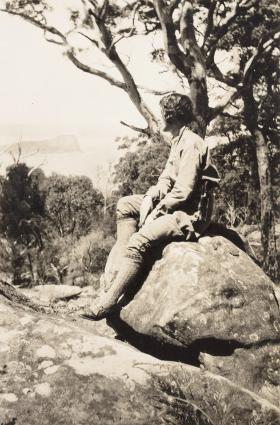

With a bob-styled haircut, drill riding suit, knitted knee-hose and a hunting knife strapped firmly to her waist, Ella McFadyen cut a striking figure. A lifelong naturalist and energetic bushwalker, her outfit was well-worn. This was a woman who invited leaf-tailed geckos into her tent at night and could pin down a snake with her foot, before swiftly severing its head.

Softly spoken and sturdy in appearance, Ella was known for her firm convictions and lofty ideals. ‘Ella McFadyen sings with the wind as she moves along’, observed writer Zora Cross. The children’s book reviewer Eve Pownall described her writing as ‘zestful’ with a ‘talk-as-you go-manner’ where the ‘improbable seems the only possible thing’.

Ella’s relationship with nature began during her childhood in Sydney. The second eldest of six, she grew up on a small property in Five Dock. Just beyond a paddock full of buttercups stood the local public school, but Ella’s mother chose instead to home school her children. Troubled by ‘ghosts inside the house’, Ella often buried herself in books and poetry or escaped outdoors. She wandered out into the paddocks and gardens around the family home with her ‘jolly little’ camera or visited the museum to sketch birds.

Sometime after Ella turned 15, the McFadyens moved to Noonan’s Point on Brisbane Water. It was there, despite the vocal disapproval of her mother, that Ella began to publish her verse. Within a few years she had emerged on the Sydney literary scene as a prolific and versatile writer, her name appearing alongside those of Zora Cross, Dorothea Mackellar, Nina Murdoch and other young talent. ‘Her career will be worth watching,’ wrote a reviewer of her first collection of verse, Outland Born, in 1911.

Publishing under her own name as well as an assortment of pen-names, Ella wrote art and craft articles, travelogues, children’s stories, local history, literary criticism, essays, poetry and songs. Later she would emerge as a fierce manuscript reviewer for the publisher Angus & Robertson.

Some of Ella’s poems had an echo of Kipling and the ‘Old Country’. Others blended the traditions of the bush poets with those of English and Scottish balladists. She wrote with careful attention to melody, and her early poems were admired for their technical skill, imaginative imagery and use of Australian placenames. Recognising the lyric quality of Ella’s verse, the Sydney critic and editor Bertram Stevens encouraged her to write romance. She did for a time, but soon returned to children’s stories and nature writing.

From red octopuses to frogs, water beetles to fungi, no living thing was too small or strange for Ella. Much of her nature writing was infused with homely images. She sat under the ‘the kindly Inn of the Banksia tree’, basked in the ‘Woy Woy lights’, kept the company of ‘Friend Crow, the black pirate of the bird world’, and once had a marriage proposal from a mopoke owl. It was not uncommon for fairies and other fantastic creatures to appear in her verse. Like her brother Clifford, she was a keen collector of folklore and local history.

Together with her poetic sensibilities, Ella’s hawk-like attention to detail enabled her to turn the most casual observations into captivating storytelling. This talent also contributed to her success as a children’s page editor for the Sydney Mail from 1920 to 1938. In this role, under the pen-name ‘Cinderella’, she combined her love of nature, folklore and poetry.

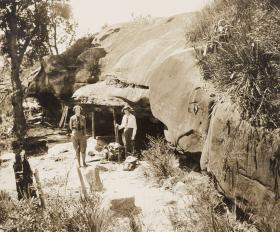

The children’s page quickly expanded beyond the paper’s margins. Ten years after her first column as ‘Cinderella’, encouraged by a wider urban middle-class bushwalking movement as well as her Scottish Highlander ancestors’ reputation as walkers, Ella led a small party of young women — Flora McLeod, Jean Bransdon and Jean Urquart — on a three-day bushwalk in the Southern Highlands.

They called themselves the Boomerang Club. Modestly dressed in tweed walking coats, strong brogues, felt hats, each with a haversack on their back, the party of four met at Moss Vale Station after midnight. There they enjoyed a meat pie, a spoonful of green peas and a pot of tea in the refreshment room before setting out at first light.

At Fitzroy Falls they invented the ‘celebrated Fitzroy tart’ — a heavily buttered wheatmeal biscuit topped with chopped pineapple — before making their way over Barrengarry Mountain, through Kangaroo Valley and up to Cambewarra. Along the way they lodged with local families and were aided by a mischievous young boy, two kindly Russian farmers and a mounted policeman.

The journey from Moss Vale to Nowra was the start of a new chapter for Ella — and perhaps also for Flora and the two Jeans. They would spend many days adventuring in Nattai, Ku-ring-gai Chase, the Royal National Park, Lamington National Park, the Blue Mountains and the Warrumbungles, sometimes accompanied by young male bushwalkers. Alongside more leisurely walks, the Boomerang Club attempted long-distance walking records — once travelling 56 miles from Moss Vale to Berry in a single day.

It was during her early years as a bushwalker that Ella was sent her first pair of thorny dragon lizards, named Wendy and Marco Polo Junior. Over the next few years, Ella’s devotion to her little housemates, who could often be seen curled around her neck or clinging to her skirts, led to an affiliation with the Royal Zoological Society, Taronga Zoo and Sydney naturalists such as George Longley and Thistle Harris.

Although Wendy and Marco inspired several of Ella’s children’s stories, especially her third children’s book Dragons of the Never Never (1948), her nature study always maintained a scholarly dimension. Her contributions to magazines such as Wild Life and Walkabout, entwining poetry, Aboriginal legends and nature study, were illustrated with her own stunning photographs — in fact, the acclaimed British wildlife photographer Cherry Kearton considered Ella’s lizard photographs nothing short of ‘excellent’.

Aside from her juvenile correspondents and a small circle of close friends and family members, Ella was curiously removed from the Sydney literary scene. Though Mary Gilmore initially took her under her wing, Ella drifted away from the community of young writers and journalists after the Great War. She remained affiliated with several literary organisations, her address books in the Library’s collection peppered with the names of notable Australian editors, artists and writers, but the children’s page, and later her work as a manuscript reviewer, consumed most of her free time.

Like many women writers of the twentieth century, Ella’s legacy as a poet and naturalist remains largely invisible. Few today would recognise her face or her poetry. Her most recognised contribution to Australian literature and culture is her writing for children. As ‘Cinderella’, and later as a camp mother for the Junior Red Cross, she encouraged many children to persist with their writing, art and nature study. Among the thousands influenced by the fairy editor were the poets Judith Wright, Gina Ballantyne, Martin Haley, Betty Casey and Llywelyn Lucas. Writer and children’s literature advocate Maurice Saxby once saw Ella ‘glow with animation’ when surrounded by youngsters. ‘Something does rub off,’ he confessed.

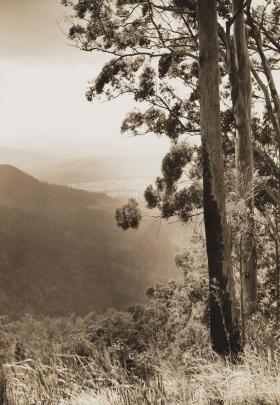

By the time of Ella’s death, the Sydney of her childhood had changed dramatically. In an interview with Hazel de Berg in 1972, four years before she died at the age of 88 in a nursing home in Lane Cove, Ella imagined a heaven among the gum trees, crowded with ‘little lizards and birds’. While her love of nature never led her to forsake city life — her favourite tree was a Moreton Bay Fig in Sydney’s Macquarie Place — a long life of writing, talking and walking about nature had urged her to trade the Christian faith of her parents for a ‘bush spiritualism’. Having gazed out at Lion Island from ‘Warm Rock’ and down into Numinbah Valley from the Macpherson Range, Ella McFadyen had already seen heaven on earth.

Emily Gallagher is a PhD candidate at the ANU’s School of History. Her research focuses on the history of children’s imaginations in Australia during the twentieth century.