This story discusses trauma and violence inflicted upon the Indigenous peoples of Tasmania through the process of colonisation. Content within this story may be distressing to some readers.

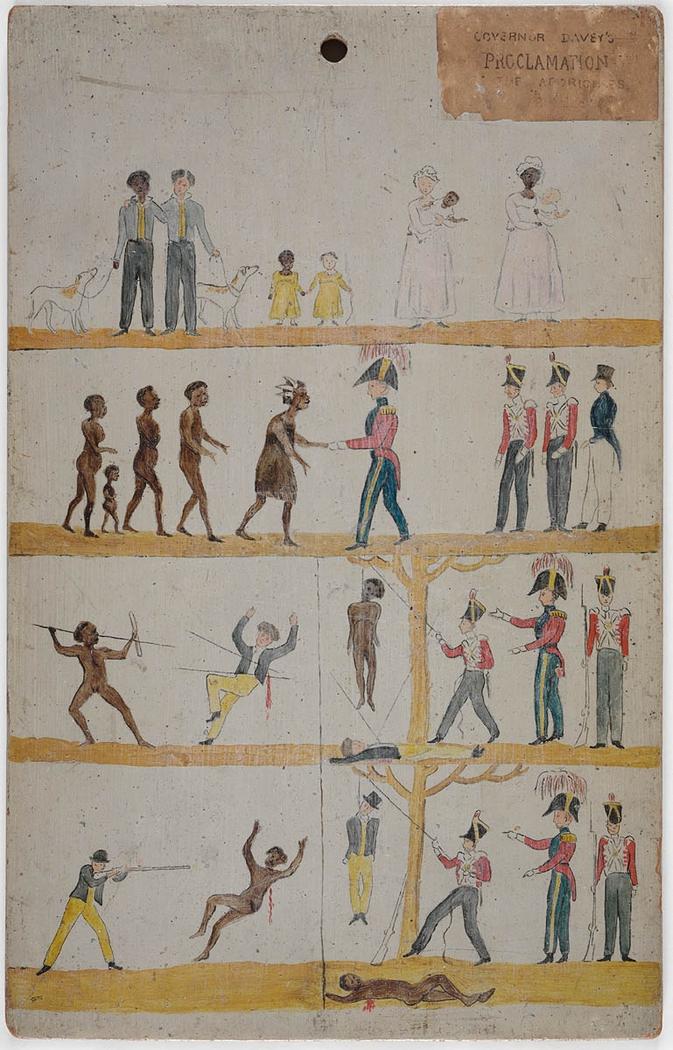

Often incorrectly attributed to Governor Thomas Davey (1758-1823), the Proclamation Board is actually Governor George Arthur’s (1784-1854) Proclamation to the Aborigines. The Board presents a four-strip pictogram that attempts to explain the idea of equality under the law. Those who committed violent crimes, in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), be they Aboriginal Australian or European settler, would be punished in the same way.

George Arthur issued several printed Proclamations during his term as Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land in an effort to reduce the number of violent interactions between the Aboriginal peoples and the British settlers: a period of violence often referred to as The Black War.

As I have explored elsewhere, “the decimation of the First Peoples of Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) was systematic and swift. First Contact was an emotionally, intellectually, physically, and spiritually confronting series of encounters for the Indigenous inhabitants”. There were a few examples of peaceful interactions between the Indigenous peoples and the settlers but the inevitable competition over limited resources, and the “intensity with which colonists pursued their ‘claims’ for food, land, and water, quickly transformed amicable relationships into hostile rivalries”. Conflict was inevitable, with Jennifer Gall observing that, as “European settlement expanded in the late 1820s, violent exchanges between settlers and Aboriginal people were frequent, brutal and unchecked”. The result was the near-annihilation of the original custodians of the land. Indeed, as John Morris has written:

"In 1803, when the first settlers arrived in Van Diemen’s Land, the Aborigines had already inhabited the island for some 25,000 years and the population has been estimated at 4,000. Seventy-three years later, Truganinni, [often cited as] the last Tasmanian of full Aboriginal descent, was dead."

The seriousness of the conflict was reflected in George Arthur’s 1828 Proclamation, published in The Hobart Town Courier, which begins:

Whereas, at and since the primary Settlement of this Colony, various acts of aggression, violence and cruelty have been, from different causes, committed on the Aboriginal Inhabitants on the Island by Subjects of His Majesty.

The Proclamation Board is a very curious, colonial object. The Board did not achieve the purpose for which it was designed and produced.

George Frankland (1800-1838), the Surveyor General, wrote to Governor Arthur in early 1829 and suggested the Proclamation Board (sometimes referred to as a Picture Board or the Tasmanian Hieroglyphics) as a visual tool to support these printed Proclamations. The Proclamation Board borrows from one of the traditional methods of communication for Indigenous peoples: the leaving of drawings on the bark of trees. Governor Arthur’s Proclamation was painted onto Boards and then mounted on trees in remote areas where they would be seen by the Aboriginal peoples. It was also important that settlers saw these Boards as many settlers could not read or write; they, too, would have needed a visual communication tool to understand the Proclamation.

The first image shows Aboriginal people and European settlers living together peacefully. The second image shows leaders, representing the British and the Indigenous, shaking hands. Kate Darian-Smith and Penelope Edmonds point out that this “conciliatory handshake between the British governor and an Aboriginal ‘chief’, is highly reminiscent of images found in North America on treaty medals and anti-slavery tokens”.

The third and fourth images demonstrate the repercussions for committing violence. In the third image an Aboriginal Australian man spears a male white settler and is hanged; the scene is replicated when a white settler shoots an Aboriginal man and is also hanged. Both men are executed under the direction of the Governor.

Approximately 100 Proclamation Boards, oil on Huon pine, were produced. Of these, there are seven known surviving Boards. One of these Boards is held in the collections of the State Library of NSW, having been purchased from J.W. Beattie in May 1919 for £30.

Importantly, the title of the record acknowledges both the popular attribution of the Board and the man who actually instigated the Board’s production: “Governor Davey’s [sic – actually Governor Arthur] Proclamation to the Aborigines, 1816 [sic – actually c. 1828-30].”

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll has described how the Boards were produced by convict artists who had been incarcerated in the island penal colony. A drawing was completed, then a technique of the Italian Renaissance known as pouncing – the pricking of the contours of a drawing with a pin over another surface (in this case Huon pine boards), then dusting the drawing with charcoal, the charcoal dust filling the pin holes to produce an outline – the images, once outlined in this way, were then painted in oil.

The Proclamation Board is a very curious, colonial object. The Board did not achieve the purpose for which it was designed and produced. Yet, this four-strip pictogram was not a complete failure for it serves, today, as a powerful reminder of the processes of colonisation and impacts of these processes upon Indigenous peoples.

References

- Arthur, George. “Proclamation.” The Hobart Town Courier 19 Apr. 1828: 1.

- Carroll, Khadija von Zinnenburg. Art in the Time of Colony: Empires and the Making of the Modern World, 1650-2000. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

- Darian-Smith, Kate and Penelope Edmonds. “Conciliation on Colonial Frontiers.” Conciliation on Colonial Frontiers: Conflict, Performance and Commemoration in Australia and the Pacific Rim. Eds. Kate Darian-Smith and Penelope Edmonds. New York: Routledge, 2015. 1–14.

- Franks, Rachel. “A True Crime Tale: Re-imagining Governor Arthur’s Proclamation to the Aborigines.” M/C: Journal of Media and Culture. 18.6 (2015): online.

- Gall, Jennifer. Library of Dreams: Treasures from the National Library of Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2011.

- Morris, John. “Notes on a Message to the Tasmanian Aborigines in 1829, popularly called ‘Governor Davey’s Proclamation to the Aborigines, 1816’.” Australiana 10.3 (1988): 84–7.