In late 1918, with the Armistice signed, Australians were war weary but also hopeful — the survivors would soon be home with their families and friends.

As peace was taking hold in Europe, however, so too was a virulent form of influenza. This was peace with pestilence.

An estimated one-third of the world’s population was infected during 1918 and 1919. With estimates of the death toll varying from 15 million to 50 million, it seems likely that the pandemic killed more people than the war (in which 18 million perished worldwide). It is even possible that influenza claimed more lives than all the wars of the twentieth century combined.

The 1918–19 influenza pandemic became known as the Spanish flu, but not because it was Spanish in origin. As a neutral country during the First World War, Spain didn’t censor its press, which meant newspapers were free to report that the King and many of his subjects had contracted the disease that was already ravaging much of Western Europe. The word ‘influenza’ originates from fifteenth century Italy, when an upper respiratory tract infection was thought to be ‘influenced’ by the stars.

The history and impact of the influenza pandemic on New South Wales can be seen through collections at the Library: from digitised newspapers on the Trove website to letters, diaries, photographs, ephemera and even dried flowers.

The first infected ship to reach New South Wales was RMS (Royal Mail Steamer) Niagara, which sailed from Canada via New Zealand to arrive at Sydney’s North Head Quarantine Station on 25 October 1918. Its mail cargo was fumigated before it was handed over to the postal service and its passengers were quarantined for seven days. Rather than arriving by sea, the flu entered Sydney via a soldier travelling from Melbourne by train.

On 25 January 1919, Sydney residents opened the Sydney Morning Herald to the alarming headline that a suspected case of the deadly influenza virus was within their city. The infected soldier had been taken to Randwick Military Hospital and the staff who treated him soon became ill.

As the pandemic hit Sydney, the government struggled to contain panic and confusion while it tried to deal with the most serious public health issue it had encountered. On 28 January, to stem the spread of infection, it ordered the closure of all schools, pubs, racecourses, theatres, churches and libraries in the Sydney area, extending the restrictions to Albury two weeks later. In March, the government made the unprecedented decision to cancel the Royal Easter Show. A drawback of these precautionary measures, however, was to increase public hysteria and the spreading of false information.

Relief depots were staffed by out-of-work teachers and over 1200 Red Cross volunteers, who provided blankets, food, masks and medicines to needy families. The Library recently acquired the archive of the state division of the Red Cross covering 1914 to 2014, which includes certificates and photograph albums that belonged to women who volunteered as nurses’ aides during the flu crisis.

At the beginning of 1919, the state had no more than 2000 hospital beds. But between January and September of that year more than 21,000 people were hospitalised. Randwick Racecourse became a 430-bed hospital and the Royal Agricultural Society buildings at Moore Park were used as a hospital and doctors’ and nurses’ quarters. Some of the closed schools and kindergartens were also used as emergency hospitals with wards set up in classrooms. In country areas, temporary hospitals were assembled in the school of arts, showground or any public building available.

Thinking the worst was over, the government allowed schools and churches to reopen on 1 March 1919, but this proved premature. ‘Disinfected by sprayer at school,’ wrote 15-year-old Thomas Herbert in his diary on 7 April. ‘More than half our class away. Influenza getting very bad. A great shortage of doctors and nurses.’ The ‘sprayer’ was most likely a mixture of sulphate and zinc, which was thought to clear the lungs of infection but had no real effect.

Historians believe between 13,000 and 15,000 Australians died of the flu at this time, with two distinct waves in April and July 1919 hitting the hardest. Of the 6244 people who died in New South Wales, nearly 4000 lived in Sydney. The mortality rate among Indigenous people was as high as 50% in some areas. About 30–40% of Australia’s population of about five million was infected. In comparison, during 2017’s flu season in Australia — the worst in a decade — about 1% of the population was infected and an estimated 1127 people died.

After Sydney resident Keith Butler died, his family received 30 condolence letters, five telegrams and 10 cards, some of which were printed on mourning stationery. The collection, donated to the Library by his family in 2016, also includes receipts from the stonemason, the clarinettist who played at his funeral and 15 cards from florists who were asked to prepare bouquets.

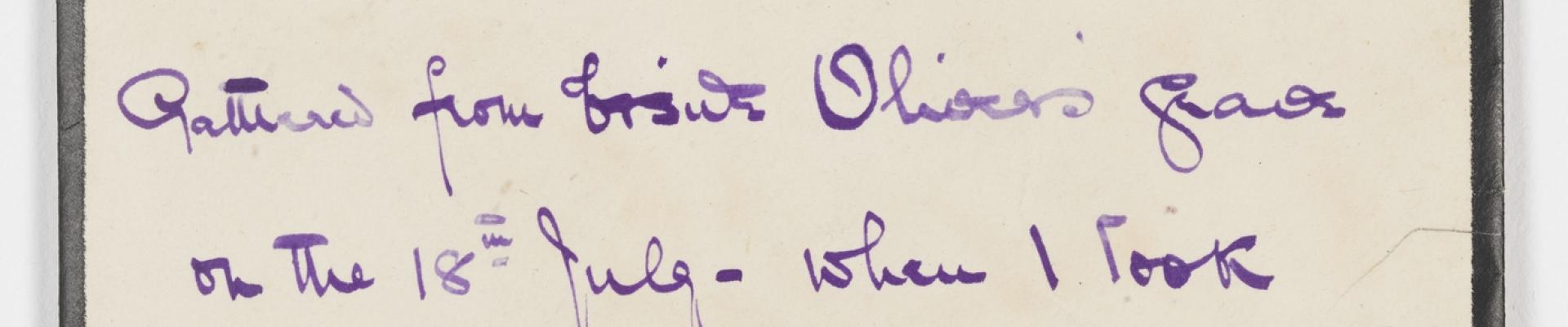

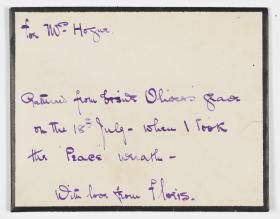

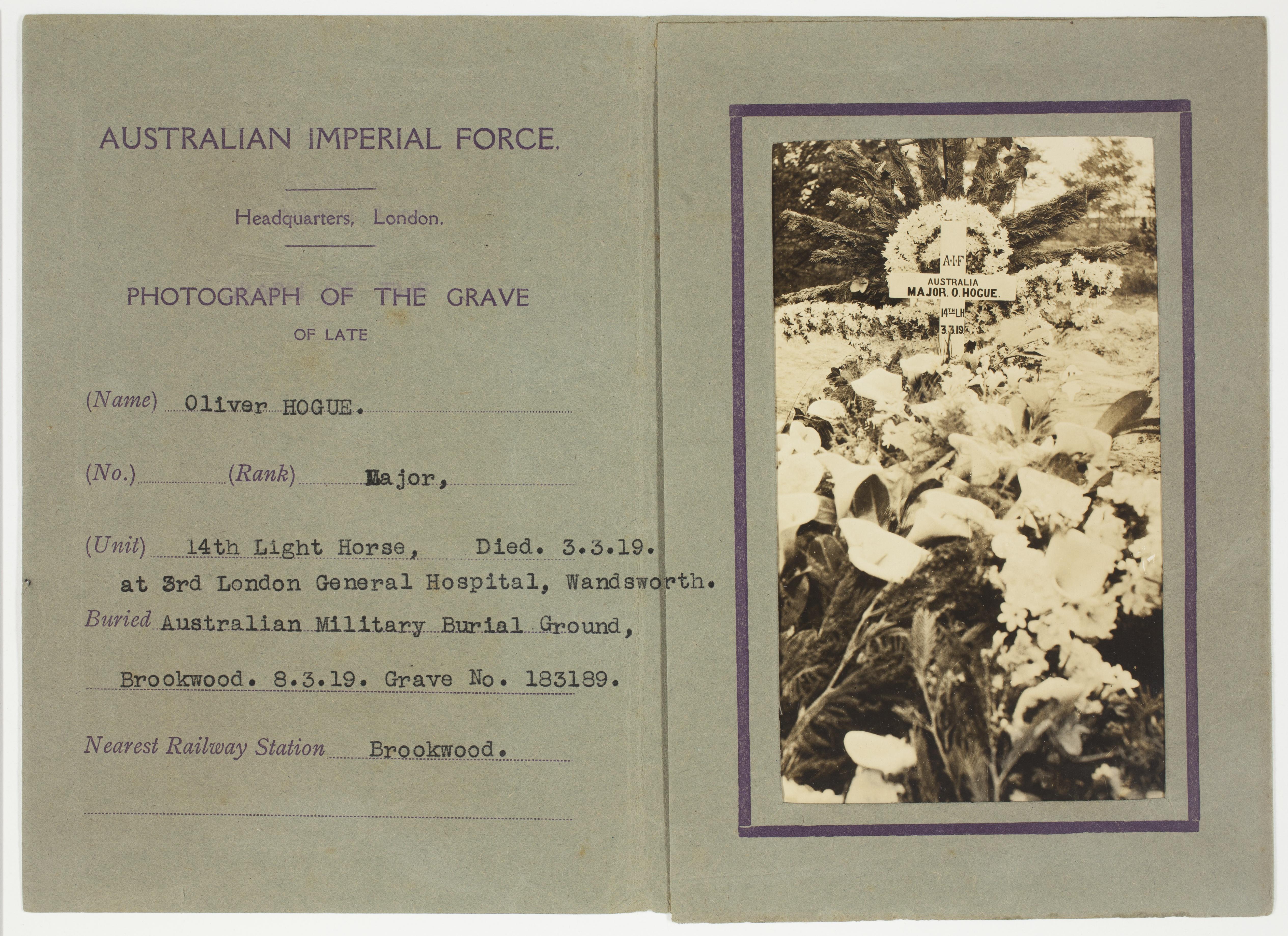

Australian soldier and author Major Oliver Hogue, better known as Trooper Bluegum, survived four years on the battlefields but died of influenza in London on 3 March 1919. The Library holds his books — among them Trooper Bluegum at the Dardanelles and the bestselling Love Letters of an Anzac — which have been digitised and can be read online. In July 1919, a family friend visited Hogue’s grave at Brookwood military cemetery in London and sent back a posy of flowers left by another mourner.

These records recall an event that affected many Australians at the time. If you lived in Sydney in 1919, or in a town on one of the train lines radiating from the city, you were affected by the pandemic. If you were not sick yourself, someone you knew or loved was sick. You were forced to wear a mask, and might have been caring for a sufferer. You were advised to get inoculated and inhale zinc sulphate gases. You may have volunteered with the Red Cross or at one of the relief depots. For a short time, you couldn’t go to school, the pub, church, the races, the theatre or the library and you were afraid to catch public transport and go shopping.

Normal life ceased for six months in the first half of 1919 as everyone from the Prime Minister to schoolchildren tried to manage the outbreak. Australian historian Peter Curson described the Spanish flu as ‘the greatest social and health disaster in Australian history’. But while every town has a monument to those killed in the First World War, memorials to the influenza pandemic are hard to find.

Alison Wishart is a former Senior Curator at the State Library of NSW.