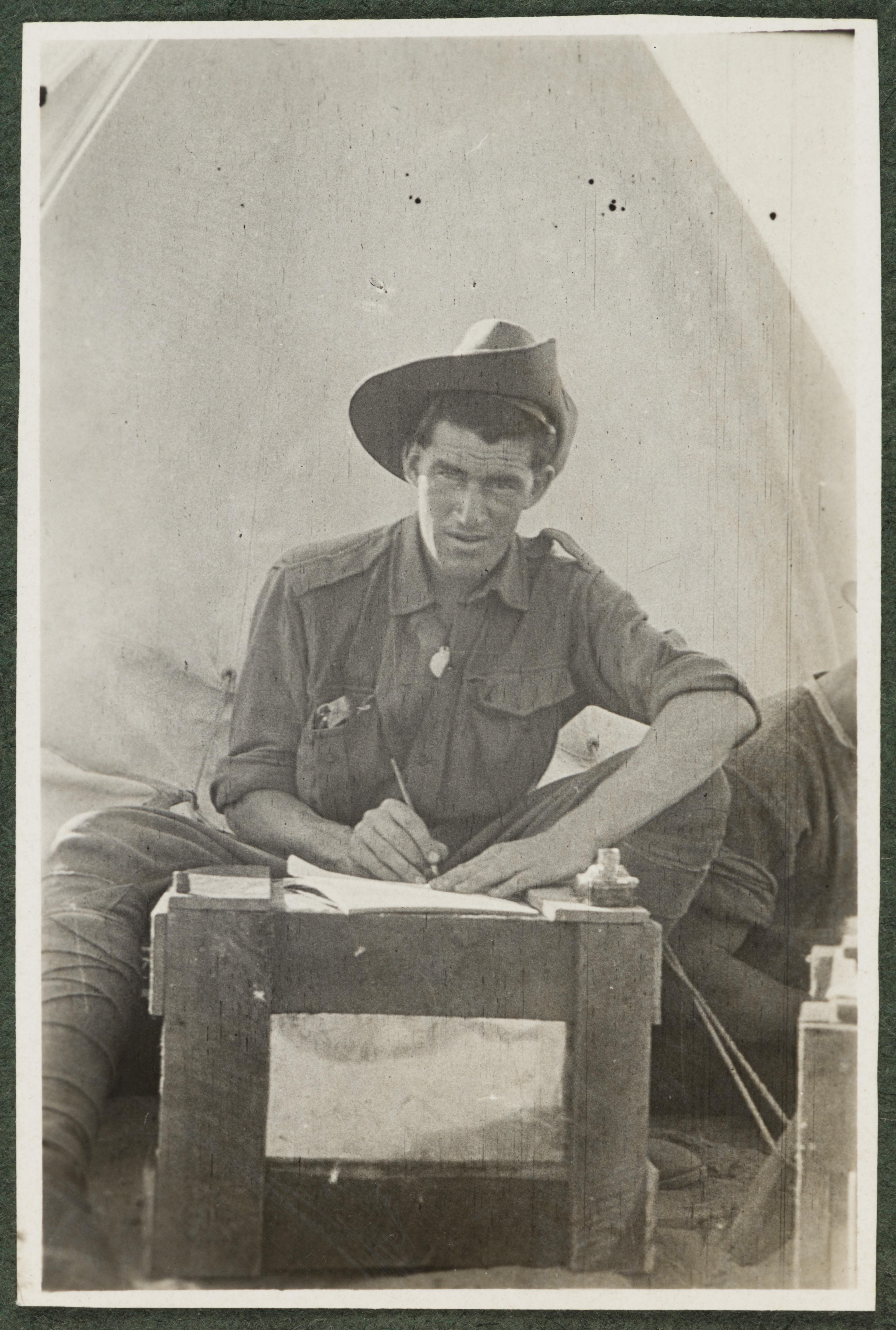

Most of the 330, 000 soldiers who went abroad preferred to write letters or postcards if they wrote at all. But thousands kept a diary, not of the introspective or confessional kind, but rather a spectator diary, a record of travel and war, of tourism and duty done, something to be sent home, or to carry home; to be read by family and friends or, perhaps, to be consulted later, to confirm a memory or fuel a reminiscence.

Australians are privileged to have a wonderful collection of these diaries at the State Library of New South Wales in Sydney. The collecting began before the war ended. As events at Gallipoli seized the nation’s imagination, the Principal Librarian, William Ifould, was formulating an acquisition policy in haste. Ifould was determined to collect first-hand accounts of battle written by the front-line men. With the approval of his Trustees, he placed advertisements in newspapers around Australia and in Britain, offering to buy diaries and letters in original form. The Library’s Letter Books for 1918–22 reveal that some diaries subsequently offered to Ifould were rejected on grounds of being insubstantial or in some way rewritten or overwritten later. Authenticity was at a premium.

By 1919 the collection was already a valuable one. By the mid 1920's the total number of war diaries in the Library had reached 236, complemented by collections of letters and in some cases photo albums, artworks and maps. Today the collection stands at around 550 diarists and over 1, 100 volumes.

These diaries take many forms. Some were written on odd sheets of paper or in memo books or signal message books. Others were cloth or leather bound. Occasionally the narrative begins in a hefty gilt-edged volume but inevitably continues in any kind of notebook that comes to hand. Most diaries were pocket-sized and fit for purpose.

The variety of bindings complements the range of writing styles. Some are terse and random: ‘Getting warmer. Glassy sea with strong under currents. Dance for nurses and officers. Commenced growing a moustache.’ Some are prolix and strain for literary effect: ‘The sun as it arose threw a golden glory over the distant horizon and finally appeared in a great white disc in all its glittering heat.’ Some don’t strain at all and achieve a lyricism that seems effortless.

A small number of diaries were acquired from the families of men killed abroad but the majority in this collection were purchased from men who made it home, survivors, many of them diarists over two, three or four years. Their chronicles bear the hallmarks of the true diary. They are not carefully planned, they are raw and unpolished and rich with the ‘diamonds’ of more or less spontaneous jotting. Their pre-eminent quality is an unpretentious authenticity and immediacy, a realism that is rarely matched by other records of wartime experience. They are intensely ‘in the moment’, all the more so in the trenches where death was everywhere.

Why did they write them? Firstly, they did so because they could. Australia was an unusually literate society for the time and many were schooled enough to tell their story. And what a story! The soldier-diarists, and the airmen, sailors and nurses who kept a diary, knew they had a big story to tell. They often used the word ‘adventure’. One even gave his diary a title. He called it ‘the great adventure’. But the innocence or the optimism suggested by this phrase was short-lived. The ‘great adventure’ was mugged by war and soon enough we see a change – the language becoming darker as the romance disintegrates.

For some their cryptic notes were probably no more than an aide-memoir. For others, the diary was a way to connect with home. They were writing for an imagined audience, for the family and friends they had left behind. The importance of a ‘conversation’ with home can hardly be overstated. Along with letters and postcards and sometimes photographs, the diaries were the Facebook of their day — impressions and experiences for the kitchen table or the mantelpiece.

Last but not least, these wartime chroniclers wanted a record of duty done. They wrote of hard training and hard times, of battle and death and ruin everywhere. There are lines, hastily scrawled upon the eve of battle, by soldiers who knew this entry might be their last. There are passages where men puzzle as to how they could still be alive.

These are voices full of life and fun and fear, and resolute purpose. They are voices from the greatest tragedy of the twentieth century, a tragedy that engulfed an age.

The diaries vary in style and language; from the harrowing, to the mundane, with many instances of the wry sense of humour of the servicemen and women, the stretcher-bearers, POW’s, artists, journalists and entertainers, amongst many others.

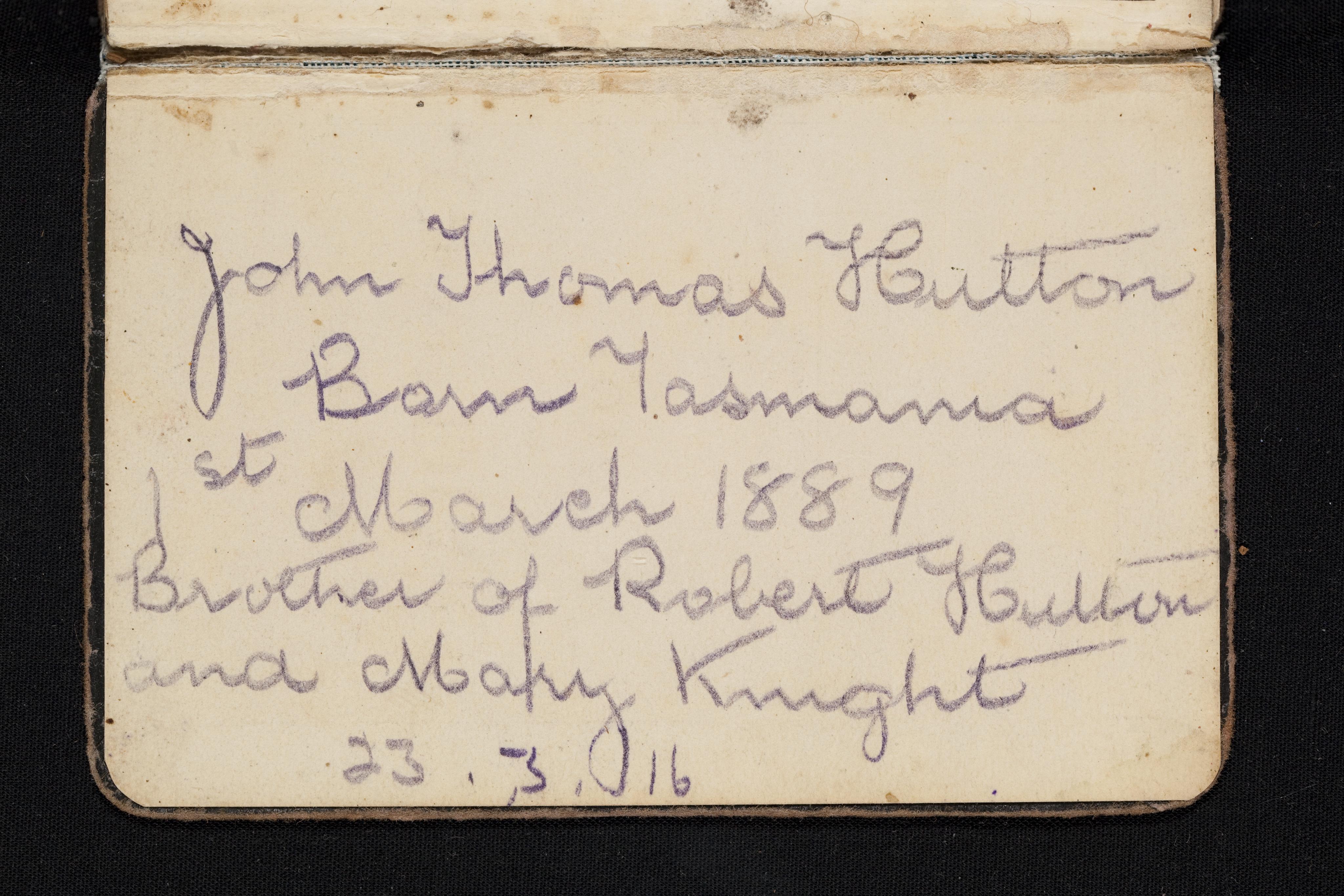

Jack Thomas Hutton

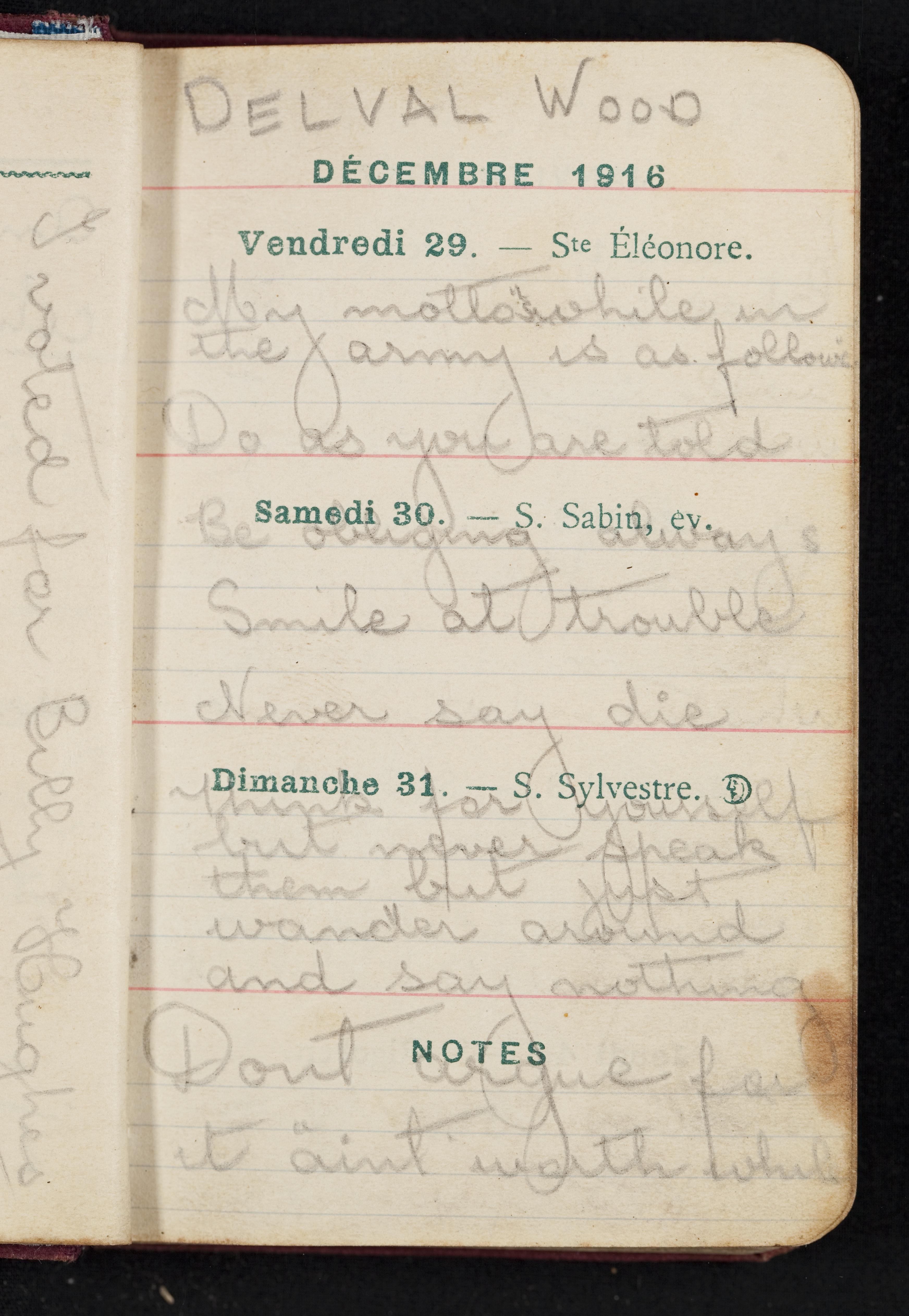

Jack Hutton inscribed his motto at the beginning of the second volume of his diary:

My motto while in the army is as follows

Do as you are told

Be obliging always

Smile at trouble

Never say die

Think for yourself but never speak them but just

wander around and say nothing

Don’t argue for it ain’t worth while

Jack was a 26-year-old farmer from Carnsdale in New South Wales. He enlisted in October 1915 and had been serving in France for around a year when he wrote his motto. He had survived the horror of Pozières to describe it as ‘murder bloody murder’.

More like poetry than a conventional diary, Jack’s account uses dark humour to recount tales of soldiering in one or two short sentences each day. He likes a drink and the company of French women, but goes to church on Sunday. He takes good care of the horses, but his Padre calls him the ‘Little Disgrace’. With so many girls back home in Australia, letter writing takes a whole evening.

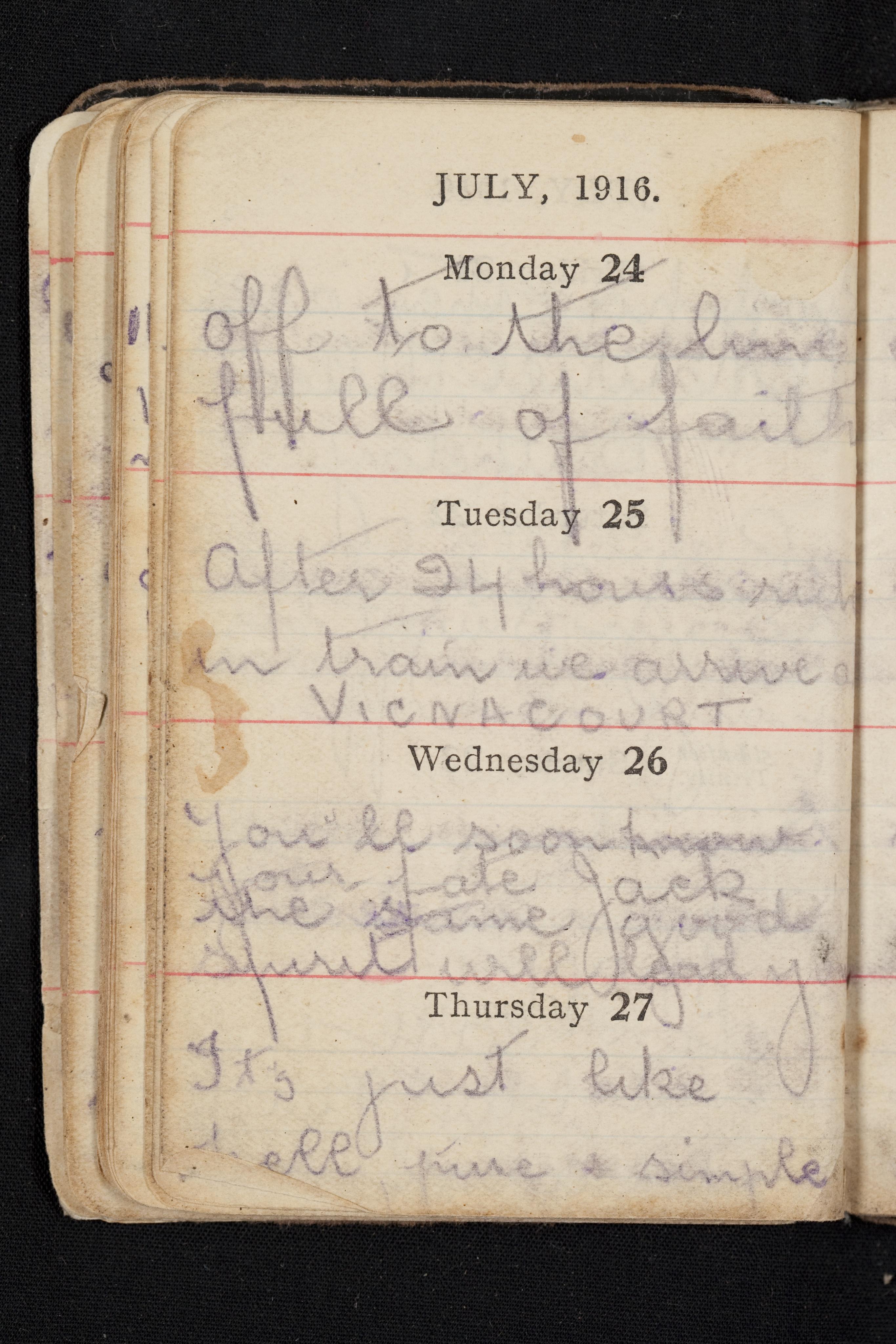

Jack's diary moves quickly from the terror of the front to his enjoyment of the French towns behind the frontline:

Monday 24 [July 1916]

Off to the line full of faithTuesday 25

After 24 hours ride in train we arrive at VICNACOURT [sic]Wednesday 26

You’ll soon know your fate Jack

the same good spirit will lead youThursday 27

It’s just like hell pure & simple

….

[July–August, 1916]Monday 31

Wipe the scenes away they are awfulTuesday August 1

Thundering guns and flame lit skysWednesday 2

Men brave men of Australia

a heroic breedThursday 3

How long O Lord

how longThursday 17 [May 1917]

Last night was spent in Writing home,

too too many girlsSENLIS- Friday 18

“Senlis” our first stop moving tomorrow

we all got full on ChampagneSaturday 19

Arrived at Reubempre seems a nice placeSunday 20

The country side is a perfect picture

Staying with a dear old lady …CONTAY

… It is just fine rambling among these villagesSunday 27

Believe me the French women are OK

I still go to church

Jack stayed in England after the Armistice was signed, working as a clerk in the Finance Department. Before he returned to Australia on 25 September 1919, he wrote to William Ifould, the Principal Librarian at the Mitchell Library in response to an advertisement in the London Daily Mail offering ‘good prices’ for war diaries judged to be ‘good material’:

Sir,

In reference to your advertisement, “London Daily Mail” re the “Diarys” [sic] of Australian soldiers, I beg to report that I have a dinkum little journal, brief but to the point of three years warfare dealing with almost every scrap that the Aussies fought in France from Pozieres until the armistice and I doubt if any Diggers who knocked about the forward area have such a complete and authentic record of what we did in the great war as I have and the record of my unit (17th Battalion) stands second to none, so you can depend on it being ‘good material’ and worthy of a good price …I am sir, in all sincerity,

Jackie Hutton

The Library purchased Jack Hutton’s diaries for £7.

Sister Anne Donnell

Sister Anne Donnell also offered her diaries and letters for sale in 1919. Despite Library staff concern that she didn’t concentrate enough on medical or war matters, she was offered £5.

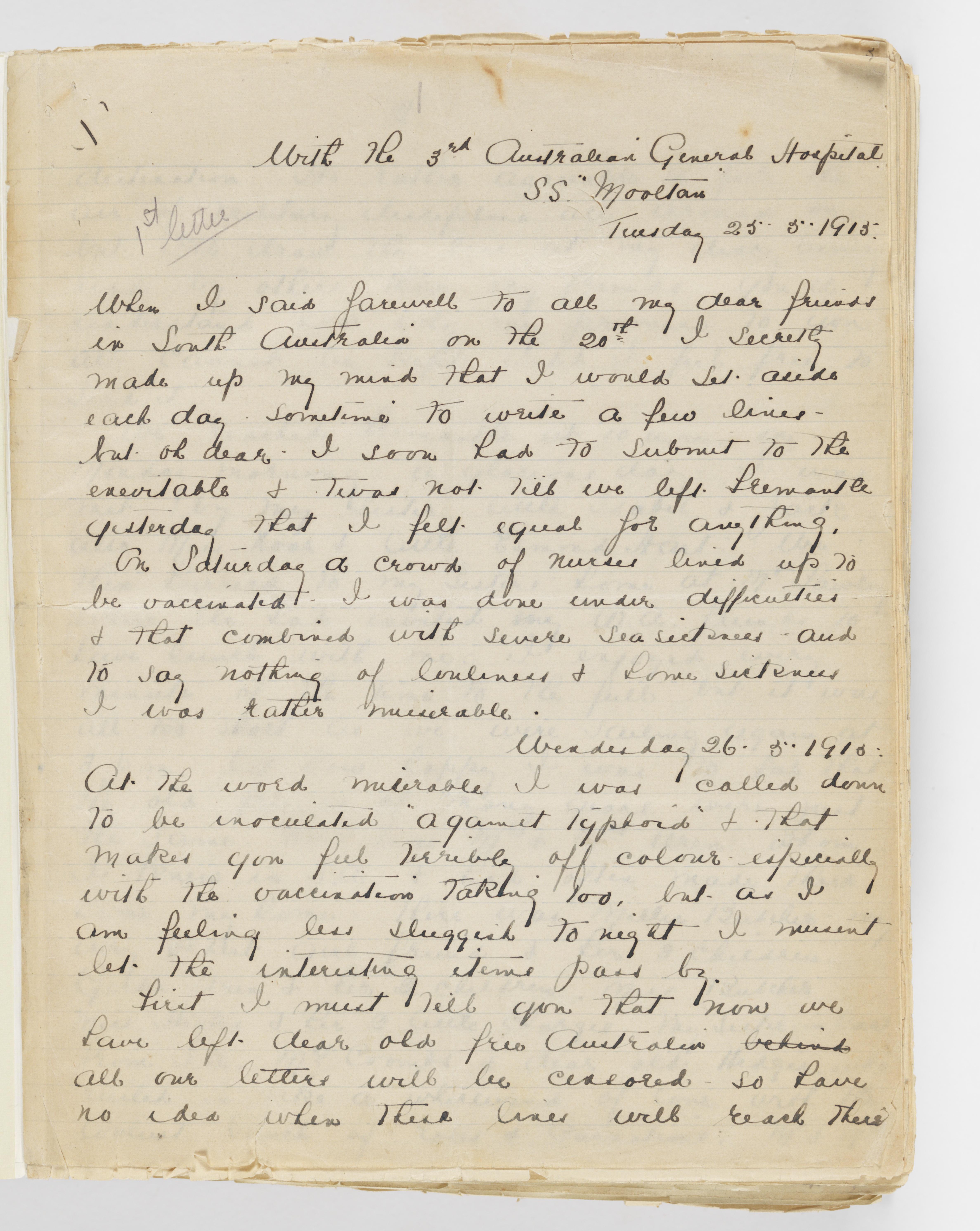

Serving as a nurse with the 3rd Australian General Hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos, and later in France and England, Anne had seen some terrible sights. She was a great storyteller, who wrote frequent letters home to friends in Adelaide as well as keeping a diary.

Her stories began on board the Mooltan with medical colleagues. They had discovered a 12-year-old stowaway on board, ‘a little chappie called Reggie’ whose mother had died and whose father and brother were away at the war. Several nurses and Red Cross staff wanted to adopt him, but the Captain informed them he would be sending him back when they reached Sri Lanka.

Anne devoured each new experience, describing her adventures in Colombo, London, Alexandria and Cairo: ‘Everything was so interesting’. Like many of the visiting Australians, Cairo provided cultural fascination and excellent shopping:

… the centre of the bazaar quarter … this place seems to be devoted to everything that is oriental in the way of Alleys full of copper ware, brass-ware, gold & silver, precious & ornamental stones, Turkish slippers etc. It’s most fascinating & I take a delight in beating them down for the goods …

The hospital at Lemnos, where Anne arrived in mid-October 1915, comprised ‘rows of Marquees (as wards) & bell tents. We have beds for 1040 patients — though at present we have 1200 patients.

So some still are on Mattresses on the ground, they don’t mind though & seem perfectly contented.’ Patients arrived from Gallipoli, across the Aegean Sea, before the December evacuation. They were wounded or suffered illnesses such as dysentery, jaundice and frostbite.

By January 1916, Anne reported, 7400 patients had been treated and ‘the death rate percentage was only 2½ which was considered excellent’. ‘Not one of the staff have died,’ she added, ‘though many have been seriously ill & we are quite proud of that — by the way Colonel’s pet horse died also his kookaburra & our grey bonnets that we disliked so much, died a natural death there. Grey felt hats are on the way out from England for us — also more stylish grey coats.’

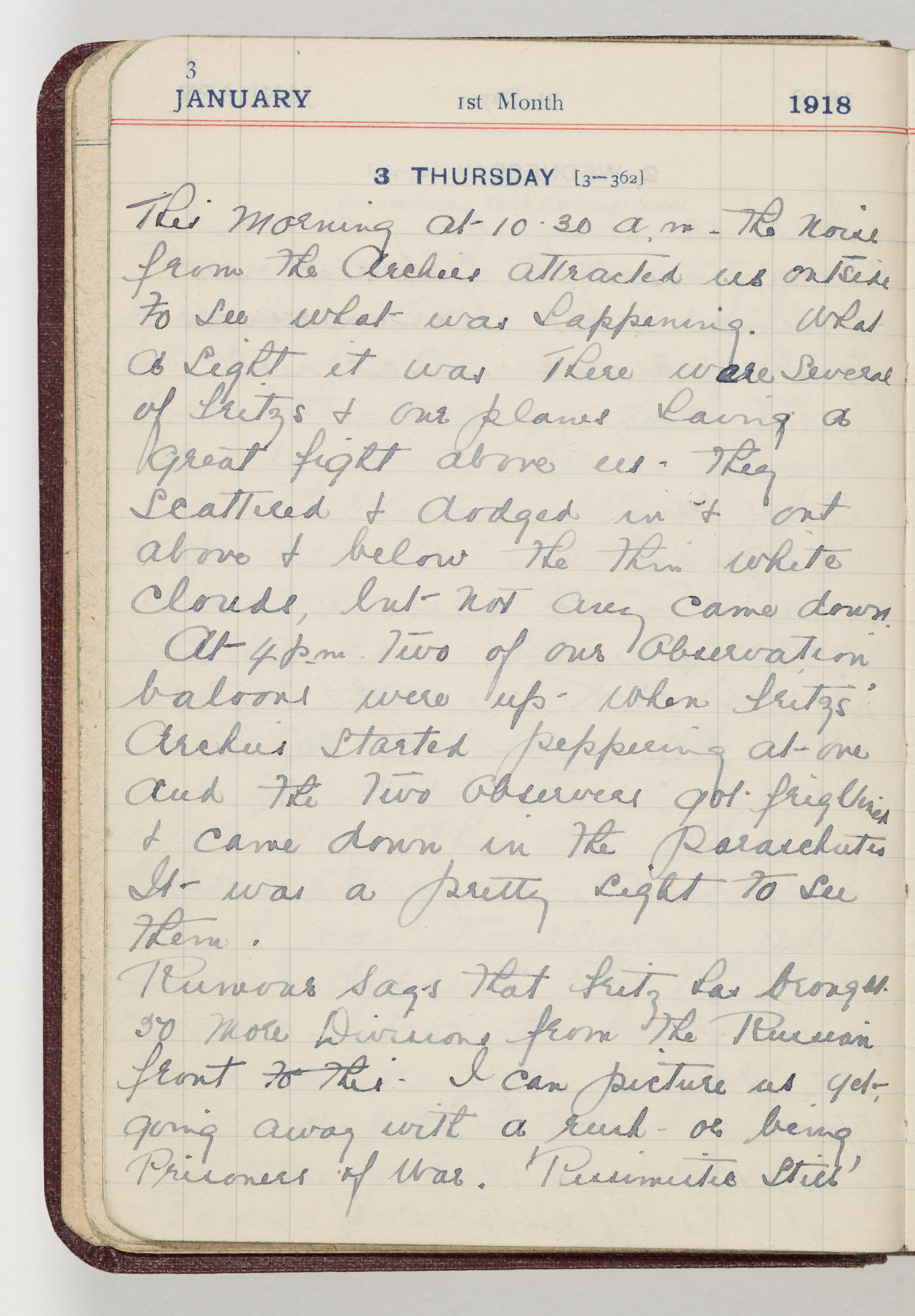

Two years on, Anne was still in the midst of war, this time serving on the Western Front at the 48th Casualty Clearing Station near Ypres. As 1917 turned into 1918, Anne was homesick and war weary. She had a cough and would be hospitalised in a few weeks’ time with the flu:

Time lags. The beginning of a New Year. Twas heralded in for us by the sound of shells from the enemy and the sounds of our guns retaliating. All the Sisters stayed up but me … I was a bit homesick and got out some old letters and re-read them. I was tired too. Then the shelling kept waking me — And my cough was troublesome, and I didn’t take Mrs Wiggs advice — Sit on the bed & smile but got sorry for myself & cried a bit — So the beginning of 1918 is not a promising omen for Anne.

Anne Donnell returned to Australia in early 1919. Heading home on the troopship, she wrote about seeing the Southern Cross in the sky. Prior to disembarking in Perth she remarked on the ‘uncommon scent but we fancy it savours of trees — so we just call it the smell of Australia’.

Elise Edmonds & Peter Cochrane

References:

Diamonds in the dustheap: Diaries from the First World War by Peter Cochrane, Humanities Australia, No. 6, 2015.

Collections:

Donnell papers, 1915-1919 / Anne Donnell

Series 01: Anne Donnell circular letters, 25 May 1915 - 8 July 1918, MLMSS 1022/Item 1

Series 02: Anne Donnell diary, 29 December 1917 - 31 January 1919, MLMSS 1022/Item 2

Hutton war diaries, 1915-1918 / John Thomas Hutton, MLMSS 1138