Since Australia’s colonisation, the islands above us and to our north-east have been places of wealth, subjects of study, playgrounds and battlefields. Many Australians have personal and familial links to the region. Governments, churches, private organisations and individuals have given vast amounts of monetary and in-kind assistance to Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and elsewhere. Footballers with Pacific heritage have become sporting heroes. And yet pundits constantly lament that Australians know little about the Pacific, and only the occasional natural disaster or political upheaval interrupts our normal news coverage.

Part of the answer to that conundrum lies in how we came to see ourselves over the past two centuries. For decades before and after Federation, white Australians looked to Britain as the motherland. Later, in the twentieth century, another ‘white’ country, the United States, was embraced as a big cousin. Pacific Islanders and Asians were the foils against which many Australians identified themselves.

This national image was honed by stories from the interior. The forests, rivers, pastures and deserts of Australia’s great expanses were the crucibles of a national type — shearers, farmers and drovers (and occasionally their wives). CEW Bean’s strapping Anzacs were the products of that wide brown land, and today they have been joined in the ranks of quintessential Australianness by hardworking suburban ‘mums and dads’.

Modern Australia clearly sat within but apart from its region, but exactly how did its white citizens distinguish themselves from those around them? During my 2019 CH Currey Fellowship at the State Library, I looked at the period between 1870 to 1970, a century in which Australians asserted their presence commercially, militarily and culturally in their region. Those years followed on directly from the period examined by Bernard Smith in his two magisterial studies of the Pacific’s impact on European art and science, European Vision and the South Pacific and Imagining the Pacific. It was from the latter that I took the Fellowship title, ‘Reimagining the Pacific’.

Similarly, the first matter of business for the new Australasian Geographical Society (later prefixed by Royal) in 1883 was organising an expedition to New Guinea to collect evidence to support its annexation by Britain in the face of German interests. The Society’s correspondence, held by the Library, includes letters from those eager to participate in the expedition. One particularly illuminating handwritten note came from Richard Searle, formerly of the Natal Mounted Police, who was keen to punish ‘natives’ for recent violent encounters with the advance guard of colonisation. ‘My age is 24 …’ he wrote. ‘I can ride well, dismount quickly and fire a good shot at moving objects’. Those ‘objects’ presumably included fleeing locals.

In the event, Searle was not selected for the Society’s 1885 expedition. Although the venture was not particularly successful — and was, for a time, feared lost on the Fly River — it didn’t dampen interest in the territory. In 1887 Britain somewhat reluctantly annexed the south-eastern part of the main island, which was named Papua, leaving the north-east to the Germans — much to the annoyance of Australian colonists.

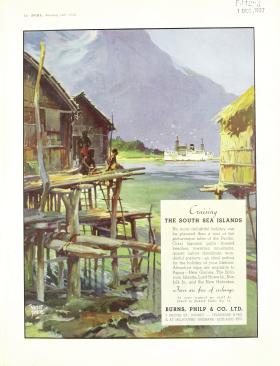

Assisted by the maritime services of the Australasian United Steam Navigation Co, Burns Philp and others, white Australians pursued commercial, intellectual and recreational interests in the region. The Handbook of Information, produced in Brisbane in 1894–95 by the British India and Queensland Agency Co Ltd, advised prospective travellers that steamers plied the east coast fortnightly from Sydney to Noumea and Fiji, and that each month two services carried mail between Cooktown and ‘all ports’ on the New Guinea coast from Samarai to Mabudawan ‘The knowledge of [that] country’, the handbook warned, ‘is still very incomplete in many particulars, as its inhabitants are only just emerging from a state of barbarism.’

Alongside those expected references to ‘barbarism’, I had hoped to find examples of empathy and references to a ‘shared humanity’, correctives to the dominant narratives of colonial arrogance. One of the most heartening of those emerged from the shelves of the Dixson collection. Caroline David was a teacher and the wife of the renowned Australian-based geologist Tannant William Edgeworth David, with whom she travelled to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands, now Tuvalu, in 1897. Edgeworth David’s aim was to prove or disprove Charles Darwin’s theory on the formation of coral reefs.

Caroline’s handsome 1899 book about the trip, Funafuti or Three Months on a Coral Island: An Unscientific Account of a Scientific Expedition, is wonderfully wry and humane. ‘The map labelled the islands British by putting a pink line under the name … if the black people kill and eat us, we shall be avenged!’ she writes. ‘We found afterwards that the Ellice Islanders hadn’t the faintest desire to kill and eat us; on the contrary, they were quite as civilised as most white folks …’ Caroline was customarily adopted as a daughter by a woman called Tufaina: ‘she told me that I was good, that she loved me, that she was my mother. I thanked her, said that I loved and respected her and was proud to be her daughter.’

I worked my way chronologically through these papers, ending with the postwar diaries, lecture notes and publications of James McAuley. That Australian man of letters is best remembered for his role in the Ern Malley affair, the literary hoax that aimed to torpedo the pretentions of modernism. Less appreciated is McAuley’s career as an educator and commentator on Australia’s role in Papua and New Guinea.

In the years after the Second World War, McAuley lectured at the Australian School of Pacific Administration and wrote sensitively about the territories in periodicals including South Pacific. He argued for the incorporation of Papua and New Guinea into Australia at a time when race-based immigration law still precluded easy travel from the former to the latter. His time there also influenced his politics and philosophy: he converted to Catholicism after meeting French missionaries, and became a fierce critic of the modern secular liberalism that elevated the individual over the community, the rational over tradition and faith.

After leaving the Australian School of Pacific Administration to take up an academic position in 1961, McAuley described with regret and foreboding ‘the great drama of the disintegration of traditional cultures’ that put into relief ‘every question about the nature of man and society’. It was a profound expression of empathy and recognition that bridged what many still regarded as a cultural chasm. The conservative James McAuley was able to find a common humanity in the Pacific where so many other Australians still saw difference.

Ian Hoskins was the State Library’s 2019 CH Currey Fellow. His latest book Australia and the Pacific (NewSouth Publishing, June 2021) is available to purchase from the Library Shop.

Maps of the Pacific is a free exhibition at the Library opening 13 November 2021.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2021.