Tall and Trimmed by Mark Dapin (extract)

All things must pass, and even statues have to know when it's time to go.

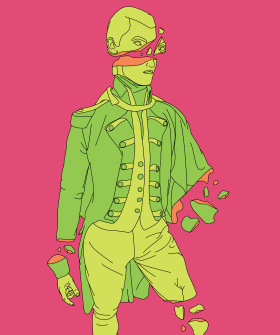

The only certainty in the life of a statue is that one day it will fall. That process has accelerated recently, as the re-energising of the Black Lives Matter movement has carried in its wake a fresh wave of incidents where statues have been damaged, displaced or demolished to highlight their namesakes’ complicity in the slave trade. The toppled dead men — and they’re always men — have included Confederate generals in the US and the merchant Edward Colston in the UK.

President Trump has accused protestors of a ‘merciless campaign to wipe out our history’, although it’s difficult to see how mercy — or cruelty — could be afforded to a piece of bronze, marble or cast zinc.

In Australia, calls have been made to reassess the legacies of statued luminaries such as James Cook, Lachlan Macquarie, James Stirling and Thomas Mitchell in the light of their impacts on Indigenous civilisation. The base of a statue of Cook was graffitied in Hyde Park, Sydney, and a figure of Stirling was sprayed with red paint in the centre of Perth.

Even the State Library of NSW has been drawn into the curiously imagined ‘statue wars’. In March 1996 a bronze of explorer Matthew Flinders’ cat Trim was placed on a window ledge within pet-appropriate proximity of Flinders’ statue outside the Mitchell Library. Trim’s image was fashioned by the late Kiama artist John Cornwell — whose website offered similarly ‘masterly renditions’ of ‘your own loved companion’ — and was erected by public subscription of Trim’s ‘admirers’ in the North Shore Historical Society.

The journalist and author Paul Daley has suggested that Flinders’ Indigenous aide Bungaree may have played a more pivotal role in the mapping of Australia than his cat. But there are no statues of Bungaree and more public sculptures in Australia of animals than Indigenous people (or, for that matter, women).

Many Library visitors are enchanted by the statue of Trim but, rationally speaking (God forbid), it’s quite a strange idea to build a historical memorial to a cat, since cats have no more independent historical agency than statues. Whatever Trim’s achievements may have been, he certainly had no intention of circumnavigating Australia and no consciousness of having done so. That said, Flinders was tremendously fond of Trim and composed tributes to the animal in poetry and prose. This surely says more about Flinders than his cat, so perhaps the memorialisation of Trim does help us reach a more rounded understanding of the man.

In any case, nobody is asking for Trim to be removed from his perch — only for Bungaree to join him. But probably not on a window ledge.

Subscribe to Openbook to read the full story.