Children executed from 10 to 4

I’m often amused observing photographers from specialist child photography studios struggling with miniature charmers (and their doting parents) at suburban shopping malls. It soon becomes apparent that plonking even ‘the most beautiful baby in the world’ among colourful studio props and using expensive photographic equipment, complete with synchronised umbrella flashes and instant playback, is no guarantee of success. The simple truth is that photographing small children possessing small attention spans has always been a problem.

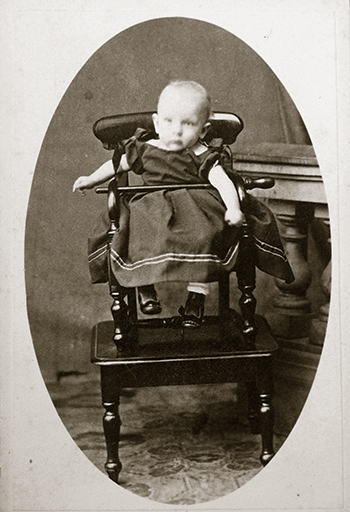

In the nineteenth century , exposures were rarely fractions of a second and it was common for portrait photographers to charge extra for infants under five and even ‘double price’ for children under four years of age, reflecting the failure rate due to subject movement. They also resorted to seating children in special posing chairs and clamping their subject firmly in place to ensure immobility.

, exposures were rarely fractions of a second and it was common for portrait photographers to charge extra for infants under five and even ‘double price’ for children under four years of age, reflecting the failure rate due to subject movement. They also resorted to seating children in special posing chairs and clamping their subject firmly in place to ensure immobility.

See left: Llewellyn Wheatley struggles to escape at J Uren’s studio, Kapunda.

Some chairs had a hole in the back, through which a crouching mother could place an arm to calm her offspring. At times, the resultant image would feature a disembodied adult arm steadying what seems to be a blur of flailing limbs.

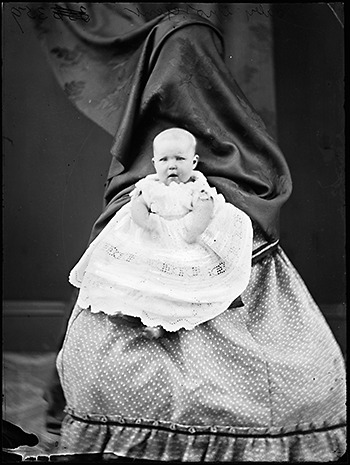

The American and Australasian Photographic Company’s Hill End studio did not have a specialist posing chair for children. Nevertheless, A&A studio photographers managed to steady their smaller clients by placing them in the comfort of their mother’s lap. The presence of the mother was concealed beneath dark cloth and later the image was cropped to mask her being there. However, seeing the whole negative gives the game away.

The American and Australasian Photographic Company’s Hill End studio did not have a specialist posing chair for children. Nevertheless, A&A studio photographers managed to steady their smaller clients by placing them in the comfort of their mother’s lap. The presence of the mother was concealed beneath dark cloth and later the image was cropped to mask her being there. However, seeing the whole negative gives the game away.

See right: Alice Grotefent held by her mother Jane (behind curtain.) Holtermann negative G 359, box 15.

Because of the poor light sensitivity of early photographic emulsions, photographic studios in the 1870s needed lots of light and most had glass roofs with shades to regulate the sunlight. Exposures were estimated according to cloud cover and the time of day, with shorter exposures being possible during the bright period around midday. Consequently, portrait studios in the 1870s regularly advertised that children would only be photographed between 10am and 2pm.

Despite the development of faster photographic emulsions later in the century, the problem continued. As late as 1895, the Half Crown studio in Sydney had a sign above the door, proclaiming “Children Executed from 10 to 4”, an idea which can only have encouraged patronage.

Words by Alan Davies.