Your thoughts define your reality. You can heal. Choose love. Create success. Magic happens.

Such aphorisms ring through western culture, promising that a positive state of mind will transform a person’s life. These ideas also underpin the self-help and ‘wellness’ industries, with books advising readers on how to live happier, more fulfilling and prosperous lives. And they manifest in the social media profiles of ‘wellness’ influencers who post self-healing slogans alongside pictures of fruit smoothies. The promise is simple: by overcoming internal barriers and adopting a positive mindset, readers and followers can seize transformation, health and success.

One example is ‘Coach Mike’, Mike Bayer, a regular guest on Dr Phil, the American talk show. In his 2020 book Be Your Best Self, he promises, ‘I want to help you discover exactly how you can be you, only better, in order to feel fully equipped for navigating anything and everything.’ A tough talker, Bayer preaches personal responsibility. ‘You can either choose to live in your rut, your anger, or your pain or you can choose to turn your negativity into inspiration.’

Bayer’s ideas are nothing new. Snappy self-help slogans and beliefs owe a sizeable debt to a nineteenth-century movement that claimed that positive and negative emotions determine our material realities.

Known as ‘New Thought’, this philosophy emerged in the United States from the mid-nineteenth century. It came out of the milieu of American Transcendentalism and other religious and scientific investigations into links between mind, body and soul. The mesmeric healer Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866) was its founder.

Psychologist of religion William James, brother of writer Henry James, called this new philosophy a ‘religion of healthy-mindedness’. In his classic 1902 book, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A study in human nature, James outlined how practitioners believed ‘in the all-saving power of healthy-minded attitudes as such, in the conquering efficacy of courage, hope, and trust, and [held] a correlative contempt for doubt, fear, worry, and all nervously precautionary states of mind’.

‘One hears of the “Gospel of Relaxation,” of the “Don’t Worry Movement,” of people who repeat to themselves, “Youth, health, vigor!” when dressing in the morning, as their motto for the day,’ wrote James, nodding to the central role given to positive affirmations.

New Thought flowed across to the Antipodes, as do many American ideas to this day. Australian historians including the late Jill Roe, as well as Frank Bongiorno, have shown that by the late-nineteenth century it infused the worldviews of progressives who turned away from mainline religions to instead seek wisdom and knowledge from within. Often, through healing experiences, they found their way into metaphysical faiths or into sympathetic movements such as Spiritualism, Christian Science and Theosophy.

Snappy self-help slogans and beliefs owe a sizeable debt to a nineteenth-century movement that claimed that positive and negative emotions determine our material realities.

In Sydney in 1898, surveyor-turned-journalist Henry Cardew launched his journal The Metaphysician, which he published for more than a decade under various titles including Progressive Thought, Science of Life and Progressive Thinker. His fixation on progress reflected New Thought beliefs about the continuing improvement of humanity, seen as an inevitable journey towards a new age when peace and love would rule. A higher power or ‘source’ was endlessly accessible, they believed, by turning within. Helpfully, positive thinking could also attract wealth.

Like a proto-Instagram, these magazines — which also explored Christian Science philosophies — included snippets about fasting and bananas, tips for breathwork, advertisements for spiritual healers and herbalists, and muscle-building exercises from the ‘physical culture’ repertoire. Progressive Thought eventually included tear-out calendars with cartoons, aphorisms and a monthly affirmation, for example, ‘I am fearless’ or ‘I will express the divine love in all my thoughts and actions.’

The magazine made explicit a causal link between thinking the wrong thoughts and physical illness. In the very first issue, an article titled ‘Storm Centres’ by EA Pennock drew an analogy between weather patterns, disease and the imperative of cultivating positive over negative emotions.

‘I believe that cancer and ulcer are always expressions of a mental storm centre. An injury may first turn anxious thought to a certain spot, and as it is held there, a centre of impurity and disease is formed, into which all the diseased cells of the body find their way,’ wrote Pennock. He later added that ‘When love rules within and acts upon these cells, and all our energies are used for love’s activities towards humanity, the Divine and heavenly order is being realised’.

From the early- to mid-twentieth century, popular psychology entrepreneurs increasingly repackaged their ideas for people seeking career success. This was a response to both the emergence of the ‘businessman’ as an archetype of modern masculinity and the rise of industrial psychology, an academic area of study that integrated scientific principles of personality and mind into workplace management.

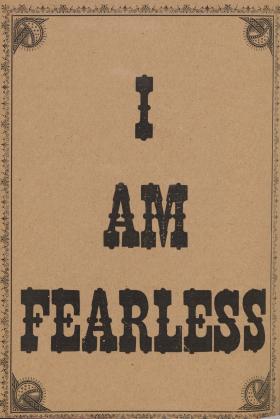

The entrepreneur and vocational adviser Walter S Binks, who was active in Melbourne by the 1920s, sold a gospel of cheer and determination tailored for the workplace. Selling a service in which he claimed to assess someone’s character by reading their head shape and face, Binks remade himself from his earlier calling as a Methodist preacher. Part of this transformation included exchanging his middle name, ‘Samuel’, for the more poetic ‘Shakespeare’, and dubbing his business the ‘Universal Opportunity League’.

A black-and-white photo-portrait of Binks — a man with a severe side-part and a quizzically furrowed brow — graced the early pages of one of his mid-century manuals, The Binks Book: Essays for everyday living. An illustrated book of essays and poems, it emphasised the importance of positive visualisation.

‘Let us start right now to think of the things that we want to happen — and think of nothing else, no unfortunate alternatives, no failures, no disasters. Let us be positive people — the ones who get ambitions realised, by giving the subconscious mind a chance to help them,’ Binks advised.

He outlined instructions for success that would not go astray in many contemporary self-help books: learn more about your mind and aptitude in order to select a suitable career path; set clear, bold goals; ‘be self-assertive’. He reminded readers that ‘You are the person concerned in making a really great success, in every way, of your own life’. And because healthiness stemmed from both mind and body, good diet was essential. ‘Whoever dies a so-called natural death below the age of 120 dies of gastronomic suicide,’ he proposed. ‘You can overcome the disabilities of ill-health, or fear of ill-health. Of course you can.’

These were straightforward rules. But Binks’s oeuvre, which reframed every challenge as a task for positive thinking, revealed the imaginative elasticity required of New Thought’s adherents during times of crisis. Born at the end of the nineteenth century, Binks was a young man when World War I erupted. Facing cataclysm, as with so many of his generation, he reached for the utopian promise of a coming golden age, performing the kind of optimistic squinting that William James considered central to the human condition. As James wrote in The Varieties of Religious Experience, ‘We divert our attention from disease and death as much as we can; and the slaughter-houses and indecencies without end on which our life is founded are huddled out of sight.’

In 1916, aged in his mid-20s, Binks published a sermon titled When War Ceases: or The World’s Greatest ‘Growing Pain’. It framed battlefield carnage as one step along a path to ‘the great panoramic scene of the future — a veritable millennium — a kingdom of heaven upon earth’. Rejecting the view of ‘puny pessimists’, he saw this time of violence as crucial to progress and national glory, part of a divine plan beyond human understanding.

With the patter that he would eventually apply to his self-help business and work in advertising, Binks offered a predictable prescription: ‘take the attitude of cheeriness, always looking on the bright side, rather than the blue, determined to hold yourself in an optimistic, never-down-in-the-mouth, but courage-always-up attitude of mind and heart, through faith in the Infinite Source of Life and power which is back of all.’

History shows that World War I did not usher in the golden age that Binks predicted. But it casts him as a forebear in an enduring culture of advice, a member of a small army of positivity pundits who continue to spread the word of personal responsibility and inspiration today.

Dr Alexandra Roginski was the Library’s 2021 CH Currey Fellow.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2022.