmosphere of our dismal surroundings’. For Fabian, depicting the internee experience meant capturing not only the drabness, but also precious moments of relief, humour and beauty.

Camp education scenes were another part of the artist’s everyday work. Many Second World War internees turned to education to sustain their lives behind barbed wire, and the Dunera boys were no different. As soon as the Dunera left Liverpool, internees began to offer lectures and classes in their fields of expertise. Their educational enterprises continued in Australia, where informal camp universities were established. Courses were taught on languages, philosophy and art history, among many other subjects. Georg Teltscher was one of the teachers at Hay. The young artist Klaus Friedeberger recalled attending his classes on modernism and the Bauhaus. Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack offered classes in printmaking and colour theory at both Hay and Orange. For Hirschfeld-Mack, the lectures, alongside activities such as ‘camp-fires, cabarets, choirs, concerts’, provided diversions and entertainments ‘to keep up morale’.

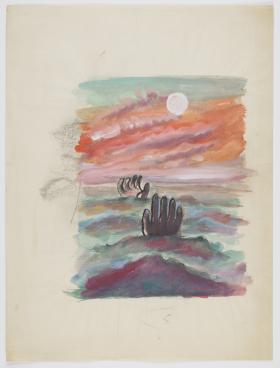

An intriguing feature of the artworks produced in internment is the many images of the camps after dark. Daytime works record everyday life and the mundane realities of internment, while the night-time images are often more confronting in their explorations of internees’ psychological moods. These images began early in the Dunera boys’ experiences of Australian internment. When the internees arrived in Hay on 7 September 1940, they were greeted by a massive dust storm that rolled across the flat like a tsunami, swallowing people and landscape in its path. Hirschfeld-Mack created two frightening depictions of this dust storm, which he portrayed as a demonic figure. Fabian was another artist whose works differ from day to night. Though a young and relatively inexperienced artist, his skill was such that he was able to create a new, specific genre: nightmare images of camp life. These works convey the sense of dislocation and loss that afflicted many internees. At night, surreal and frightening landscapes are populated by demonic, beast-like figures that roam freely around the camp. By combining expressionism and surrealism, Fabian was able to capture a psychological reality that was not necessarily surreal. Refugees and internees did not need horror or ghost stories to ignite their imaginations. As Hannah Arendt later noted, their minds were flooded with the distress of their everyday reality.

The most famous image of internment in Australia was created by Hirschfeld-Mack. His woodcut print, originally untitled but subsequently known as Desolation, depicts a solitary figure in a long coat silhouetted against a barbed-wire fence. This lone figure peers into the void, perhaps reflecting on the vast distance between him and the world he once knew — a world thrown into turmoil. An inverted Southern Cross constellation hangs in the night sky beyond. In a simple, direct style, the work concentrates the psychological impact of being bundled across the world with no prospects and few liberties.

In contrast to Hay and Tatura, internment life at Orange is not extensively detailed in archival records and personal histories. Information about living arrangements, for instance, is relatively scant. There were two compounds at Orange, with twelve huts in one and eight in the other, and a common kitchen shared between every four huts. The huts were made of corrugated iron and accommodated 25 men, who slept on bed boards and straw mattresses on the floor, a less comfortable arrangement than the bunks they had at Hay. The Orange camp was less spacious than Hay, which disappointed some internees, though most warmed to the town itself. ‘A marvellous place’, one internee observed of Orange in his diary.

In July 1941, the 400 or so Dunera internees who had been sent to Orange joined the remainder of their cohort in Tatura. Most were at Tatura for relatively short periods. Some were released for civil work in Australia; others returned to Britain, or took other paths to freedom. From early 1942, internees could win their freedom by enlisting in the 8th Employment Company, a labour unit in the Australian Army. Hundreds enlisted, determined to contribute in some way to the war effort and to the anti-fascist cause.

After the war ended, less than half of the approximately 2100 Dunera men remained in Australia. In the years that followed even more departed the country; only about 700 remained in Australia long-term. Of those who stayed, a relatively small number, perhaps 50 or so, won fame and success, and their stories have had a disproportionate effect on Dunera memory. In modern Australia, the Dunera story tends to be rendered as a triumph. This narrative ignores the stories of the vast majority of Dunera internees, which remain all but unknown. Some men were broken by their Dunera experience, while others melted into Australian post-war life, content to leave their devastation and discomfort in the past.

The recent Dunera acquisitions made by the State Library of NSW, mainly from the private collections of friends and family, will help to produce a fuller, more complete picture of the Dunera internees. These artworks give us glimpses of their triumphs, to be sure, but more importantly they tell also of the tragic and the mundane aspects of their story. Eight decades on, this art is returning to the place it was created.

Enemy Aliens: The Dunera boys in Orange, 1941 is on show at the Orange Regional Museum from 19 November 2022 – 23 April 2023.

Kate Garrett is a German translator with a particular interest in the translation of Second World War documents and correspondence. Her poetry translations appeared in Dunera Lives: A visual history and she provided the translations for Shadowline: The Dunera diaries of Uwe Radok (both Monash University Publishing).

Andrew McNamara is an art historian who has worked on the internment experience of former Bauhäusler Hirschfeld-Mack and Teltscher for Bauhaus Diaspora and Beyond (Melbourne University Publishing). His essay on night-time internment imagery, ‘When the reality is Unreal: Camps, Towers and Internment’, was published in Realisms of the Avant-Garde (De Gruyter).

Seumas Spark is an historian with a particular interest in the Dunera internees. He is co-author of the two-volume history Dunera Lives (Monash University Publishing, 2018 and 2020), and co-editor (with Jacquie Houlden) of Shadowline: The Dunera Diaries of Uwe Radok (2022).

This story appears in Openbook summer 2022.