Hannah Maclurcan — an antipodean version of the famous British cookbook author Isabella Beeton — wasn’t the first Australian to publish a cookbook with the ingredients and for the climate of this harsh southern land.

She was the first, however, to become bestselling author, household name, fashion icon, entrepreneur, society-page queen. And, in 1912, she may have been the first woman to become managing director of an Australian publicly listed company.

Through their ability to share their love of cooking with a mass audience (which, in Hannah’s time, was mainly female), both women also eclipsed their fathers. (Who today recalls that Nigella’s father was Margaret Thatcher’s Chancellor of the Exchequer?)

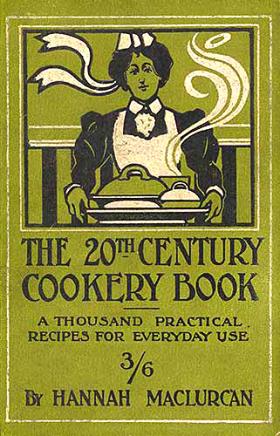

Hannah’s cookbooks will never sell as many copies as Nigella’s. Yet when she presented a copy of her second book, The 20th Century Cookery Book, to Queen Victoria in 1901 (designed for the British market with less kangaroo and more venison) she was already a publishing phenomenon.

Her first book, Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book, had been self-published in 1898 in Queensland, three decades after Mrs Beeton’s tome had its first Australian edition. Unlike the Englishwoman’s volume, which assumed that readers had well-stocked stores nearby, her book was subtitled: ‘A Collection of Practical Recipes Suitable for Australia’.

But when Hannah sailed to Sydney and Melbourne in search of a publisher, she met with no success.

‘In fact, she was advised to save her money by burning her manuscript,’ says Karen Bates, who has charted Maclurcan’s life in Australian culinary history.

‘Undaunted, Hannah returned to Townsville, hired a local printer, set her own typeface and published 756 recipes which she had perfected cooking in hotel kitchens. The first edition of 2000 copies sold out within eight weeks. The second edition of 4000 had sold by Christmas.’

Reviewers praised Hannah for her ‘terse and plain language’, her ‘tasty, appetising and attractive’ dishes, and for producing ‘a cookery-book adapted to colonial resources’. The most quoted endorsement? ‘A foe to indigestion.’

It’s easy to lampoon her for her old-fashioned fare, but here’s a typical meal for 50 guests she served at the Queen’s Hotel in Townsville for the visit of the Governor-General,

Lord Lamington:

Starters: Oysters; beche-de-mer soup, boiled barramundi and oyster sauce, whiting fillet

Entree: Pate de foie gras, oyster patties, spatchcock

Joints: Roast sirloin beef and horse radish, roast saddle mutton and red currant jelly, boiled leg mutton and caper sauce, boiled round beef, tongue and ham

Poultry: Roast turkey and truffles, roast duckling and green peas, roast wild goose with port wine sauce

Savouries: Devilled prawns, anchovy canapés

Sweets: Trifle, tipsy cake, strawberry jelly, cheesecake, gooseberry fool

To finish: Crab a la Francoise, cheese soufflé, devilled almond, cheese straws, celery, Gorgonzola, lobster salad, fruits in season, preserved fruits and ‘ices’

So much for ‘foe to indigestion’!

‘Hannah realised you could build a hotel’s reputation by the quality of its food,’ says her great-grandson. ‘She learned that lesson long before she took over Sydney’s Wentworth Hotel, turning it into one of the finest elite hotels in the southern hemisphere.’

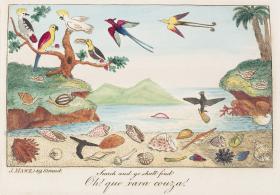

Take beche-de-mer soup.

‘The humble sea slug was a delicacy in China,’ Bates explains. ‘Hannah also experimented with seafood, tropical fruits and native plants mainly eaten by Indigenous locals.’

Born in October 1860 near Hill End in New South Wales, Hannah was the product of Australia’s gold rushes.

Her London-born father, Jacob Aaron Phillips, understood that the secret to becoming rich in mining towns was not by toiling underground but by becoming a shopkeeper or a hotelier. Phillips moved to Queensland, anticipating where hopeless dreamers would stake their next claim.

Hannah was the fourth child of Phillips and his first wife, Susan Moses, who died when her daughter was six. Always street-smart, Hannah was so proficient as a hotelier that at 15 she was appointed manager of the Osbourne Hotel at Sandgate, a coastal resort on the outskirts of Brisbane.

Her first marriage in 1880, to an English-born ne’er-do-well, left her the single mother of two young daughters. In 1887, she married Donald Maclurcan, a master mariner who fathered her youngest two children. Donald’s name might have been registered as the hotel licencee, but everyone knew Hannah was the boss.

Thanks to her cookbook (18 editions in 30 years) Hannah took her biggest gamble in 1901, leasing Sydney’s Wentworth Hotel, then little more than a glorified boarding house. After Donald died in 1903, Hannah transformed the Wentworth into arguably the finest hotel south of the Equator. Her innovations were legendary, particularly once she became managing director of the limited company set up in 1912 to administer the Wentworth and acquire the freehold.

She introduced the New York-style a la carte menu to Australia, freeing diners from staid hotel sittings and enabling them to have their personal selections cooked to order ‘between 11am and 11pm’.

She purchased neighbouring land to create an elegant al fresco dining area where ladies who lunched could be seen in all their fashionable glory, before converting the site into the Wentworth Ballroom (where the Prince of Wales danced at its official opening in 1920).

She added extra storeys and installed one of the first lifts in Australia (the Sydney Morning Herald ran a story on this technological marvel). She also launched the Wentworth Magazine, a glossy periodical with contributions from fashionable painters and authors, theatre reviews for those planning an overnight stay, and bridal fashions.

Sadly, her entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography is sour. Though acknowledging she was one of the first hoteliers in Australia to add a 400-vehicle car park with petrol pump as well as an outlet selling lingerie, hosiery and those ‘toiletry trifles a man may have forgotten to pack’, the entry dwells on Hannah’s ‘shameless’ courting of celebrities and ‘the stodgy depths to which Australian middle-class cooking had descended’ by the 1920s.

Naturally, it includes her final marriage in 1931 to a third Englishman, Robert Lee, a decade her junior, who her great- grandson describes as a scoundrel. ‘When she died in 1936 the family had a devil of a job dealing with him. Fortunately, he died not long after her.’

Hannah’s Wentworth is no more, but her cookbooks are a wonderful reminder of an era when the perfect recipe for a fricassee of sheep’s brains was as valuable as a lesson in how to serve an acceptable cucumber sandwich (‘First cut the bread very fine’).

Ultimately, Hannah’s legacy is the bold step she took in 1912, ‘taking Sydney’s finest hotel to the stockmarket, and being appointed managing director with plans to expand it to even greater heights,’ John Maclurcan says. ‘Isn’t it amazing she achieved that two years before World War I?’

Steve Meacham is a Sydney-based freelance writer.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2021.