When we imagine the liberation of Nazi concentration camps 75 years ago our minds tend to fix on the moment when the gates were opened and Allied forces moved in to behold the immense human tragedy.

Auschwitz was liberated by the Soviets in January 1945. Buchenwald and Dachau were reached by the Americans, and Ravensbrück by the Soviets, in April. In May, Mauthausen was liberated by the Americans and Theresienstadt by the Soviets. Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, near the German city of Hanover, was liberated by British forces on 15 April 1945.

Australian nurse Muriel Knox Doherty arrived at Bergen-Belsen three months later, on 11 July, and took up the position of Chief Nurse and Principal Matron. A clinical nurse, nurse teacher and administrator, Doherty had begun her long and influential nursing career a world away at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1921.

During the Second World War, she had served with distinction in the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service. In 1945, when ‘the plight of the millions of displaced persons in the former occupied territories became increasingly compelling’ to her, she applied for a position with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and was assigned to Bergen-Belsen.

By 1945 thousands of people — including Jews, Roma or Gypsies, political prisoners, prisoners of war, homosexuals and other groups considered to be undesirable — had been transported to BergenBelsen, which had been established two years earlier as a transit camp for prisoners of the Nazi regime. Held in appalling conditions, many thousands died of starvation and disease. It was at Bergen-Belsen that Anne Frank and her sister Margot died of typhus in March 1945, only weeks before liberation.

When the British arrived at the camp they were unprepared for the scale of misery, cruelty and utter desolation. They found more than 40,000 desperately ill and starving prisoners, and the unburied bodies of 10,000 men, women and children. The death toll continued to rise in the weeks following liberation. The true number of deaths may never be known because, despite an agreement with the British, all remaining camp records were destroyed by the SS soon after liberation.

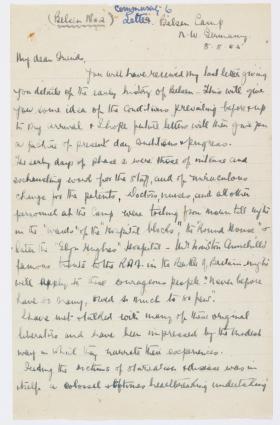

When Doherty took up her position she faced the mammoth task of establishing a hospital and nursing the thousands of survivors. Her nursing staff was drawn from many nations, including Germany. One of the major difficulties was formulating a suitable diet for people who had been almost starved to death.

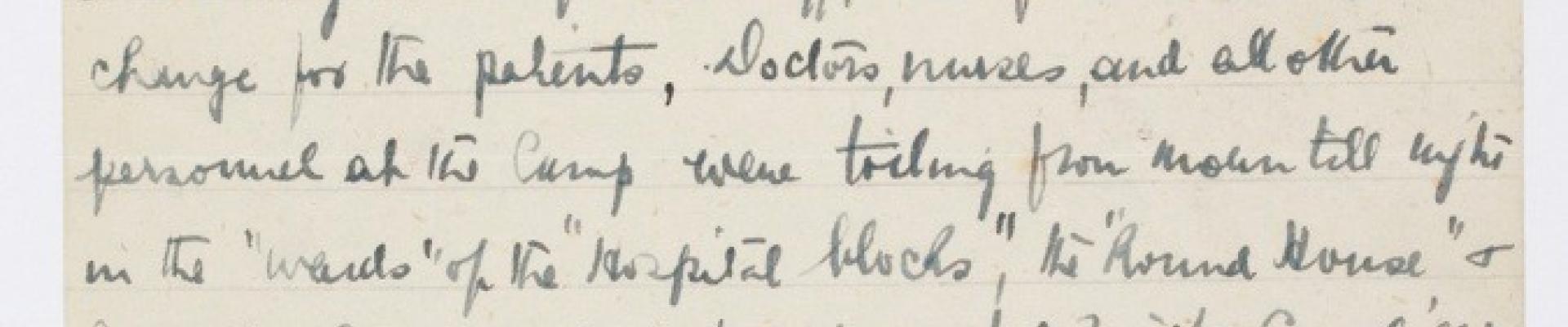

Doherty’s meticulous ‘Community Letters’, written to family and friends in the early morning or late at night, often by candlelight, record her experiences at Bergen-Belsen and her sometimes critical observations of the nursing profession and military establishment.

Addressed to ‘Dear Friends’, her letters describe the horrors of the camp where, she wrote on 27 July 1945, there were ‘some 25,000 living sick who were dying at the rate of 4% (about 1000) per day. In many huts the living were packed on the floors amongst the dead, oftentimes naked. Owing to illness & despair, corpses were often not moved from the bunks which were shared by the living … Faeces were 6” deep on the floor of the huts …’

Surrounded by illness, misery and suffering, Doherty also found moments of joy. Following liberation, Bergen-Belsen became a centre for Jewish and other displaced persons, and on 21 July 1945 Doherty attended a wedding between a young Polish displaced person and a British ambulance driver.

On 1 October she attended the Luneberg Trials of war criminals from Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz. Survivors from Bergen-Belsen gave evidence against the camp commander, Joseph Kramer, who was hanged in December 1945.

Doherty’s letters offer a woman’s perspective on the war and its aftermath and document a rarely discussed facet of Australian wartime involvement. They record the extraordinary suffering of the inmates and the plight of displaced persons tormented by the hopelessness of their situation, many unable or unwilling to return home.

Doherty remained at Bergen-Belsen for seven months and was awarded the Royal Red Cross Medal (1st Class) for her work at the camp. In 1946 she worked in nurse education in Poland before returning to Australia.

Muriel Knox Doherty died in 1988 at the age of 92. In 1960, she had donated copies of her wartime letters and diary to the Mitchell Library with instructions that they not be opened until 2000. These pages capture her insights into what she described as ‘the then unknown, but greatest, yet most tragic experience of my life’.

Louise Anemaat

Executive Director, Library & Information Services and Dixson Librarian

These letters have been digitised and can be read through the Library’s catalogue.