Feminist, economist, sportswoman and pioneer.

At a time when women were more readily praised for domestic virtues than academic or professional achievement, Betty Archdale — whose papers are in the Library’s collection — brought to the conservative heartlands of Sydney a passionate belief in the importance of women’s education and their role in civic life.

In 1958, Archdale was appointed headmistress of Abbotsleigh, an exclusive girls’ school in Wahroonga on Sydney’s north shore, despite a lack of direct experience in secondary education. Then in her early 50s, and having excelled in the sporting, military and professional spheres, her personal achievements seem a natural outcome of her early upbringing, which was filled with strong female role models.

Born in London in 1907, Helen Elizabeth (Betty) Archdale was the only daughter of famed feminist Helen Archdale. In 1869, her grandmother had been one of the ‘Edinburgh Seven’ – the first group of undergraduate female students to matriculate to any British university. Betty’s godmother was the renowned suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst and Betty’s earliest memories included visiting her mother at Holloway Prison when she was jailed for acting on her suffrage principles.

Betty attended her mother’s old school, St Leonard’s, in Scotland — one of the first girls’ schools to emulate exclusive boys’ schools like Eton and Harrow in fostering leadership abilities and aiming for university entry — she excelled at sport, became Head Girl and matriculated with ease. Keen to broaden her horizons, Betty chose to study at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where she gained a degree in economics and political science. On her return to England, she completed bachelor’s and master’s degrees in international law at London University and was called to the bar in 1937 (one of only 50 women at the time), practising at Gray’s Inn until the outbreak of the Second World War.

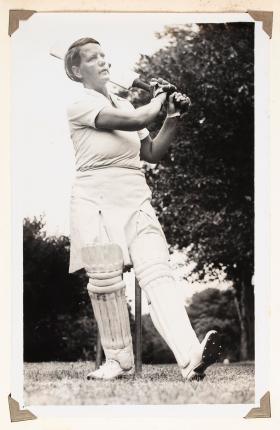

Betty also travelled to Australia in 1934–35, as captain of the first English women’s cricket team to tour internationally. The team selectors saw her as the perfect leader and the Australian press praised her as a fair and professional player in the wake of the acrimonious ‘Bodyline’ series. She formed enduring friendships with women she met on the tour and who she identified as ‘independent types’, like Sydney Morning Herald journalist Kath Commins, Margaret (Peg) Telfer (later Registrar of the University of Sydney), architect Barbara Peden and her sister Margaret, captain of the Australian cricket team from 1934–37.

In wartime, Betty served with the Women’s Royal Naval Service (the ‘Wrens’) as officer in charge of the first group of telegraphists sent to Singapore in 1941. Evacuated just before the Japanese invasion, further tours of duty took her to the Middle East, Africa, India, and the Pacific.

Awarded the MBE in 1944 for her outstanding service, she was promoted to first officer and sent out to Melbourne in charge of all the WRNS stationed in Australia. Betty had fully intended to return to England but, realising the struggle it would take to establish herself as a barrister in post-war London, cricket alumnus Barbara Peden (now Munro) encouraged her to apply for the Principalship of Sydney University Women’s College.

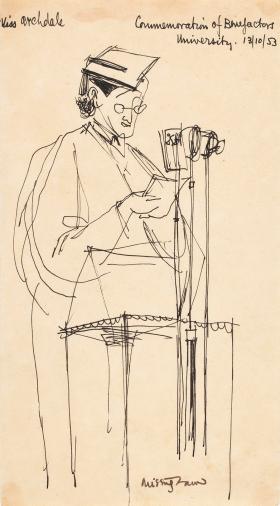

At a time when less than a fifth of the students at Sydney University (then the city’s only university) were female, she described her Women’s College role as ‘an administrator with an academic bias’, and encouraged the 90 female residents, from all sorts of backgrounds, to pursue equal opportunities with men in work and study.

It was also during this time that Betty and her brother, Alec, made the revolutionary move towards a more self-sufficient lifestyle, building a rammed-earth house together at Galston, north west of Sydney.

Through the 1960s and 70s, Betty became a radio and television personality and much sought-after social commentator. In active retirement her influence continued to spread, and she served on the boards of many organisations and wrote two books. She received an honorary of Doctor of Letters in 1985, was voted a ‘national living treasure’ in 1998, and was elected as one of the first 10 women honorary life members of the Lords Cricket Ground by the Melbourne Cricket Ground a year before she died, in 2000.

Betty Archdale made good use of the opportunities secured by the first generation of women’s movement pioneers — not only through her exceptional work in women’s education and women’s sport but also by making a niche for herself in the wider community. ‘I just happen to be lucky enough to be able to follow my own convictions,’ she reflected.

Margot Riley

Curator, Research and Discovery