Truth and photography

Truth and photography

Within weeks of being at the front, Hurley clashed with the Official AIF historian, Captain Charles Bean, about truth and photography. Both men were officially appointed to the Australian War Records Section of the AIF to document the war – Hurley through photographs and Bean through writing. Hurley argued that as war was conducted on a vast scale, it was impossible to capture the essence of it in a single negative. He wrote in The Australasian Photo-Review in 1919:

None but those who have endeavoured can realise the insurmountable difficulties of portraying a modern battle by the camera. To include the event on a single negative, I have tried and tried, but the results are hopeless. [. . .] Now, if negatives are taken of all the separate incidents in the action and combined, some idea may then be gained of what a modern battle looks like.[5]

Hurley referred to these combination prints as ‘Photographic Impression Pictures’ – 'pictures made to produce a realistic impression of certain events by the combined use of a number of negatives.' It was a technique he had employed to great effect for his work in Antarctica. Bean referred to them as ‘fakes’. He vowed: 'we will not have it at any price'.[6]

Hurley stood his ground. He would not compromise his art-form, or what he saw as his duty to portray the true horrors of war. He planned to resign his official commission.

By chance, he met Sir William Birdwood, General Officer Commanding of the AIF. Birdwood was dismayed to hear that Hurley was planning to resign and brokered a compromise: Hurley would be allowed to print six composite photographs if he would continue as an AIF Official Photographer. Hurley agreed. Bean felt the composites were compromising the truth.

Some scholars [7] have argued that by creating composite images, Hurley was simply following a practice in photography which dates back to American Civil War photographer George Barnard. Certainly the Canadian photographers at the western front had few qualms about the practice. While controversial, it is important to remember that the composite photographs accounted for only a fraction of Hurley’s World War One work.

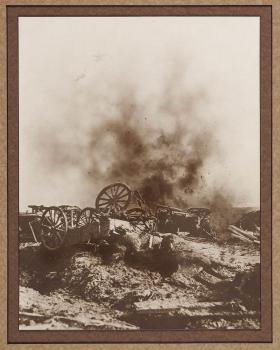

Hurley originally titled this photograph 'Battle scarred sentinels' – a reference to the burnt out tree trunks that line the road. The smoke from an explosion was added in the dark room by superimposing two negatives. In the catalogue for the exhibition that was shown in Sydney in 1921, the caption for this photo was 'Death’s Highway. An exposed roadway on the battlefield'.

The smoke adds an element of fear and gives the impression that the soldier is taking cover behind a tree stump. Without the smoke, it is possible to think of the soldier as clambering through the slippery mud.

Hurley has added smoke from an explosion to this photograph which he titled 'Hellfire Corner'. He wanted to show the difficulty of transporting men and ammunition in the thick, sucking mud. The explosive smoke gives the impression that the carts have been overturned by the shell, when it could have been due to the attempts to push and pull them through the mud.