People often ask why writing is so important to me. But like anything to do with human desire, it’s hard to explain in a soundbite. Writing makes me happy. Writing helps me think, understand and express myself. Writing is almost as natural and necessary to me as breathing.

And writing is in my blood. I come from a long line of writers, stretching back hundreds of years. And that family history sparked one of the most joyous yet challenging books I have ever written.

When I was a child, my brother, sister and I were told stories full of romance, drama and tragedy about our great-great-great-great-grandmother Charlotte Waring Atkinson, who wrote the first children’s book published in Australia.

Charlotte was born in London in 1796 to a wealthy family that traced its lineage back to William de Warenne, a Norman knight who fought at the side of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. According to family myth, he was rewarded with a title, vast swathes of English land, and the hand of the king’s daughter in marriage.

Charlotte’s father lost his wealth when she was still a girl, and she had to go out to work as a governess at the age of 15. When I came across a published letter by Charlotte Brontë in which she describes the governess’s life of ‘inexpressible misery’, I felt so sorry for my ancestor may have suffered the same loneliness, humiliation and unkindness.

When she was 30, Charlotte applied for a job in far-off Sydney to teach the children of pastoralist and politician Hannibal Macarthur. Twenty-four other governesses applied — I imagine them sitting in a row, with their high-necked blouses, long skirts and neat button-up boots, hands folded primly in their laps — but only Charlotte was willing to risk the danger of a long voyage to that mysterious land ‘down under’. ‘Though I must travel first-class,’ she told them.

When Charlotte was on board The Cumberland, ready to set sail from London, a handsome young gentleman came aboard and tipped his hat to her. His name was James Atkinson, and it was love at first sight. Within three weeks, they were engaged to be married.

According to family lore, James proposed to her after a great storm at sea. Charlotte was almost washed overboard, and her fiancé saved her then wrapped her in his plaid cloak to keep her warm. So romantic! we used to sigh as children.

After Charlotte and James were married, he built her a beautiful sandstone house named Oldbury, near Sutton Forest in the Southern Highlands. They were very happy, and had four children in quick succession: Charlotte Elizabeth, Jane Emily, James John and Caroline Louisa, who was called by her second name. When Louisa was still only a newborn, her father James died suddenly from typhoid, and Charlotte was left a young widow, struggling to run a vast property worked mostly by convicts.

In January 1836 Charlotte rode out with her overseer George Barton to check on her flocks near the forest of Belanglo. They were attacked by bushrangers, and Barton was viciously flogged. We do not know what the bushrangers did to Charlotte. But considering one of them was John Lynch, known as the Berrima Axe Murderer, we fear the worst.

Three weeks after the attack was reported in the Sydney Herald, Charlotte made what turned out to be the worst mistake of her life. She married Barton.

He proved to be a violent drunkard, and three-and-a-half years later Charlotte fled Oldbury with her four children. They took only what could be carried by a few bullocks and rode on horseback through the almost impenetrable gorges of the Shoalhaven River and — eventually — to safety in Sydney.

One of the first things Charlotte did was apply to the police for protection against George Barton, chilling proof that he had been physically violent during their marriage. With no income at all, she applied to the courts for the proceeds from Oldbury, as laid out in James Atkinson’s will. ‘Her situation is extremely distressing,’ her solicitor wrote. ‘She assures me she and the Children are literally starving.’

In retaliation for her ‘imprudent’ marriage to Barton, the trustees of the will declared she was not a ‘fit and proper person to be the Guardian of the Infants’. They applied to the courts to have the children given into the guardianship of a stranger. It didn’t matter who, as long as it was a man.

At enormous emotional and financial cost, Charlotte fought the case all the way to the NSW Supreme Court. At one point, she was charged with contempt of court for her impertinence. Finally, on 9 July 1841, Chief Justice Sir James Dowling found emphatically in her favour. He ruled that ‘it would require a state of urgent circumstances to induce the Court to deprive [the children] of that maternal care and tenderness, which none but a mother can bestow’.

It was a resounding victory, both for Charlotte and for the rights of Australian women.

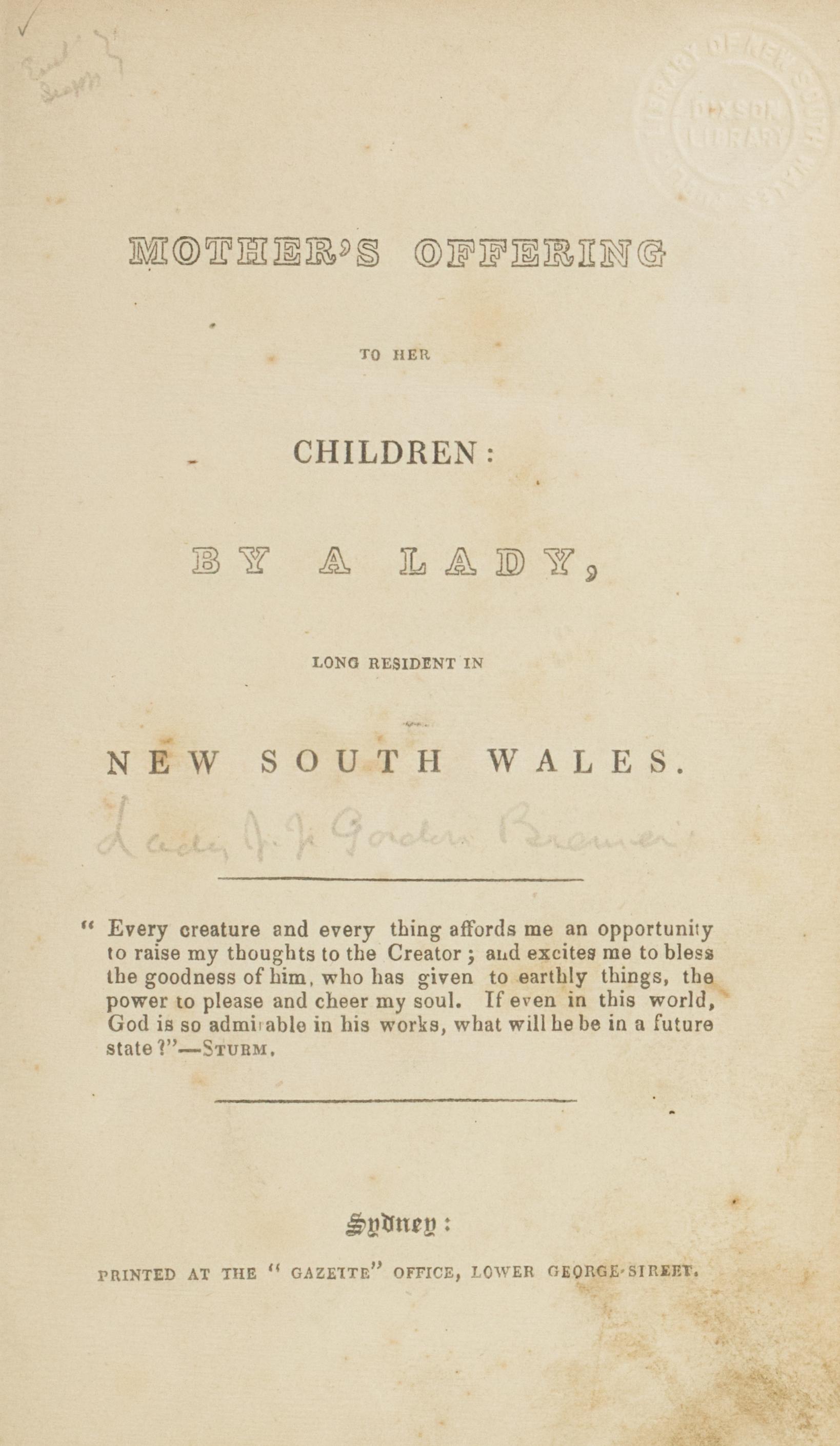

Five months later, just a week before Christmas, A Mother’s Offering to Her Children by a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales was published. Charlotte had struggled through almost impossible obstacles to become Australia’s first children’s author.

When my sister Belinda Murrell and I grew up to become writers, people would say, ‘You should write a book about Charlotte!’ And as the 180th anniversary of the publication of A Mother’s Offering drew closer, we signed a contract for an intimate biography/memoir.

We began our research at the State Library of NSW, where the Mitchell Library collection holds one of the best archives of Atkinson-related material in the world. Among its treasures is a memoir by Charlotte’s youngest daughter Louisa Atkinson, the first Australian-born female novelist, journalist and botanist. It confirmed several family stories, including the account of our French noble blood, which made us laugh because we’d believed the story had been glamorised!

It was moving to read our great-great-great-great-aunt’s handwritten life story, written for her newborn daughter. Sadly, her reminiscences finish halfway through a sentence. Two weeks after her daughter’s birth, Louisa looked out the window and saw her husband’s riderless horse gallop into the yard. Imagining the worst, she had a heart attack and dropped dead. When her husband limped home later, he found her lifeless body beside the baby’s cradle.

In the archive we also found the tiny Bible given to Charlotte’s son James John at his christening, along with old photographs of Oldbury and family portraits by the young Atkinsons.

An album of watercolour drawings from around 1848 is attributed to Charlotte’s daughter Jane Emily Atkinson, with a comment in the catalogue that it was unclear whether Jane was ‘the artist of these drawings or merely the owner of the album’.

The album’s donor had written that the sketchbook was a ‘a gift to Emily / not her work / certain ... by her brother’.

We knew that Charlotte’s son James John was only 16 at that time and were not expecting anything very special when we ordered up the drawings. But what we discovered was the greatest treasure of all. The handwritten annotation by Charlotte’s great-granddaughter Janet Cosh had been misread, and actually said, ‘a gift to Emily /not her work / certainly by her mother’.

The age-spotted pages were filled with exquisite family portraits by Charlotte Waring Atkinson, including a self-portrait of the artist wrapped in a plaid cloak just like the one she wore in the romantic story of her courtship with James.

Belinda and I had been intrigued by contemporary references to Charlotte having published ‘several useful works for children’, and her biographer Marcie Muir had left a note in the National Library of Australia mentioning a ‘very entertaining & instructive little work for children entitled P.P.’s Tales’. We came across an illustrated chapbook published in London in 1832 titled Amusing and Instructive Stories by Peter Prattle, which is set in Australia and was reprinted with additional stories in 1842.

When I looked at both editions in the Mitchell Library Reading Room, I soon realised it was highly likely that they were by Charlotte. As well as many parallels in style, theme and language, one story features two girls keen on botany named Caroline and Louisa, the given names of Charlotte’s daughter who became a noted botanist. If Charlotte wrote under the pseudonym ‘Peter Prattle’, then she is the author and illustrator of some of the first children’s stories set in Australia, as well as the author of Australia’s first children’s book.

The search for Charlotte had many heart-wrenching, perplexing and thrilling moments. It was wonderful to finally bring our ancestor out of the realm of family stories and share her extraordinary life.

Novelist Kate Forsyth was the Library’s 2019 Nancy Keesing Fellow, and is the co-author with Belinda Murrell of Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author (NLA Publishing, 2020).

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2021.