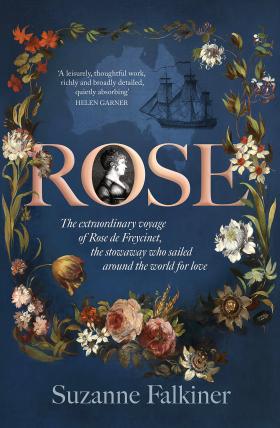

THE WRITER: SUZANNE FALKINER ON THE JOURNAL OF ROSE DE FREYCINET

Inscribed in even, economical lines with a quill pen in black ink of variously fading intensities, Rose de Freycinet’s journal, in three flimsy blue-paper-covered notebooks, comprises some 120 pages of dated entries: some neat, others scarred with crossings-out and annotations, others marked with blots and irregularities that might have resulted from writing in a ship’s cramped and heaving cabin. To the unhabituated eye, many of these closely written leaves seem almost unintelligible, with the stylised letters — m’s and n’s and u’s and w’s — merging indistinguishably into each other. The first page contains a dedication. The entire work had been written due to a promise to a childhood friend, in part as a gift in case Rose did not survive the next three dangerous years at sea.

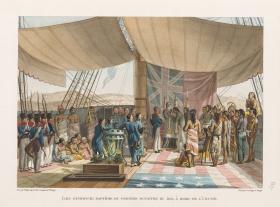

Rose, unable to bear being parted from her new husband, French naval officer Louis de Freycinet, when he embarked on an expedition of scientific discovery to the South Seas, had hidden herself in his cabin on the night before he sailed, emerging only when the ship was beyond French waters. It was a plot that Jane Austen herself might have contrived: a lonely young naval officer of good family returns from the Napoleonic Wars to find himself a bride in Rose, the 19-year-old daughter of a widowed and impoverished schoolteacher.

Louis, a skilled cartographer who had sailed with explorer Nicolas Baudin, had made his mark in history by becoming the first to publish a full map of the Australian coastline. Rose would make hers by being the first woman to circumnavigate the world and leave a written account of her journey.

Louis, however, in his exhaustive record of his second expedition, would make no mention of Rose’s presence, beyond an enigmatic notation that he had named a remote atoll in Western Samoa ‘for someone extremely dear to me’. Neither would any of his officers: according to French officialdom and naval regulations, she did not exist. So who was Rose? This woman about whom little was known except the date and place of her birth, and that her mother’s first name was probably Jeanne?

Rose’s private journal, given to her childhood friend Caroline de Nanteuil in 1820, was returned to the Freycinet family by a descendant in 1913 and kept in the library of the Château de l’Âge, near the town of Chabanais in Charente, for several generations. An abridged transcription appeared in Paris in around 1927. An English translation by Mauritian scholar Marc Serge Rivière, taken from the published French version, appeared in Australia in 1996.

I had found this translated edition curiously bland at first. Later I would realise that the text had passed through the hands of several male editors who, in small but significant ways, had bowdlerised it.

Meanwhile, I learned, from the 1960s the Freycinet family archives had been dispersed by international auction into private collections all over the world. From among this wealth of historical documents, hand-drawn maps, drawings and painted illustrations, Rose’s manuscript, ‘Journal particulier de Rose pour Caroline’, September 1817–October 1820, was acquired by the State Library of NSW in 2013, and a letter book — Louis’s transcription of Rose’s shipboard letters to her mother — in 2014.

Now, for the first time these documents became available to the general public. Other family papers and letters followed in 2021.

Serendipitously, I discovered, Meredith Lawn, the archivist in charge of cataloguing the Freycinet collection was as entranced by Rose’s story as I was, and facilitated my access to the collection and kept me informed of tantalising new acquisitions.

When I was a very small child, I was bewitched by a book called The Magic Faraway Tree. In it, the English writer Enid Blyton describes a stalwart band of British children who discover an enchanted forest with a tree so tall that it touches the clouds. From its highest branches the children can climb into a series of magical worlds, sometimes pleasant, sometimes perilous, and different on every visit. Each time, the children must return from their explorations and reach the cloud-hole before the clouds move on, or else find themselves trapped in that particular domain until it revolves around again.

Sometimes it seems to me that for Rose de Freycinet, the magic tree was a wooden ship with three tall masts and white wings spread like a bird’s, bringing her to a succession of strange and unknown lands as the Earth rotated under its hull: a journey waiting to be rediscovered and relived in the dry paper archives of the State Library of NSW.

Suzanne Falkiner’s most recent book is Rose, an account of Rose de Freycinet’s voyage, published by HarperCollins Australia in 2022.

THE ARCHIVIST: MEREDITH LAWN ON THE FREYCINET FAMILY

In mid-2019, I had the privilege of cataloguing a large collection of documents from the Freycinet family archive purchased by the Library from Hordern House Rare Books. The collection consisted of some 300 manuscripts in French from the early nineteenth century, some in elegant, legible handwriting and others in an almost indecipherable scrawl. Cataloguing it over many weeks, the collection transported me to a different time and place. I was able to touch the very paper that both the writer and recipient had held in their hands 200 years before me. The story of the Freycinet family was revealed to me like a gripping novel, set in the same period as Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.

It captivated me more than any other collection I have catalogued. Covering four generations, I researched the family tree to understand all the connections. I was drawn into the heart of the family and felt that I almost knew the family members personally. Élisabeth de Freycinet would write letters to her son Henri and then hand the pen over to her husband to finish off the page (Je laisse la plume à ton père).

As parents, they were concerned for the careers and promotion of their adult sons and were clearly fond of their daughters-in-law.

I saw Henri de Freycinet’s handwriting change from his elegant right-handed script to shaky attempts to sign documents with his left hand a day after losing his right arm in a sea battle with a British warship. I read about Rose’s life in Paris after the Uranie voyage, her joy in being entrusted with the care of her young nephew Lodoïx, son of Henri and Clémentine, and then her sadness at having to hand him back to his parents three years later, which perhaps exacerbated the melancholy and poor health of her final years.

Louis de Freycinet’s personality was revealed through the papers as someone who was extremely conscientious and hard-working, who often felt misunderstood and unappreciated. The document that gave me the greatest insight into Louis’s thoughts and feelings was a six-page manuscript that he intended to be published as an epilogue to his Uranie voyage account. In these heartfelt pages, Louis recorded the hardships he endured in completing the work and the lack of support from the French authorities.

The Library purchased a further 47 documents from the Freycinet family archive when they came onto the market through Maggs Bros in London in late 2020. I also catalogued these. This collection added many significant documents to our holdings: Louis’s 1816 proposal for the Uranie voyage and letters from his parents to Henri, in which they transcribed precious letters received from Rose and Louis on their voyage, including their account of the shipwreck.

Now reunited at the State Library with the journal and transcribed letters of Rose, which also came from the Freycinet family archive, these two additional collections are a source of much fresh information about the two Freycinet brothers and Rose, and the way their lives intersected with the early years of European settlement in Australia. Knowing that Suzanne Falkiner was able to use the material in her book only increased my enjoyment. We exchanged information to our mutual benefit, and Suzanne even shared some draft chapters with me.

Well before I was assigned to catalogue the first Freycinet collection, my husband and I had booked a holiday to Provence and the Ardèche region in the south of France in September 2019. While working on the Freycinet collection, I saw letters sent from the family château at Freycinet. Searching online to find the location of the Château de Freycinet at Saulce-sur-Rhône, I discovered that it was not far from where we were intending to go. Using Street View, I could see the closed gates to the property, but it was impossible to see down the driveway and a thick row of trees along the street blocked any view of the château.

Meredith Lawn is a specialist librarian.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2022.