When it comes to the natural world, we take far more than we give back. Far from our humble beginnings living in harmony with the land and the ocean, the human collective has harnessed our power and we have organised ourselves into magnificent cities and cultures. While our ancestors were striking flint to start a fire, now we can create nuclear fusion, the very process that powers our sun and the stars. By many measures, we have performed unimaginably well. But we have forgotten that nature is not a part of our world — we are a part of nature.

Our temporary lease here on Earth is just that, ephemeral. Modern civilisation, steeped in culture, technology and belief in progress, represents a mere 0.00002 per cent of Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history. Given our fleeting existence, we should revere the processes our planet has been undergoing for billions of years, processes that will continue long after we are gone. Instead, we are in competition with natural systems and outcompeting them.

Luckily for us, there’s a natural kingdom with a billion years of experience waiting to share its wisdom. The kingdom of fungi offers us a chance to redefine our relationship with the natural world and provides glimmers of hope amid the accelerating rate of climate change.

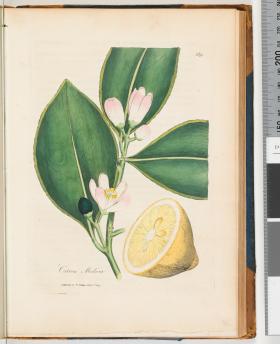

Fungi shape and transform environments. They underpin the wellbeing of nearly all terrestrial ecosystems. Despite spending most of their lives hidden underground, or inside plants and animals, fungi are responsible for critical ecological processes. Some fungi weave through the earth, decomposing matter and recycling nutrients to build healthy soils where plants and animals can flourish. They are the interface between death and life — without them, the world would be buried under fallen trees, the remains of animals and infertile soil.

Various fungi form intimate and intelligent partnerships with all forms of life, supporting the health of most — if not all — organisms. The production of beer, wine, chocolate, bread, penicillin and detergent depends on fungi. A potent group, known as psychedelics, contains psychoactive compounds that can initiate transformative experiences of love, creativity and connection. We both grew up in ethnic Chinese families where traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practices are woven into the way we eat and live. Revered in TCM, fungi such as reishi, enoki, wood ear are often treated as both food and medicine. We were also fortunate enough to have had transformational psychedelic experiences, which have shaped the trajectory of our lives.

It is safe to say that without fungi, the world as we know it would not exist. Fungi are nature’s alchemists and may hold untold answers for our future on Earth.

The kingdom of fungi offers us a chance to redefine our relationship with the natural world ...

Neither plant nor animal, fungi represent a distinct third kingdom, overlooked for much of scientific history. Unlike plants that photosynthesise, and animals that ingest and digest food, fungi secrete enzymes into the environment to break down food externally, before absorbing it into their mycelium, a root-like network that grows through the soil. These enzymes are similar to those in our mouths — leave a piece of bread on your tongue and within seconds, digestive acids in your saliva will turn the bread into wet mush. But fungi have a remarkably wide taste palette compared to humans, consuming everything from stale bread to plastics and even nuclear waste. This method of feeding means fungi can penetrate the toughest of substances to extract nutrients, before transferring them into their cells.

Fungi have evolved to feed on almost any organic and non-organic matter. Parasitic fungi infect and feed off living hosts. Saprophytic fungi decompose dead or dying matter for energy. Some fungi form mutually beneficial relationships with plants or animals for food. The largest groups of these ‘mutualists’ include mycorrhizal fungi, which are networks of underground mycelium that interact with the root systems of plants. Fungi share nutrients and water with plants in exchange for sugars. Mycelium is only one cell wall thick, so can easily extract nutrients from a range of complex materials, breaking them into elementary substances such as water, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, phosphorus and calcium — superfoods that allow plants to flourish.

Mycorrhizal relationships are far more complex than a single partnership between a fungus and a plant. Hundreds of mycelia can be attached to one plant and, conversely, a mycelium can be attached to hundreds of plants. Mycelium is so fine that a teaspoon of soil can hold hundreds of kilometres of it. Over an area as large as a forest, that is a long information highway for fungi and plants to relay resources and chemical signals. And they do, constantly. Forests, grasslands and woodlands are not landscapes of individual trees competing with one another for survival. These ecosystems have been formed over millions of years, and their participants have the ability to negotiate, cooperate, trade, steal and compromise — all in the absence of a brain. Fungi connect them all, underground mycelia weaving the forest into a dynamic network of incredible scale.

Dr Suzanne Simard, an ecologist at the University of British Columbia, made a striking discovery, published in Nature in 1997: that carbon produced from one tree can be shared with its mycorrhizal partners and with other trees. She called this the ‘wood wide web’. Today, the phrase ‘wood wide web’ is used to describe the mycelial highways that function like a forest’s organic internet. Plants within the network can transfer sugars, hormones, stress signals and carbon. Simard mapped the mycorrhizal networks in numerous forests and found that they were structured similarly to neural networks in the brain, or like nodal links within the internet. The oldest and largest trees had the most mycorrhizal connections, trees that Simard called ‘mother trees’. These social ‘creatures’ supported the rest of the network by feeding seedlings, injured or shaded trees, warned others of attacks, and transferred their own nutrients to neighbouring plants before they died.

Yet not all scientists agree that fungi and trees behave altruistically. Dr Toby Kiers, professor of evolutionary biology at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, for example, believes that ‘both parties may benefit, but they also constantly struggle to maximise their individual pay-off’. Using market economics as a metaphor, Kiers’s team published studies showing that plants and fungi trade under free market principles. In some experiments, fungi hoarded nutrients in their mycelium to decrease the supply. With increased demand from plants, fungi inflated the price for the same nutrients. In Kiers’s work, capitalist fungi and plants display similarities to humans in their ability to manipulate the supply and demand of the forest market.

Fungi are sentient without thought, sophisticated without cognition. It’s a fungal world, we are just living in it.

It’s a fungal world, we are just living in it.

Fungi as a water filter

Mycelium is known for its insatiable hunger for organic matter. The common oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), for example, is able to process and neutralise bacteria such as E. coli, working with its mycelial membrane to filter out microbial pathogens from contaminated water. A ‘mycofilter’ can be created with a hessian sack filled with wet straw and woodchips and inoculated with myceli. Inexpensive and simple to set up, the small size of the mycofilter means that it can be installed around farms, urban areas, roads and factories. A roadside mycofiltration system can help decontaminate wastewater before it makes its way back into our waterways.

Tradd Cotter, an American mycologist and owner of the company Mushroom Mountain, runs workshops on setting up mycofiltration systems. ‘We’re using a cage that looks like a crab pot, that can be refilled with wood chips. It’ll last for a year or two. And if the cage stays put, it can be emptied out and refilled with new wood chips.’ Mycofiltration is in its infancy, but many people are experimenting with this fungal capability.

Fungi as a forest and soil builder

‘Mycoforestry’ refers to the use of fungi as a forest and soil builder. Wood debris in forests from logging can be chipped into smaller pieces, then inoculated with native saprophytic fungi species to accelerate decomposition of organic matter. This redirects vital elements and nutrients back into the soil for use by the rest of the forest. Fungi also produce glomalin, a sticky substance that binds soil particles and builds soil architecture, and which fungi use to store carbon. Trees connected to a mycelial network absorb carbon from the atmosphere and transfer it into the mycelium for storage. Fungi can play a critical role in regulating the global climate.

Fungi as a farmer’s friend

Bill Mollison, co-founder of permaculture, spent a decade in the Tweed Valley in northern NSW designing principles for farming inspired by nature. Permaculture creates self-sufficiency, regeneration and interconnectedness that can be applied to all aspects of life. Think of rain barrels, solar panels, composting bins, worm trays, chicken coops, home mushroom farms or experiments with fermentation. In fact, the prevalence and centrality of fungi in permaculture systems has spawned the term ‘mycopermaculture’.

Imagine a mycopermaculture system in your garden, which recycles garden waste into nutritious food for fungi. As the mycelium consumes your garden waste, it creates a launchpad for the fungi sporing bodies to develop, creating an abundance of potential edible and medicinal mushrooms and fodder for animals roaming your garden (animals love mushrooms). The by-products can be put into your garden’s soil to enhance its nutrients and microflora. Small and slow systems are easier to maintain than big ones. With patience, commitment and the right resources, even city-living, first-time gardeners can make a big difference.

Fungi provide us with the hope that we can not only survive, but thrive, despite the challenges that we face on our planet. Fungi may be one more step towards healing our planet.

Michael Lim was born in Sydney. When aged 21, he co-founded an online brand that is now one of Australia’s largest eyewear chains. Early transformational experiences with psychedelics inspired his fascination with the fungi kingdom and prompted a career change. He now dedicates his time to researching fungi, psychedelics, ecology and anthropology.

Yun Shu was born in Shanghai. After a successful career in the banking sector in Sydney and London, she took a more spiritual path and is now dedicated to the study of consciousness, using language and culture as tools for connection and healing.

Michael Lim and Yun Shu are co-authors of The Future is Fungi, published by Thames & Hudson in 2022.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2022.