Glance along your bookshelves and you will find other examples of symbols, initials or the publisher’s name.

This practice began in the second half of the fifteenth century, in the early years of the printed book in Europe. The first printers’ marks were found on the last page or on the title page of the book, rather than on the spine. The adoption of a printer’s mark claimed the work as the product of a particular printer or workshop. The first known mark can be found on the Mainz Psalter, produced by Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer in 1457. This mark depicted two shields bearing a saltire, a diagonal cross and a chevron surrounded by three stars. At the outset these were marks of the printer, but the practice was gradually adopted by publishers.

Before the introduction of the printing press in Europe, hand-written manuscripts often included a statement at the end, listing the date of completion and the location. Occasionally the scribe’s name or initials were also included, along with the person who had commissioned the work. The term for this final text is a colophon, from the Greek word κολοφών, meaning summit, or finishing touch. This convention was carried across to the design of the printed book. The printer’s mark was added to the colophon but gradually moved to the title page. By the end of the fifteenth century, thousands of books were being printed across Europe and England. It was not unusual for rival printers to produce pirated copies of popular works. The use of a printer’s mark strengthened printers’ claims to be the source of the original edition. Licences or regulations by printers’ guilds sometimes protected printers’ rights, but these were limited to smaller jurisdictions, cities or single countries. Copyright legislation would not be introduced until the eighteenth century.

Following the same trajectory as book illustrations, the earliest marks were simple designs produced by using a woodcut stamp. Later, more intricate woodcuts and engravings were incorporated into the design of the book’s title page during production.

The design of a printer’s mark used visual puns, wordplay or sometimes a rebus, a puzzle combining illustrations and letters to depict a motto or printer’s initials. Sacred symbols, the cross and the orb, real and mythical animals, heraldic symbols, and scientific instruments were used in thousands of combinations. The sixteenth century was the highpoint for printers’ marks, when lavish illustrations incorporating a printer’s mark decorated title pages.

Many famous images and symbols originate from printers’ marks. The design used by Venetian printer Aldus Manutius depicts a dolphin wrapped around an anchor. The printer’s mark used by French printer Robert Estienne shows a man standing by an olive tree, symbolising the tree of knowledge. Christophe Plantin, in Antwerp, used a pair of compasses held by a hand extending from a bank of clouds, the compass points signifying labour and constancy.

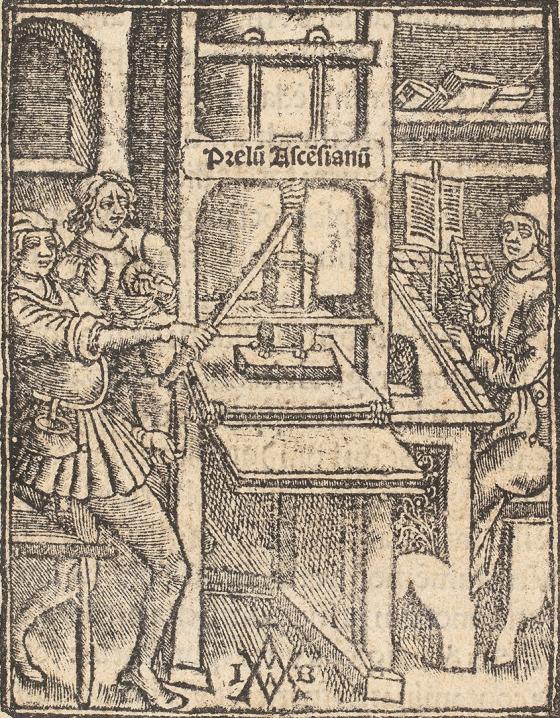

The first mark to incorporate an illustration of a printer at work was Jodocus Badius, based in Paris between 1503 and 1535.

Use of these marks has declined over the centuries but has never disappeared. In the late nineteenth century, the rise of the Private Press movement led to many modern printers’ marks, including the devices used by the Kelmscott Press, Ashendene Press and Golden Cockerel Press.

Today, printers’ marks appear in works by fine and private press publications produced by specialist printers.

Several of the Mitchell Library’s external decorative features pay tribute to the work of early printers. As you walk between the two buildings of the State Library towards the Domain, opposite the Library’s coffee shop, look up to your left. On the southern façade of the Mitchell building, you will see carved in stone the mark of William Caxton, the first English printer.

Maggie Patton, Manager, Research & Discovery

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2022.