She wrote him a letter and left it in his schoolbag the day before, informing him that she wanted to meet at the Parks Community Centre Library. He decided to look through some books as he waited, and he was so immersed in what he read that the hours went by quickly. Imagine the confusion and anguish he might have felt under different circumstances — if he had not been surrounded by hospitable and consoling worlds.

He was in love with a ninth-grade classmate two or three years later. He couldn’t meet her eyes, or speak to her directly, even though he’d done both of those things without any trouble just a few weeks before. He’d dreamed about her one night and woke up a different person — the kind who couldn’t look her in the eye. The boy saw that she spent her time browsing books from the poetry shelf during a weekly visit to the school library, so he searched the same shelf and selected several volumes for himself when the class was over.

He picked up those books because they promised to show him something he was too shy to explore directly. He hoped to gain insights into the girl’s inner world. Poetry offered him the words and phrases that she had read, images and feelings that passed through her and now to him. That is what made it compelling at first. But as the boy continued to read, he came to feel that he was discovering unknown parts of himself in the process, that the poetry understood him but was also shaping him.

The boy’s devotion to books and to love was brittle. He allowed a different girl to covertly stroke his thigh in the same school library just a few weeks later. He pretended to stare thoughtfully at a volume of poetry in his hands while the girl he adored focussed on her work at another table. He did not have romantic feelings for the thigh-stroking girl, but her impulses surprised and thrilled him: the secret intimacy, her cool hands, a sense that they shared a sudden, powerful yearning that was wholly of the moment and would have no sequel. This was better than poetry, he knew — far better — but was it better than love?

His feeling for the girl who read poetry gradually faded. He looked her in the face and talked to her without nerves because she’d lost half of her meaning. The boy had fixed his eyes on poetry instead. He imagined that he was in the process of becoming an author of books that unknown girls or women would one day take from the shelves of unknown libraries. The knowledge that they were reading his books would resemble the feeling of being secretly stroked on the thigh by a mysterious companion while he pretended to read a volume of poetry.

In his middle teens he visited the West Lakes Public Library after a brief self-inflicted illness and borrowed two large Russian novels. He went back a week later and borrowed more Russian novels. In the years after, the boy spent hours searching the shelves of the Port Adelaide Public Library and the Semaphore Public Library, in a manner that must have seemed compulsive to anyone who bothered to notice. He’d scan each shelf very carefully, then search the same shelves again from a different direction, moving back and forth, picking up a book and reading a sentence or paragraph, then putting it back or clutching it to his chest. He was looking for something and was confident that he would find it because the library always provided what the boy needed, though he could never guess what that would be before he discovered it.

The boy knew that he was lucky. Other people his age needed money because their ideas of experience, discovery and intimacy involved travel and costly social events. If they had no money, they were deprived of those things. The boy had no money, but he knew that he was not wholly impoverished because he could discover parts of himself and experience foreign worlds and feel an intimate connection to the characters and narrators who lived in the books housed in the library. The boy did not feel that this was pathetic. Instead, he believed that he had access to an astonishing wealth that others did not appear to perceive, and because they couldn’t see it they were forced to strive for other forms of enrichment.

Perhaps the boy was occasionally homeless. Perhaps he ran out of food a few times. Perhaps he had no good reason to hope for a better future. Perhaps he was so alone that he was nearly sick with loneliness, and so untethered from normal feeling that he sometimes felt capable of almost anything. But when I think back to those years, which were difficult in almost every way, I think of all the promises fulfilled more than the deprivations endured. I remember searching for something I couldn’t name and finding it again and again, in the Port Adelaide Public Library.

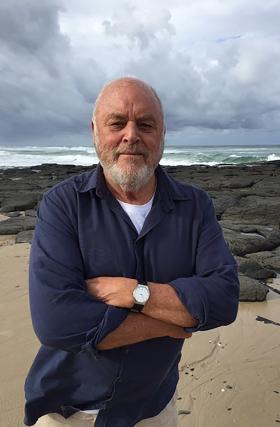

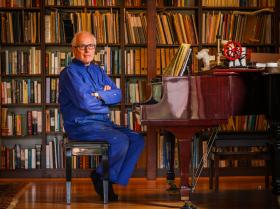

Shannon Burns is the author of Childhood: A memoir, published by Text.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2023.