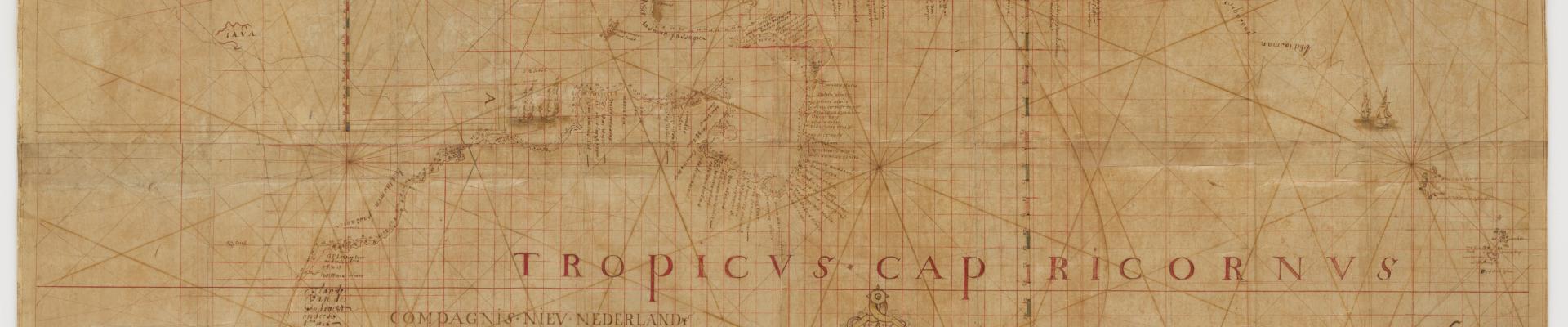

One of the Library’s most valued possessions, the Tasman Map, displays the results of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman’s two voyages to the southern ocean between 1642 and 1644.

Hand-drawn and decorated on Japanese ‘gampi’ paper, the original Tasman map is one of the most irreplaceable objects in the State Library’s collection. It is the only record of Abel Tasman’s two voyages between 1642 and 1644.

The map’s detailed wind compasses, sea monsters and decorative features indicate that it was created for display or publication rather than for practical navigational purposes.

It was presented to the Library in 1931 by Princess Marie Bonaparte, but the origins of the map are unknown.

It may have been drawn in the late 1640s under the supervision of Tasman’s chief pilot, Franz Jacobszoon Visscher, and Isaac Gilsemans, a merchant on both Tasman voyages. The map may also be a late 16th century copy of the original map created during the voyage, now lost.

It is presumed that the map lay hidden in an archive in the Netherlands until the mid-19th century, when Dutch mapmaker Hulst van Keulen offered it to the Dutch map-seller Frederick Muller. It was later acquired by Prince Roland Bonaparte, the great-nephew of Napoleon, who intended to give the map to Australia after he died.

What was Tasman doing in the Southern ocean?

Tasman made two voyages on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, seeking out new opportunities for trade to the south and searching for an alternate route across the Pacific Ocean. He was commissioned by Anthonie Van Diemen, Governor-General of the Company in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), which was the centre of the lucrative spice trade in the 17th century.

During his first voyage in 1642–43, Tasman sailed from Batavia to Mauritius, then southward to the Australian continent where he charted the coast of Tasmania (which he called Van Diemen’s Land), the west coast of New Zealand, and parts of Tonga and Fiji. He also charted the north coast of New Guinea before returning to Batavia.

On his second voyage in 1644, he explored much of Australia’s northern coastline and the south-west coast of New Guinea as he sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Although Tasman’s voyages left many questions unanswered — he did not realise that Tasmania was an island, nor did he plot the eastern Australian coastline to determine whether it joined New Guinea — he achieved a great deal. Until the Pacific voyages of Captain James Cook from 1770, Tasman’s explorations represented the extent of European knowledge of the Australian continent.

The Tasman Map has been recently scanned through the Google Cultural Institute Art Camera Project. You can view the incredible detail through the Cultural Institute Site.

Where does Daisy Bates fit in with the story of the Tasman map?

How the State Library acquired the Tasman Map starts on the Nullarbor Plain in 1926. Anthropologist and welfare worker, Daisy Bates, described later by the Principal Librarian of the time as ‘the most isolated white woman in the world’, had been reading Round the World, a 1904 travel memoir by geographer James Park Thomson. In the book, he mentions visiting the President of the Geographical Society of France, Prince Roland Bonaparte, in his mansion in Paris. Here Thomson sighted Abel Tasman’s map of Australia displayed prominently and protected behind a curtain. The Prince explained to Thomson that after his death, the map would be given to the Australian people. Apparently Prince Roland would have liked to have come to Australia himself however he was terrified of snakes. Thomson unsuccessfully tried to reassure him that it was highly unlikely he’d ever see a snake if he made the trip.

‘the most isolated white woman in the world'

By the time Daisy Bates read Thomson’s memoir, Prince Roland Bonaparte had been dead for two years, and there was no sign in Australia of the map.

From her bush camp in South Australia, Bates wrote to the Chief Librarian, William Herbert Ifould, and urged him to investigate the location of the map. Ifould found out that the map was with Bonaparte’s only child, Princess Marie Bonaparte, wife of Prince George of Greece.

Princess Marie knew of her father’s intentions but her husband wanted to come out to Australia and present the map himself. This was not going to happen for a few years, and Ifould was concerned that, by the time the planned trip occured, Prince George may hand it to the Commonwealth authorities by mistake. In 1929, Ifould asked Lord Chelmsford to warn him of any imminent visit. By 1932, the prince’s visit was still some years away, and the Princess agreed to give the Library the map. The Tasman Map eventually arrived in Sydney in 1933.