The Flame

The Olympic torch relay, and its climactic cauldron-lighting, is inextricably woven into the lore of The Games. One could be forgiven for imagining the ritual as handed down from Zeus on Mt Olympus and enshrined in Pindaric Ode before finally flickering out and lying in wait for two millennia. Catching fire anew with the 1896 revival of the Olympic tradition in Athens, the cross-country relay functions as a perfect symbol of the ‘new and mighty ally’ for world peace that the Games promised to deliver.

The truth however is altogether more earthbound. The Olympic flame was not lit until the Amsterdam Games of 1928, and the torch relay from Olympia to the host city was not run until Berlin in 1936. It did not take long for this procession to move from the celebratory to the hallowed, with that inaugural parade also introducing the sacramental lighting of the flame from the sun’s rays at the temple of Hera. Before long the Olympic torch ceremony, relay and cauldron had arrived as a fully formed ritual, the torch proceeding from Olympia and never being allowed to extinguish until the closing of that year’s Olympiad.

If the lore developed quickly, then so too did the logistical challenges involved in completing the relay. As the reach of the Games grew increasingly global, more extreme measures were required to ensure the flame’s survival. Multiple fires were lit as back-ups, a team of guards carefully watching over each. The flame was transferred from torch to miner’s lanterns for aeroplane journeys, satisfying killjoy aviation officials and their antipathy toward naked flames.

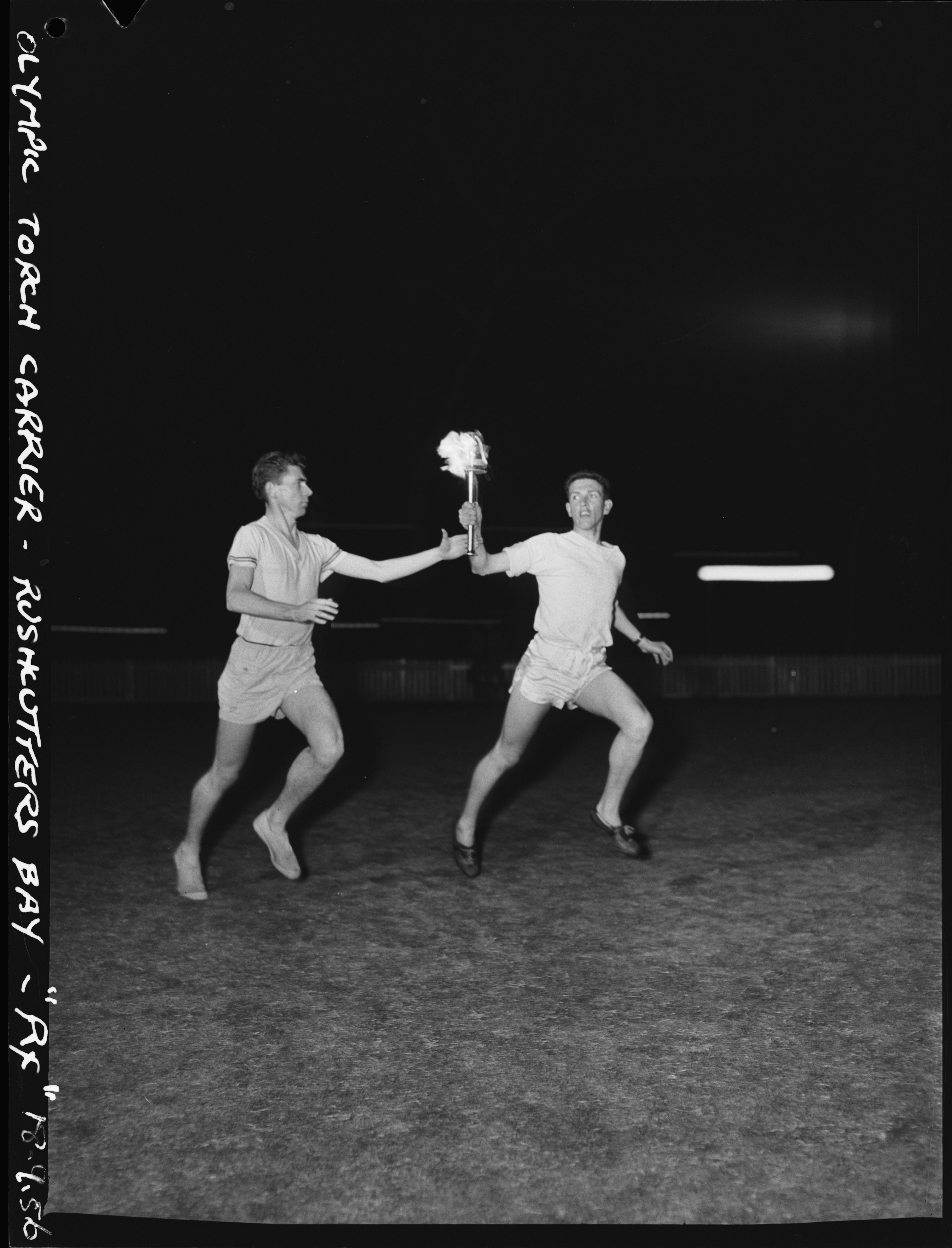

Over the years the relay course grew ever longer, the cauldron-lighting ever more elaborate. The honour of carrying the torch was much coveted; the greatest honour of all was to be the last to carry it, a nation’s chosen representative to light the Olympic cauldron. It was so prestigious that it became a closely guarded secret at each Olympiad. Melbourne’s 1956 representative Ron Clarke recalls having to wear a balaclava at the dress rehearsal to maintain the mystery.

Sydney’s experience proved no exception. The journey from Olympia to Homebush was at that point the longest journey the Olympic flame had embarked upon. The papers of Australian relay coordinator Di Henry, held at the State Library of NSW, are a testament to the monumental challenges involved in pulling off such a feat of logistics. The collection, comprising 10 boxes, includes torch designs, maps and documentation of the relay route, as well as over 300 video recordings of the running of the Olympic and Paralympic torch relays. The torch passed through 12 countries before beginning its Australian leg at Uluru, travelling through every state before arriving at the Opening Ceremony. Along the way it would travel by camel in Broome, on skis at Thredbo, and even underwater at the Great Barrier Reef. Regrettably a leg to be completed via bungee rope at Queenstown, New Zealand, was deemed a jump too far.

All through that Olympic year one question persisted: who will light the cauldron? Four-time gold medallist Betty Cuthbert was an early and consistent favourite, odds-on with the bookmakers and never far from speculation. Swimming legend Dawn Fraser was another obvious choice, and as the months went on the rumours grew ever more outlandish: Samantha Riley, who had missed selection for the Australian swimming team; noted non-Olympians Greg Norman, Tony Lockett and Donald Bradman; even Nelson Mandela, who was in Sydney during the Games for predominantly non-Olympic business. Finally, heard in whispers that grew louder and more insistent as the ceremony drew nearer, came the name of a world champion runner from Mackay, Catherine Freeman.

On the night of Friday 15 September 2000, before a crowd of 110,000, the Olympic Stadium announcer dispelled the first of those rumours as Betty Cuthbert’s name was called. The 62-year-old made her way to the running track to a loud cheer. No male hand would touch the torch from here — it was now time for the Golden Girls. Raelene Boyle, perennial Olympic bridesmaid, did not get her own relay leg inside the stadium. In a stirring moment, she pushed Cuthbert’s wheelchair along the track towards Dawn Fraser — another theory quashed. Fraser in turn passed the torch to Shirley Strickland de la Hunty, and she to Shane Gould. For the penultimate relay leg, with the imposing white stairway to the cauldron approaching, it was Debbie Flintoff-King, the last Australian to win Olympic gold in a running event at the Seoul Games in 1988.

And then — the revelation. It was Cathy Freeman’s moment. The assembled crowd erupted. This was Australia calling its shot, ordaining its newest Golden Girl a week before she took her first competitive strides at the Games. The symbolism of Australia’s last running champion passing the baton — literally — to its presumptive next did not escape many. Was it fair to burden her with such expectation? Were her shoulders broad enough to carry the hopes of a nation behind her? If she bore the weight heavily it was not betrayed by her face as, smiling broadly, she raised the torch in a salute to the crowd, carried it up the steps, and set the cauldron alight. The Games of the XXVII Olympiad had officially begun.

Ten days — and 49.11 seconds — after lighting the cauldron, Olympic champion Cathy Freeman sat in silence on the track, her face equal measures relief and disbelief. It was an emphatic victory, cheered on by an estimated 8.7 million around Australia. Michael Amendolia’s stunning image perfectly encapsulates the moment. In a crowd of 110,000, Freeman cuts a lonely figure. The victory, and the glory, are hers alone. Returning to her feet, Freeman begins to walk, then jog. Finally she dances on the spot, an awkward jig of unrestrained joy, as if allowing herself to believe at last that it was real, that this happened. The torch had been physically passed to Freeman at the Opening Ceremony; now she had claimed it metaphorically too.

If the glory remains Freeman’s, the moment belongs to us all. In commentary, Raelene Boyle eloquently captured the mood: ‘She’s made the country stand as one and be proud’. She had done that twice in the space of a fortnight. Completing her lap of honour Freeman was grabbed by a television reporter who asked what she thought when she looked up at the burning cauldron atop the stadium. Freeman’s apt response was prefaced by her signature laugh: ‘I lit that’.

Michael Adams, Information and Access.

References

Goldblatt, David, The Games: a Global History of the Olympics, London: MacMillan, 2016, p 38

Horne, John & Whannel, Garry, Understanding the Olympics, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Routledge, 2016, p 67

Howard, Bruce, 15 Days in ’56: The First Australian Olympics, Pymble, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1995, p 23

International Olympic Committee, Factsheet: The Olympic torch relay, October 17, retrieved 4 July 2021

Wilson, Bruce, ‘Flame a link with the old world’, The Daily Telegraph, 5 June 2000, p 4

Wilson, Bruce & Sprawson, Eleanor, ‘The journey begins- celebrating the lighting of the Sydney 2000 Olympic torch’, The Daily Telegraph, 11 May 2000

De Brito, Kate, ‘Burning Question’, The Daily Telegraph, 9 September 2000, p 43

Sportcal.com, Press Release: ‘Nelson Mandela at the Sydney Media Centre’, 3 September 2000, retrieved 5 July 2021

Olympics.com.au, ‘Olympians’, retrieved 5 July 2021

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqio9yoaM6M retrieved 5 July 2021

OlympicTalk, ‘How Cathy Freeman came to light the Olympic cauldron in Sydney’, NBC Sports, 15 September 2020, retrieved 5 July 2021