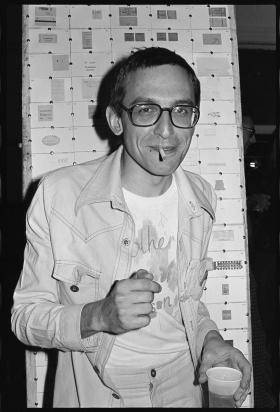

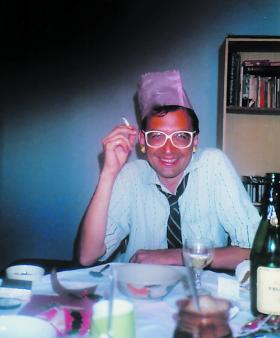

Here are reflections from Sasha Soldatow’s biographer on her complicated subject and his unwieldy, impossible-to-contain life.

He was a vivid presence, a bold writer, an original thinker, multi-talented, an anarchist, an activist, a dedicated partygoer and freelance provocateur. His story is also about the many social movements he was involved with: gay liberation, anti-censorship, prison reform, action to save inner-city housing, alternative publishing, cabaret. The biography, I decided, would be subtitled ‘The life and times of Sasha Soldatow.’

I began researching uncertainly but felt increasingly that this was a project worth doing.

Interviews I did with people who had known him were essential, and reinforced that Sasha was remembered where most other people had become a blur of the forgotten, that he was influential in many lives. Besides these interviews, the most important source for my research was the papers Sasha had deposited in the State Library of NSW.

I knew Sasha wanted — even expected — his biography to be written. (I don’t think he eve thought I’d be the one to do it.) This knowledge countered the icky feeling of delving into someone’s personal letters and notes. There I’d find his frequent assertion that his historical sense insisted on intimate tellings. Sasha had placed his archived papers in the Mitchell Library with no restriction on access; they were meant to be read. There were even folders titled ‘for biography’: handy labels for his future biographer(s). There are at least 40 boxes of notebooks, drafts, newspaper cuttings, photographs and, mostly, his letters.

Fascinated, I’d started working on the biography before I realised that I was committed to it. It began as someone else’s idea; others said, ‘Good idea, do it’ and I eventually wondered, ‘What if …’.

As David Marr said in his interview with me, ‘That collection speaks from grave … He was waiting for you, Inez.’

I knew Sasha wrote letters — we exchanged a few once — but I didn’t know the extent of it. His boxe reveal that from the early 1970s he kept every letter he received and carbon copies of the ones he wrote. He kept letters marked ‘not sent’. When, later, there was some correspondence via fax, he made a print copy — smart, because faxes fade fast. In the last few years of his life, he printed out emails.

While new forms of communication inspire their own fresh brilliance, there’s a sense of loss seeing archives like this; it was such a common practice — long letters on paper between friends, sent in a stamped envelope. I did groan, however, when I uncovered handwritten ones — before typing was so ubiquitous, was handwriting easier to read?

Sasha’s letters are uninhibited yet highly literate — correct grammar, precise vocabulary and punctuation, even in his later years when he was succumbing to the effects of a dramatic accident in Russia that, to some extent, disabled him and worsened his addiction to alcohol and pills.

From his earliest days to his latest, he would say that friendships and relationships were his real life’s work. The evidence of this work is in his letters.

He fell out with some people and told them how they had failed him.

He wrote obsessive agonies over another fall into romantic love.

He entertained, complained, praised, scolded, pontificated.

Some of Soldatow’s best work is in his letters. He knew it: they were at times a first draft for pieces in Private Do Not Open [PDNO] (1978) and Mayakovsky in Bondi (1993), his books of short prose that disturb notions of genre, mixing essay, poetry and fiction writing.

While these books were critically praised on publication, they did not remain in print. Possibly their unique idiosyncrasy accounted for the marginal status that embittered him and was an inevitable topic in many of his letters over many years.

I knew that Bruce Sims (1948–2023), who worked at Penguin for many years and later at Magabala Books in Broome, was always valued by Sasha as an editor and friend. The boxes reveal their shared past in university theatre, the wealth of editing work and advice Sims provided on PDNO, and their close connection until the end of Sasha’s life. Forty years later, Sims gifted his labour as the perfect editor of Sasha’s biography.

I knew Sasha had moved to Sydney in 1972, attracted by its anarchist traditions, because he said so, as his archives remind me: he said it often in interviews and written pieces, all, of course, carefully filed. At university in Melbourne, Sasha already had been reading the University of NSW student newspaper Tharunka, edited by a team who were driven by the political zeal of the day, as Sasha was: anti-war, anti-sexism, anti-censorship, anti-authority.

Back then, student newspapers were widely read. Tharunka exposed and provoked the establishment by publishing investigative reporting and censored material — Australian censorship was ludicrously repressive in those days.

Sasha was keen to be part of all this. Before the move he'd met one of Tharunka’s editors, Wendy Bacon, who would become a friend and colleague. Together, soon after, along with others, they began the alternative–underground newsletter Scrounge. Copies are filed in his archive: its grunge aesthetic speaks of the limited printing options of the time. The content is a collage of eclectic, if limited, sources: other underground publications and Scrounge’s own investigations.

In a different vein, Sasha went on to produce the absurdist, irreverent newsletter The Only Sensible News with a group of friends, including me — his diary and notes are a reminder of the juvenile hilarity of its creation. Sasha named our creative collective ‘Drink Against Drunkenness’, now my biography’s title.

More sophisticated in quality were Sasha’s Patterns series of poetry and polemic. Like a lot of people around at the time, I remembered only fragments of all of this. Drafts and copies are a testament to the meticulous attention to every line. These are pamphlets meant to be kept. They are also evidence of advances in printing technology and the essential role of Tomato Press, the new press for alternative and underground publishing, including poetry, posters, t-shirts and magazines.

Starting research for the biography, I soon learned that Sasha’s 1983 essay ‘What Is The Gay Community Shit?’ (WITGCS?), in the style of his Patterns pamphlets, was the most remembered piece by him. Sasha was a well-known identity in early gay liberation. He wrote for the gay press as soon as it came into being.

The ideas forcefully articulated in WITGCS? were, basically, that being gay did not in itself mean like-mindedness with all other gays. Also, that capitalism subsumes everything, including liberation movements. Sasha’s later opinion pieces returned to this essay and even after his death it was quoted and read, a testament to the continued relevance of his arguments in the era of the ‘pink dollar’ and popular queer eyes.

His archives disclose not only the careful drafts of WITGCS? but that earlier collaborative paper written with Larry Strange — a lawyer who had a tempestuous relationship with Sasha at that time — was where these political perceptions were first presented, at an anarchist conference in 1978.

Anyone who remembers Sydney in the 1970s would understand a voluntary migration from Melbourne. But there was more than anarchist activism and gay society to move towards; there was what Sasha would leave behind.

His old self. His mother.

Friends knew of Sasha’s stormy relationship with his mother. His humorous and bitter grievances are repeated in his letters over the years. But it also becomes evident that he cares for her; his letters to her are more formal, there’s a different tone to them.

Most revealing of all, among old passports and photographs, is the document Sasha worked on near the end of his life on his mother’s behalf: a submission to the German Forced Labour Compensation Programme of the International Organization for Migration. His compassionate, painstakingly well-written account details her harrowing experiences in World War II, as a young Russian woman working in a forced labour camp. Sasha’s lifelong if incomplete knowledge of this always complicated his complaints about her.

Sasha is remembered as a central character in the famous squatting action in Victoria Street, Kings Cross, during 1973 and 1974, when he joined residents and supporters in a bid to save the street from greedy developers who would destroy its architectural and social heritage. His archives disclose a rare copy of an extensive piece he wrote at the time describing life in the squats. Part of his forensic examination of the politics of the protest groups (sexism, conflicts over desires for official positions and standard hierarchies) was the essential and historically significant alliance with the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) whose green bans saved some of Sydney’s built and natural environment.

The hyper-masculine style of the labourers was tinged with casual homophobia, but Sasha got on well with them, offering respect and humour from his frank, unapologetic gay self, and was respected in turn. Soon after this action, the BLF put a green ban on Macquarie University for its dismissal of an academic for being gay.

I knew how much Sasha took meticulous care over every word and sentence and this made him a valued editor to many writers (I’d been one) of prose and screenplays, many of whom went on to be published or produced. In his letters he often wrote, ‘I crave details.’ He was a sought-after mentor to new writers, perhaps most famously Christos Tsiolkas: Here, in the 40 boxes, are the letters and drafts as the novel that would become Loaded took its shape and was published under Sasha’s guidance. The two writers became closer and co-wrote the provocative Jump Cuts: An Autobiography (1996).

Here are copies of the testimonies many writers wrote on Sasha’s behalf when he embarked on legal action against the Australia Council for the Arts for failing to award him a grant for 16 years. This case was, for a long time, what most people knew about Sasha: here are folders full of the newspaper reports and opinion pieces; it seemed everyone in the literary world discussed the case.

And here are lengthy files of his meticulous legal research and correspondence with his lawyer: in some contexts, Sasha showed great organisational ability, focus and discipline.

I had listened with a group of friends to Sasha’s 1988 radio program on Harry Hooton. I find in his boxes just how serious and prolonged his interest was in the visionary anarchist poet, an intellectual forebear. Two years later, Sasha published a thoroughly researched introduction in his admired edition of Hooton’s works, and in the early 2000s he enrolled to do a PhD on Hooton. Sadly, his health worsening, he was unable to continue.

I knew Sasha was involved with ‘prison stuff’ as an activist: here is his material on prisoners’ rights and prison reform. He even did a stint as writer-in- residence at Long Bay Jail and corresponded with notorious prisoners such as Ray Denning. Sasha shared a house with some formative members of groups like Women Behind Bars and Prisoners’ Action Group and would cite their work as shaping his thinking. He acknowledges them in his 1980 non-fiction book The Politics of the Olympics; rereading it for the biography (in the Library — it’s hard to find a copy) was to remember that it is thoroughly researched and brilliantly written and begins with a poetic dedication to all prisoners.

I knew that Sasha called himself ‘Party Fun’; he would go to all the parties he could and threw quite a few himself, as he recounts in many letters and journal entries. He also created a theatrical persona for electrifying performances of his own work in cabarets, readings and his own shows: here are drafts of lines and stanzas rewritten over and over.

Less known is just how depressed he could be, the angry and despairing moods that recurred throughout his life expressed with dark bitterness.

There is little chronology in his files — letters are filed by people’s names — but once you’ve read most of them, it’s clear that despising and avoiding psychiatry was his lifelong position. He also avoided, even mocked, any form of therapy or technique of self-examination.

I knew he had died at the age of 58, of liver failure. His archives illuminate the story of his lifelong addictions. Almost literally lifelong: he had been prescribed Valium as a teenager and kept taking the drug, referring to it often as some kind of essential component of his life. Sasha drank regularly from an early age; in Sydney his social group drank, and no one became worried about the extent of his intake until it was too late.

‘You can’t sit still in a corner and just look when the world around you demands an answer, or a commitment.

You cannot be a poet without politics.

We believed in something.

Don’t ask me what it was.’

Inez Baranay is the author of Drink Against Drunkenness: The Life and Times of Sasha Soldatow (Local Time Publishing). She is the author of nine novels as well as books of short prose and memoir. Having lived and worked around the world, particularly in Bali, India, Morocco and Turkey, she is based in Sydney, at least for now.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2023.