This coming October long weekend on the South Coast, around the Shoalhaven, the most anticipated event for Aboriginal people in NSW is happening: the 50th NSW Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout. Commonly known as the Koori Knockout, this huge gathering of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people will last for four amazing days. An estimated 30,000 people — players and spectators — will travel from all over the state for what is the largest rugby league knockout carnival anywhere in the world.

2022 will see seven different competitions: men’s, women’s and five junior divisions of boys and girls. Around 180 teams will compete, each with 25 players, totalling a whopping 4500 players representing up to 40 different Aboriginal communities from across NSW.

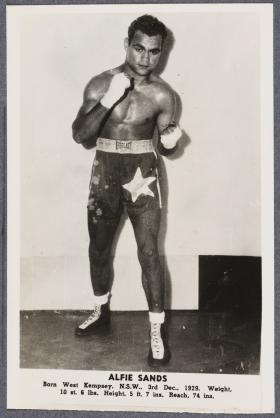

First held in 1971 at Camdenville Oval in St Peters in Sydney, the Knockout was initiated by six young Aboriginal men: Bill Kennedy, Bob Morgan, Danny Rose, Bob Smith, Victor Wright and the late George Jackson. They saw it as an opportunity to bring together Aboriginal players and highlight their abilities so that the talent scouts would see what they had been overlooking. Only Bruce ‘Larpa’ Stewart, who played for the Roosters, and Eric Simms, who played for the Rabbitohs, had managed to establish themselves as regular first-graders in the 1960s. The founding Knockout teams were La Perouse, Koorie United, Redfern All Blacks, Kempsey, Walgett, Moree and a combined Mt Druitt–South Coast team. The first Knockout winner was La Perouse.

I think this is why I’m so passionate about the Koori Knockout. I’m a Bidjigal man from La Perouse, the small community on the northern part of Botany Bay (Gamay). Rugby league and the Bay were all we had as kids growing up in La Pa. If you didn’t play footy, you watched it. La Perouse has produced some very successful athletes over the years, including rugby union’s Ella brothers, Mark, Glen and Gary, and their amazing sister Marcia, who became the first Indigenous Australian representative in international netball. Many Aboriginal players from La Perouse have made it into the NRL and have also played Knockout in the black and white La Perouse team colours.

I wasn’t that much of a player myself, although I have fond memories of captaining an under-19s La Perouse exhibition team in 1992 against a talented Moree Boomerangs team, one of our greatest rivals. I was fortunate to play alongside some future stars of the game, including Anthony Mundine, Wes Patten, Robbie Simpson and Matt Mitchell, father of Latrell, now star fullback for the South Sydney Rabbitohs. We were too good for the Boomerangs that day — one of my all-time favourite photos is me holding the winning shield.

These days, I’m the lead Knockout commentator for National Indigenous Television (NITV) and have been lucky enough to call the past 13 grand finals. It is easily the highlight of my year. As well as calling the Sunday and Monday of the event, I work on the KO App. In 2016, with my brother Mitchell Ross, head of the Indigenous-owned technology and office supplies company Muru Group, I created a score-keeping app to enable people on other grounds, and those not at the event, to follow each game live. Now approximately 11,000 people use the app, which includes interviews with attendees and players, as well as event updates.

NITV’s involvement since 2007 means that community members unable to attend the event can watch from the comfort of their homes. I was informed one year that many of our brothers and sisters in NSW jails are glued to the TV during Knockout. I can imagine their pride, watching their mob run out, hearing familiar names and wishing they could be there to see it up close.

Over the past 50 years, the Knockout has become a highly professional, widely recognised event. Many claim it is the best rugby league played anywhere, surpassing the NRL competition. I’ve heard it called ‘Koori Christmas’, or ‘a modern-day corroboree’, with people turning up from all over NSW to gather on the land of the previous year’s men’s-division winner.

The COVID pandemic saw a two-year hiatus, so 2019 winners the South Coast Black Cockatoos have had an agonising wait to host the big 50th anniversary event. The South Coast team defeated Griffith Three-Ways United in an impressive display, with a nice mix of experienced and talented young players. That year, the Black Cockatoos were a memorial team in honour of James Wellington, a regular player at Knockouts who passed away the previous year. Memorial teams are commonplace at Koori Knockouts and are a powerful way to honour the loss of a loved one linked to community. The South Coast Black Cockatoos were led by James’s brother Ben and managed by their sister Melissa. Ex-NRL star Dylan Farrell was also on the team, which included one of the many father-and-son combinations from across the competition — Jason Sullivan and his St George Illawarra Dragons son Jayden ‘Bud’ Sullivan. Bud Sullivan was the star of the show, the young halfback showing his skills with ball in hand and kicking goals in the strong breeze. The Griffith team wasn’t bad either, with the likes of Andrew Fifita and Nicho Hynes.

This year’s event, to be held across two grounds in Nowra and Bomaderry, will be the responsibility of Ben Wellington and Melissa Wellington, and their committee. In 2016, for the ‘Road to the KO’ YouTube series, I interviewed Associate Professor Heidi Norman, Koori Knockout historian and then-committee member for the Redfern All Blacks. I asked her about the cost of hosting an event. Her response was staggering: ‘$750,000 in cash and in-kind support’, she said, was required to host the 2016 event. A large event needs appropriate infrastructure — security, health and safety, sponsorship, volunteers and so on — not only to successfully manage 30,000 participants and attendees, but to comply with council regulations.

But there are financial benefits too. Local councils have estimated that the return for regional centres hosting the Knockout can be in the vicinity of several million dollars, even though most host communities just break even. So it is sad that some communities throughout NSW over the past 50 years have looked down on this extraordinary event. There have been incidents of racism, with cases of heavy-handed policing and hotels closing pools because they don’t want Aboriginal people to swim in them. In Nambucca Heads one year, shops were so fearful, they all closed. Often these same people, and their local newspapers, state post-event that crime went down in the period of the Knockout because the ‘troublemakers were busy’. Talk about backhanded compliments!

But host committees’ relationships with police and local businesses have improved, and the Knockout is being better received by non-Indigenous people. When non-Indigenous communities embrace the event, it not only creates a more enjoyable experience for Aboriginal people, but locals reap the financial benefits from thousands of people spending in their town. I remember a few years back, in Dubbo, a BBQ chicken and devon shortage was being reported. KFC even ran out of chicken. We do love our chicken and devon.

The Knockout’s main drawcard is obviously the players. One thing that stands out is the large number of professional NRL and NRLW players competing each year, such is their love for their mobs and their respective communities. They also show great loyalty, in spite of the risk of serious injury that could affect their career, never passing up the chance to go back and play with their brothers, sisters, cousins and, in some cases, mothers and fathers. Cody Walker, five-eighth with the South Sydney Rabbitohs, laughs as he talks about the unpredictability of Knockout football. ‘You never know if a centre is going to jam in on you,' or some ‘17-year-old kid step you silly’. Walker plays with his family in a team he helped establish, the Bundjalung Baygal Warriors. Back in 2011 with another group of Warriors, the Mindaribba Warriors, his team won the Knockout.

Other NRL players you are likely to see at a Knockout include Josh ‘The Foxx’ Addo-Carr (Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs); Latrell Mitchell (South Sydney Rabbitohs); Jesse Ramien (Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks); Tyrone Peachey (Wests Tigers); Nicho Hynes (Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks); Andrew Fifita (Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks); William Kennedy (Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks); Albert Kelly (Brisbane Broncos); Dane Gagai (Newcastle Knights); Daine Laurie (Wests Tigers); James Roberts (Wests Tigers); Will Smith (Gold Coast Titans); Brenko Lee (Brisbane Broncos); Edrick Lee (Newcastle Knights) and Connor Watson (Sydney Roosters). They’ll be lining up with — and against — former greats of the game including Greg Inglis, Dean Widders, Dennis Moran, Jonathan Wright, Travis Waddell and many more.

But often the real stars of the Knockout are those players from both the bush and urban areas who didn’t, for whatever reason, make the highs of the NRL. I’m thinking of players I’ve called over past Knockouts such as Aaron Brierley from Yuin Monaro, Mundarra Weldon from Moree, Ryan James from the South Coast Black Cockatoos or the Briggs brothers of the Newcastle All Blacks (NAB). Historically, it’s the players without illustrious first-grade careers who are the ones that people, especially older people in the community, talk about as the Knockout’s all-time best players. Names like Charlie McHughes, Sonboy Peckham, Brett Davis, Michael Lyons and Garry Ardler.

I have seen ‘stacked’ teams (when star players not necessarily from the team’s area are brought in) who get knocked out in round one, beaten by strong community sides that know each other’s games inside out. I’ve watched dominant performances by the Briggs brothers of NAB playing tough, the Rose brothers of Walgett Aboriginal Connection driving their team to success, and the incredible run of the Redfern All Blacks who succeeded thanks to discipline and hard work on and off the field.

The women’s competition has been going for many years, and many believe that the women’s Knockout has been the driver for more professional leagues. It has been largely dominated by the Redfern All Blacks, who won a staggering five Knockouts in a row. Indeed, Redfern is the most successful team overall, winning 11 men’s Knockouts since 1972.

The 2019 Women’s Grand Final, held in Tuggerah on the Central Coast, was won by the Wellington Wedgetails in a tight tussle with Bellbrook Dunghutti Connections. The star of this match was forward Litisha Boney, who plays for the South Sydney Rabbitohs. So many amazingly talented women have gone on to even greater success in the NRLW, as well as in state and national competitions, and as Indigenous All-Stars: Nakia Davis-Welsh (daughter of former Balmain star Paul Davis), Rebecca Young, Simone Smith, Caitlin Moran, Jasmin Allende, Eunice Grimes and current stars of the NRLW, including Shaylee Bent, who plays with the St George Illawarra Dragons, and Caitlan Johnston, who plays for the Newcastle Knights.

Pathway development for younger players has also grown rapidly over the years, with five junior divisions in the Knockout. Just as the 1971 event organisers hoped, scouts turn up to watch the ‘kids’ run around and show their skills. The highlight for those who make it to Monday’s grand final is not only having their game being played live on NITV for the world to see, but getting rare professional vision for a highlight reel they can later show to potential NRL or NRLW teams. Unfortunately, the Knockout has seen sad times. One that stands out for me is the sudden passing of Narwan Eels big prop Alf Atkinson. He was my favourite in the 2008 Knockout held at Kingscliff, on the NSW–Queensland border. With barnstorming runs and brutal defence, Alf led the way up front for the Narwan side, which included Dean Widders and Dennis Moran. But, early on in the first men’s semi-final, Alf came to the sideline and collapsed near his bench. The game stopped while paramedics worked on him. He was taken away in an ambulance, everyone crossing their fingers he would be okay. After consulting with the elders from Narwan, and with Alf ’s family, the team played on, defeating Waterloo and advancing to the grand final. Before that game started, the players were informed that Alf did not survive, a devastating moment for all at Narwan. In one of the most emotional moments I’ve ever witnessed, Alf ’s eight-year-old-son Preston led the team out onto the field, wearing his dad’s jersey. In true warrior spirit, Narwan overcame a 14-point deficit to La Perouse late in the match, claiming the grand final and winning the Knockout. The lasting image for me is of Preston being held aloft on the shoulders of Widders and Moran, cheering their victory.

Not to be outdone by the Kooris of NSW, ‘Murris’ in Queensland also have their own rugby league event, the Queensland Murri Carnival. It began in 2011 and is now named after rugby league immortal Arthur Beetson.

The all-important draw of the men’s competition is one of many highlights leading up to the event each year. The anticipation builds as team names are drawn from a barrel and match ups are announced. Delegates gasp when an arch enemy is drawn, or when nearby communities draw each other. Many times, two teams favoured to go all the way are drawn to play each other in the first round. 2011 Manly premiership winner and Walgett legend George Rose believes that drawing a top seed isn’t always a bad thing. ‘If you get a tough opponent first up and win, it can set up your whole Knockout.’ Walgett have experienced first-round defeats, but Rose is philosophical: ‘We can then rest and enjoy the football like everyone else.’

The Koori Knockout is the most amazing time for our mobs to get together, catch up with people they haven’t seen since the last Knockout, remember family members we have lost in the past year and watch our young men and women, boys and girls, wear their community colours proudly. After waiting three long years to attend a Knockout I cannot wait until the South Coast mob finally get to host the 50th Koori Knockout. I know it will be an amazing event, one that all Kooris can be proud of.

Brad Cooke, a Bidjigal man, is an experienced broadcaster and producer. He will be calling the 2022 Koori Knockout for NITV.

The Koori Knockout exhibition is on show at the State Library, from Saturday 24 September 2022 to Sunday 27 August 2023.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2022.