Aboriginal rights and freedoms: the 1967 referendum

Students examine the evolution of the Australian Constitution and what it reveals about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights and freedoms at various points in our history.

Key inquiry question #1

What does the drafting of the Australian Constitution reveal about the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the lead up to Federation?

Key inquiry question #2

What were the impacts of the 1967 Referendum on the Australian Constitution and how have these changes affected the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders?

Learning intention

Students are learning to:

- Recognise the state of the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people prior to 1967

- Understand how the Australian Constitution impacted on the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Interrogate sources in order to extract relevant information in response to historical inquiry

Success criteria

Students will be successful when they can:

- Outline defining characteristics of the background to the struggle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for rights and freedoms before 1967

- Describe the impact of the Constitution, as it was brought into power in 1901, and the changes to the constitution, as affected by the 1967 Referendum, on the rights and Freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Use evidence from historical sources to justify their findings

Student Activities

The Constitution

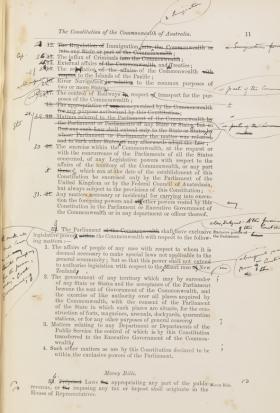

Students investigate the original drafting process for the Australian Constitution, looking closely at sections 127 and 51 and the impact of these on the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

NSW Syllabus for the Australian Curriculum History K-10

HT5-3 Explains and analyses the motives and actions of past individuals and groups in the historical contexts that shaped the modern world and Australia

HT5-6 Uses relevant evidence from sources to support historical narratives, explanations and analyses of the modern world and Australia

Background to the struggle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for rights and freedoms before 1965, including the 1938 Day of Mourning and the Stolen Generations (ACDSEH104)

Students:

- Outline the rights and freedoms denied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples before 1965 and the role and policies of the Aboriginal Protection Board, e.g. the control of wages and reserves

The significance of the following for the civil rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples:...1967 Referendum... (ACDSEH106)

Students:

- Outline the background, aims and significance of key developments in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ struggle for rights and freedoms

Analysis and use of sources

- process and synthesise information from a range of sources as evidence in an historical argument

Explanation and communication

- develop historical texts, particularly explanations and historical arguments that use evidence from a range of sources (ACHHS174, ACHHS188, ACHHS192)

Cause and effect: events, decisions and developments in the past that produce later actions, results or effects, eg the reasons for and impact of the struggle for rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Significance: the importance of an event, development, group or individual and their impact on their times and/or later periods

Learning across the curriculum

Cross-curriculum priorities

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures

General capabilities

- Ethical understanding

- Literacy

Other

- Civics and citizenship

Background notes for teachers and students

Status of Aboriginal Australians prior to 1967

Government policy around Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia had gone through several phases in the lead up to the Federation of Australia in 1901. At the time, a period of ‘protectionism’ was in full swing, having begun in the late 1890s. Protectionism was characterised largely by segregation, and was to be the main driver of government policy in regards to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples until the 1950s. When the Australian constitution took effect on 1 January 1901, each individual state acquired the primary lawmaking power over Aboriginal people. Consequently, the legal status of Aboriginal people shifted from British subjects to wards of the state. In each state, a Chief Protector was appointed. Their role was to administer the laws relating to Aboriginal people. Colonial and State Aborigines Protection Acts were passed in each of the states, including the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (NSW).

The Aborigines Protection Act would be the main piece of legislation governing the lives of Aboriginal people in NSW from 1909 to the 1960s. The Act vested power in the Aborigines Protection Board over all reserves in the State, enabling them to do such things as move Aboriginal people out of towns and into reserves or ‘missions’, install managers and other staff on these reserves, and block the movement of people in and out (including non-Aboriginal visitors). In later amendments, the Act allowed the Board to remove children of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal parents from their homes and place them into homes where they would be raised ‘white’. This was one of the changes in policy that heralded the official start of a period of ‘enforced assimilation’ for ‘part-Aboriginals’. In 1940, the Aboriginal Welfare Board replaced the Aborigines Protection Board, and continued to work under the new policy direction of ‘assimilation’, closing reserves and encouraging people to move into the towns.

Policies of assimilation governed the lives of Aboriginal people from 1937 to the 1960s. In 1937 the Commonwealth Government held a conference on Aboriginal affairs, during which it was agreed that Aboriginal people ‘not of full blood’ be ‘assimilated’ into the community. Under these policies, Aboriginal people were expected to live like ‘white’ people, adopting European cultural practices and language and leaving their own culture and language behind. During this period, the rate of forced removal of Indigenous children from their families increased. In addition to the required rejection of their language and culture, a range of other rights and freedoms continued to be denied to Aboriginal people during this time including where they lived, whom they married, and how they spent their earnings. From the 1940s, Aboriginal people could apply for exemption from the Aboriginal Protection Act, whereby they would ‘cease to be Aboriginal’. Any person holding such a certificate of exemption had to live under certain rules, including living like a ‘white’ person, displaying exemplary behaviour, ceasing all contact with non-exempt Aborigines other than immediate family, and carrying their certificate with them at all times. In return, the certificate entitled them to such things as the freedom of movement, the right to drink alcohol and the right to own land.

Aboriginal-led resistance since 1770

The Aboriginal people of Australia had been leading resistance efforts, both within and outside European legal structures, since Cook’s arrival in 1770 at what would come to be known as Botany Bay. At this time, Joseph Banks recorded in his journal (Joseph Banks – Endeavour journal, 15 August 1769 – 12 July 1771) that the Gweagal people they encountered “resolvd to dispute our landing to the utmost tho they were but two and we 30 or 40 at least”. He went on to recount how, despite being initially startled by the Europeans firing a musquet over their heads, they quickly “renewd their threats and opposition”. This journal can be viewed in its entirety through the State Library of NSW’s catalogue or a typed transcription. Banks’ recollections of the landing at Botany Bay beginning on page 375.

Resistance efforts, led by Aboriginal people, continued from when the First Fleet landed in 1788, and often saw violent conflict break out as Aboriginal people took a stand against the occupation of their land and destruction of their communities and ways of life.

One of the most prominent resistance efforts within European legal structures, widely regarded to be the beginnings of contemporary Aboriginal political movement, was the 1938 Day of Mourning. On 26 January 1938, whilst most Australians were celebrating the sesquicentenary of European settlement, about 100 Aboriginal men, women and children from around Australia gathered at a venue on Elizabeth Street in Sydney, known as Australia Hall. In summarising the tone of the protest, organisers stated “the 26th of January, 1938 is not a day of rejoicing for Australia's Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years of so-called 'progress' in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.” The protestors intended to bring awareness of their plight to non-Indigenous Australians and have the Protection Boards dismantled, and rallied for full citizen rights for Aboriginal people. The event led to major reforms of the Protection Boards and contributed to bringing about the 1967 Referendum. The 1938 Day of Mourning is recognised as the first ever national Aboriginal civil rights gathering.

Pursuant to the Day of Mourning, the first edition of the newspaper The Australian Abo call: the voice of the Aborigines (the Abo Call) was published in April 1938. The Abo Call was in effect the Association’s monthly newsletter. Whilst it lasted for only six issues, owing to financial difficulties, the Abo Call is said to be the first Australian publication devoted to Aboriginal issues. Although the term ‘Abo’ is considered derogatory today, it was not always taken to be so and probably had a less pejorative connotation in 1938.

1967 Referendum

Whilst Aboriginal Australians had finally been granted the right to vote in Australia in all jurisdictions in 1962 with the passing of the Commonwealth Electoral Act (Note: Enrolment to vote, however, was not compulsory for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people despite being compulsory for all other Australians in national elections since 1924), it was not until the 1967 Referendum that the Commonwealth was able to create laws for Aboriginal Australians and count Aboriginal people in the national census (like all other non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.) The culmination of a long campaign, driven by many Indigenous and non-Indigenous organisations and people, the 1967 Referendum was a turning point in race relations in Australia. Over 90% of Australians voted ‘yes’.

Additional Material

From the collections of the State Library of NSW

- An article on “Changing Policies Towards Aboriginal People” from the Australian Law Reform Commission

External (to the collections of the State Library of NSW)

- A website from the City of Sydney council called Sydney Barani

- Right Wrongs, a website from the ABC