I was strolling along St Kilda Esplanade one afternoon last autumn with the magnificently moustachioed tour guide and photographer Daniel Bornstein when Bornstein revealed to me that he was a shantyman.

I pointed to a colourful container ship gliding through Port Phillip Bay.

‘Does that make you want to go hey ho?’ I asked.

‘I’m a shantyman,’ he replied. ‘Everything makes me want to go hey ho ’

I had never heard the word ‘shantyman’ before. I had no idea that shanty singing was even a thing. I began to investigate further. Then came ‘Wellerman’.

‘Soon May the Wellerman Come’, now known universally as ‘Wellerman’, is a nineteenth-century New Zealand whaling song that went viral on TikTok, a phenomenally popular social-networking service that allows any user to post their own brief musical (or non-musical) performances to every laptop, iPad and smartphone on the planet. With TikTok’s duet function, bedroom balladeers can record themselves singing along with the original artist’s — or anyone else’s — version of a song, and add depth, effects or instrumentation.

A version of ‘Wellerman’ by the little-known UK folk group The Longest Johns seemed to manifest the zeitgeist in January this year, with its mournful tale of frustrated expectation at a time when life seemed locked in stasis all over the world — except, oddly, New Zealand. It sparked thousands of tributes, imitations and augmentations. A subsequent recording of ‘Wellerman’ by Scottish folksinger and former postie Nathan Evans reached number one in the UK dance charts. A corporate neologism, ‘ShantyTok’, was coined to describe the sudden, unprecedented interest in sea shanties on social media.

I ask Walters if there was any initial resistance among shantymen to the involvement of the gender that was traditionally less likely to wear a beard?

‘Not really,’ she says. ‘Back in the old days, a lot of women chose not to go near shanty sessions because they were peopled by big blokes with beards and big voices, and a lot of girls with small voices didn’t particularly like that. Also, a lot of the songs could be seen to be sexist — catalogues of girls in every port and … proclivities.’

Walters’ band — then known as the Roaring Forties — welcomed the replica First Fleet into Sydney Harbour for the 1988 bicentennial celebrations and performed regularly at the Australian National Maritime Museum (something of a haven for shanty buffs). But Walters didn’t see much new blood come into scene through the nineties and the noughties. ‘At folk festivals, we would sometimes try and avoid the word “shanty” and make sure there was just a “chorus session” towards the end of the evening,’ she says.

However, in 2014, a friend of Walters suggested they visit the Monday-night shanty session at the Dock, a Redfern small bar where a piano keyboard adheres to the ceiling and even the lowly wall-mounted moosehead sports a colourful kerchief.

‘I was totally blown away,’ says Walters, ‘because the people who were there were all under 30! Me and my mates rock along and pull up the average ages considerably.’

At the Dock, the Redfern Shanty Club belted out traditional favourites such as ‘South Australia’ and ‘The Whale’ with a vigour that had not recently been associated with the form. The club handed out song sheets and taught the tunes to newcomers each week. The very fact that there were any newcomers seemed to show this might be a sensible approach.

In Melbourne, Bornstein and Joe Hillel, the Grubby Urchins, had adopted a similar method when they came together in 2018. Although there was regular shanty singing on board the replica tall ship Enterprize in Port Phillip Bay, there was no longer much of a scene on land until the Grubby Urchins pioneered a shanty night at the Brothers Public House in Fitzroy. ‘The first session was a full house,’ says Bornstein, ‘and, after that, they just kept growing and growing. And we did nothing in terms of spreading the word. It just kind of grew itself.’

There seemed to be a large and untapped appetite for communal singing, and shanties made for ideal fodder as they were easy to learn, simple to sing and — by their origins — designed for people to join in.

Many people in shantyworld are keen to share their definition of a shanty, and to point out that ‘Wellerman’, technically speaking, is not one.

Classically, shanties were sung to help synchronise labour on board large ships. In the dynamic days of nineteenth-century packet runs, clipper ships offered regular, scheduled maritime mail services for the first time. Sailing ships, which were largely driven by manpower, had to work like machines.

On the heavy vessels, the biggest task was to raise an anchor that might weigh tens of tons. A small crew could only succeed using concerted, rhythmic muscle power and harmonised movement. There were long haul/long drag shanties and short haul shanties to complement various nautical duties. The ship’s shantyman led the singing but played no other part in the job. He had to incorporate different songs, invent new verses, and bawl out his lungs for up to six hours at a time.

Shanty-motivated seamen worked faster and felt more involved. The singing raised their spirits. ‘Having a shantyman was an economic imperative, in a sense,’ says Walters. There was a saying that ‘a good shantyman was worth 10 crew’.

It is difficult to point to a particularly Australian shanty tradition, as merchant navies visited ports from New York to Bombay and Hong Kong to Hobart, learning and adapting local songs. Most shanties have many versions that reference different people and places. A number have quite sinister origins in songs sung on slave plantations to set the pace of cotton picking. ‘Wellerman’, says Bornstein, was probably written by an Australian. ‘South Australia’, on the other hand, probably was not.

Many of the songs regarded by laypeople as sea shanties are actually sea songs, or maritime ballads. A polite way to incorporate them into the canon is to call them ‘fo’c’sle shanties’, as they might have been sung on board ship by sailors in the forecastle, resting between watches.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, many shipboard tasks had become mechanised. Old sailors might still sing shanties for sentimental reasons, but there was no longer much need to chant in time to a task. Enthusiasts became concerned to preserve the songs, anticipating a disappearing form. Percy Grainger, Australia’s foremost modern composer, collected sea shanties and arranged them for piano forte. He tended to clean up the bawdier lyrics, so that many early commercial recordings are polished, stylised and sanitised, with operatic baritones and hammy harmonies. Today, however, shantymen and women tend to act rougher than they really are, rather than more refined.

‘A lot of people take on a character when they sing sea shanties,’ says Bornstein. ‘They’re very evocative words and you really feel like they come out of the great nautical age.’

When a customer walks into the bar at the Peg Leg Inn in Pyrmont, the bartender calls out, ‘Ahoy!’

Many customers respond, ‘Ahoy!’

To which the bartender replies, ‘Ahoy!’

Given a bloody-minded customer and a determined bartender, the exchange of ‘ahoys’ might go on all night.

The Peg Leg Inn is a pirate-themed pub where local band the Mutineers used to perform sea songs and shanties. Alex Gaffikin, head of interpretation and design at the Maritime Museum, plays in the Mutineers with her partner, Stephen Gapps, a curator at the museum. Like Bornstein, she treasures the arcane language of shanties.

‘In “Spanish Ladies” there’s a wonderful line, “Haul up your clugarnets!”’ says Gaffikin. ‘I have no idea what a clugarnet is, but there’s the absolute fun of singing this sort of sailing gibberish.’

‘There’s an element of play,’ says Bornstein. ‘It’s not so much that people throw on a costume and say, “I’m now Black Bart the Pirate.” When people get up, they’ll sing with a sort of accent. A lot of the time, people don’t even realise they’re doing it.’

Shanty people strive for various degrees of maritime-musical authenticity.

‘Stephen can be a bit of a purist,’ says Gaffikin. ‘He tries to get us to dress as if we were eighteenth or nineteenth century sailors. It’s actually quite hard to play instruments in a typical pirate costume. I play the guitar sometimes, and big, floppy sleeves don’t work that well.’

Not long ago the Peg Leg Inn was a brothel, where the women wore clugarnets. Probably. Its rebirth as a (pre-Covid) venue for shanties signifies a quest for an appropriate atmosphere.

Last year, the Grubby Urchins released Futtocks in the Fo’c’sle, an album of 25 unaccompanied sea shanties arranged in three-part harmony and recorded live on the Enterprize. ‘This presented an unbelievable technical challenge,’ says Bornstein. ‘The creaking of the ship was fine — we wanted a bit of that in the background — but the ship was docked underneath the Bolte Bridge, so we got more traffic noise than ship creaking anyway. And keeping time — when the ship was keeping different time — was really difficult.’

There would seem to be solid reasons why most musicians do not board ships to record their music, just as most navies do not sail off to war in recording studios. ‘But we’re pretty happy with how it sounds,’ says Bornstein.

The tension between traditionalists and modernists has always animated debate among shanty people. Walters says she wrangled a place for the Redfern Shanty Crew on the bill at the National Folk Festival, but when they sang, ‘The folkies were all sitting at the back going, “That’s not how it goes!” and “You don’t have to teach us the words!”’

Like all the other shantymen and women, Walters loves to sing on board tall ships such as the replica James Craig, which is moored outside the Maritime Museum. ‘But the atmosphere was so boring compared to what you get up at the Dock,’ she says. ‘Up at the Dock it was so… sensuous.’

It also seems likely that a broader debate will open up about the lyrics and origins of certain shanties. The bawdiness that once disgusted Victorians is unlikely to offend anyone today, but racist epithets have been quietly removed from some of the rhymes. Then there is the fact that many shanties could be regarded as appropriated slave songs. ‘There’s a feeling that, if you haven’t had the cultural experience, then you wouldn’t be singing the song,’ says Walters. ‘That would cut out 90 per cent of my repertoire. I haven’t been down a coal mine. I haven’t been whaling. But I do think the stories should be told.’

If she has never been whaling or coalmining, what does she do for living?

‘I’m a librarian!’ she says, laughing.

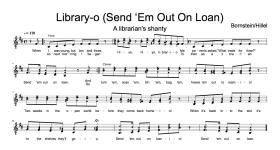

By an extraordinary coincidence, the State Library had already commissioned the world’s first ‘library shanty’ from the Grubby Urchins. You can listen to an original ‘library shanty’ by the Grubby Urchins and read the lyrics here.

The Grubby Urchins - Library - O

I dreamed that evening, as I slept

Of where the books are neatly kept

I dreamed of shelves ten fathoms high

Where books from every land do lie

I dreamed of bins and stacks and shelves

Where readers go and help their'selves

I dreamed of books in tidy rows

From ancient verse to modern prose

The lib'ry life is free from woes

The chief concern is where books goes

So growl ye may, but read ye must

You talk too loud, your head they'll bust

If friendly staff is what ye seeks

Bring back yer' books within two weeks

Be warned, when on a reading spree

Late books incur a nom'nal fee

The lib'ry trade takes stalwart guts

For every year brings gov'ment cuts

They say that borr'wing books is hard

For those without a lib'ry card

And when the lending time is through

It's back ye'II mosey to renew

And when the readin's good and done

It's back to pick another one

•N.b., the suffix 'i-o' is sung 'aye-oh' (as if to rhyme with 'sky-oh?, in proper seafarer's tradition

Hi-yo, hi-yo, librar-i-o!

Dr Mark Dapin is an author and journalist whose history books include The Nashos’ War, Australia’s Vietnam: Myth vs History and Jewish Anzacs.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2021.