The seventeenth-century flagship of the Dutch East India Company, the Batavia, was a glorious vessel, a symbol of wealth and power. It was not, however, invincible. Two letters recently added to the Library’s collection detail how the ship succumbed to the sea on its maiden voyage and the horror that followed.

The Batavia set sail from the Dutch port of Texel on 27 October 1628 in a fleet headed for the city that shared its name (now the Indonesian capital, Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. On board were more than 300 sailors, soldiers and civilians, as well as silver coins and other supplies for the colonial city. Bad weather saw the Batavia separated from the other ships, forcing the crew to face the Indian Ocean alone. A solo crossing was risky, but not everyone was unhappy with the turn of events.

The commander of the fleet, Francisco Pelsaert, was on board the Batavia alongside the ship’s captain, Ariaen Jacobsz. The two men disliked each other and the friction between them intensified when Jeronimus Cornelisz, Pelsaert’s deputy, offered his loyalty to Jacobsz and joined him in plotting mutiny.

Then, on 4 June 1629, the Batavia was sliced open on the Morning Reef, just off the coast of Western Australia. If Pelsaert had simply been deposed, the incident would have generated only a short paragraph in maritime history. Instead, Jacobsz and Cornelisz ensured that one of the first ships to be wrecked in Australian waters came to be remembered not just as a terrible accident but also as one of the bloodiest and most sadistic mutinies on record.

About 40 passengers drowned as the Batavia sank, the survivors making their way to the nearby Houtman Abrolhos Islands. With more survivors than supplies to keep them alive, Pelsaert made the desperate decision to take the ship’s longboat and finish the journey to the Dutch East Indies. A crew of 48 men, including Jacobsz, took 33 days to sail almost 3000 kilometres. Once in Batavia, Jacobsz was arrested for negligence. It then took a week to prepare another ship, the Sardam, so that Pelsaert could embark on a rescue mission.

Cornelisz, meanwhile, had taken command of those left behind. A disgraced pharmacist-turned- merchant, he disposed of anyone he saw as a threat to his control, or who would consume limited resources he needed for himself and his supporters. There was no mercy for anyone — military or civilian; man, woman or child — who might question him. More than 100 people were drowned or butchered on his orders. Some of the women were spared, only to be raped repeatedly by the leader and his men.

Several terrifying skirmishes broke out between the men fighting for Cornelisz and a group led by Wiebbe Hayes, who stood up to the mutineers. Cornelisz was eventually captured, but the risk of being overrun by his followers remained. Then, on 17 September, 63 days after the Sardam had headed south, Pelsaert returned to what is now known as Batavia’s Graveyard.

The reprisals for the crimes committed were swift and absolute. The worst of the mutineers had their right hands chopped off and were hanged on 2 October 1629. Cornelisz’s hanging was especially bloody: both of his hands were amputated before he was strung up. Two of his men, Wouter Loos and Jan Pelgrom de Bye, were abandoned on the Australian mainland, becoming the first Europeans to live on the continent. The rest of the mutinous gang was transported on the Sardam to Batavia for trial and punishment. When Pelsaert finally made it back there on 5 December 1629, he had with him only a third of those who had left the Netherlands the year before.

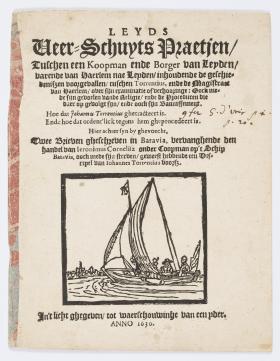

Two letters written in 1629 — and bound within a small book recently acquired by the Library — offer more details of the violence that unfolded on a set of inhospitable islands north-west of Geraldton. The book, a second edition from 1630 of a text that first appeared in 1628, is titled Leyds veer-schuyts praetjen or ‘Leyden Ferry-boat Gossip between a Merchant and a Citizen of Leyden’. It focuses on the talented painter Johannes van der Beeck, who rejected the social standards of his day and was accused of blasphemy, heresy and Satanism. It is widely believed van der Beeck influenced Cornelisz.

Batavia expert Mike Dash believes the authors of these accounts are Cornelisz Jansz, who fought alongside Hayes from West Wallabi Island to resist the mutineers, and Claes Gerritz, who sailed in the longboat as a member of Pelsaert’s crew. These documents are ‘made public as a warning to everyone’.

The two first-hand accounts pre-date Pelsaert’s own report, Ongeluckige voyagie or ‘Unhappy Voyage’, which was not published until 1647, more than 15 years after his death. A gory tale of victims and villains, it includes summaries of the confessions extracted from the mutineers under torture. The book became one of the world’s first true crime bestsellers, going into nine editions, and is the standard source for the storytellers who have retold this shocking tale for almost four centuries.

Dr Rachel Franks is the Library’s Coordinator, Scholarship. Her biography of Robert ‘Nosey Bob’ Howard will be published by NewSouth in 2022.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2021.