A conservator’s job is to advocate for all cultural material, throughout the whole exhibition process. We are responsible for caring for each item and facilitating access through display.

We work with the creative producer, curator and designer to deliver an exhibition’s story and vision, coordinating treatment of collection material where required, and working out how to mount each item in a way that’s both supportive and reversible, using archival materials only. We must ensure that environmental conditions are right for the long-term care of an item while it’s on display: an inert, pollutant-free display enclosure; stable relative humidity and temperature; and controlled lighting.

The scope of the Photography Gallery’s inaugural exhibition — all types of photographs from the 1840s through to the present day — offered a unique challenge: to display this vast array of historical formats in a similar manner, floating within a transparent contemporary structure.

One third of the 200 original images required some form of treatment. The priority is always to ensure an item’s structural stability. For works on paper, this might mean repairing a tear or hole, reducing cockling (rippled paper) or flattening curled or folded edges. We also consider when aesthetic intervention is appropriate; this might mean surface cleaning, stain reduction, or possible re-touching of missing imagery due to surface loss. In consultation with the curator, we might tone down these areas to blend in with the surrounding original surface, so the losses are not visually distracting.

If time allows, we carry out more complex treatments directed at longterm preservation, such as removing a photo from a non-original support or backing that is acidic and degraded. Our specialist conservators work across all photographic types, not just those on paper: daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, opalotypes and glassplate and cellulose-based negatives.

Many items already have their own display history. Historical photos were often adhered into albums, or onto a board with a window mount overlay, and then framed. Over a photo’s journey, its display format and use may change depending on its owners. By the time it reaches us, it may have become separated from its original window mount and frame, it may have a degraded or damaged non-original mount, or it may have been adhered to a backing board as part of an old restoration or an outdated Library storage system.

Before they are displayed, where applicable, photos are usually fitted with a new window mount to retain the original intent or historical use, or to cover an old support board that is visually distracting. A window mount focuses the eye on the image. For this exhibition, however, curator Geoff Barker wants to give the viewer a different experience — one like walking through a 3D version of the Library’s catalogue, where photos float in a transparent acrylic grid without any interpretive window mounting or framing. We affectionately came to refer to the display as ‘warts and all’! This different approach across such a range of photographs challenged us to re-evaluate our thinking around the presentation of historic material.

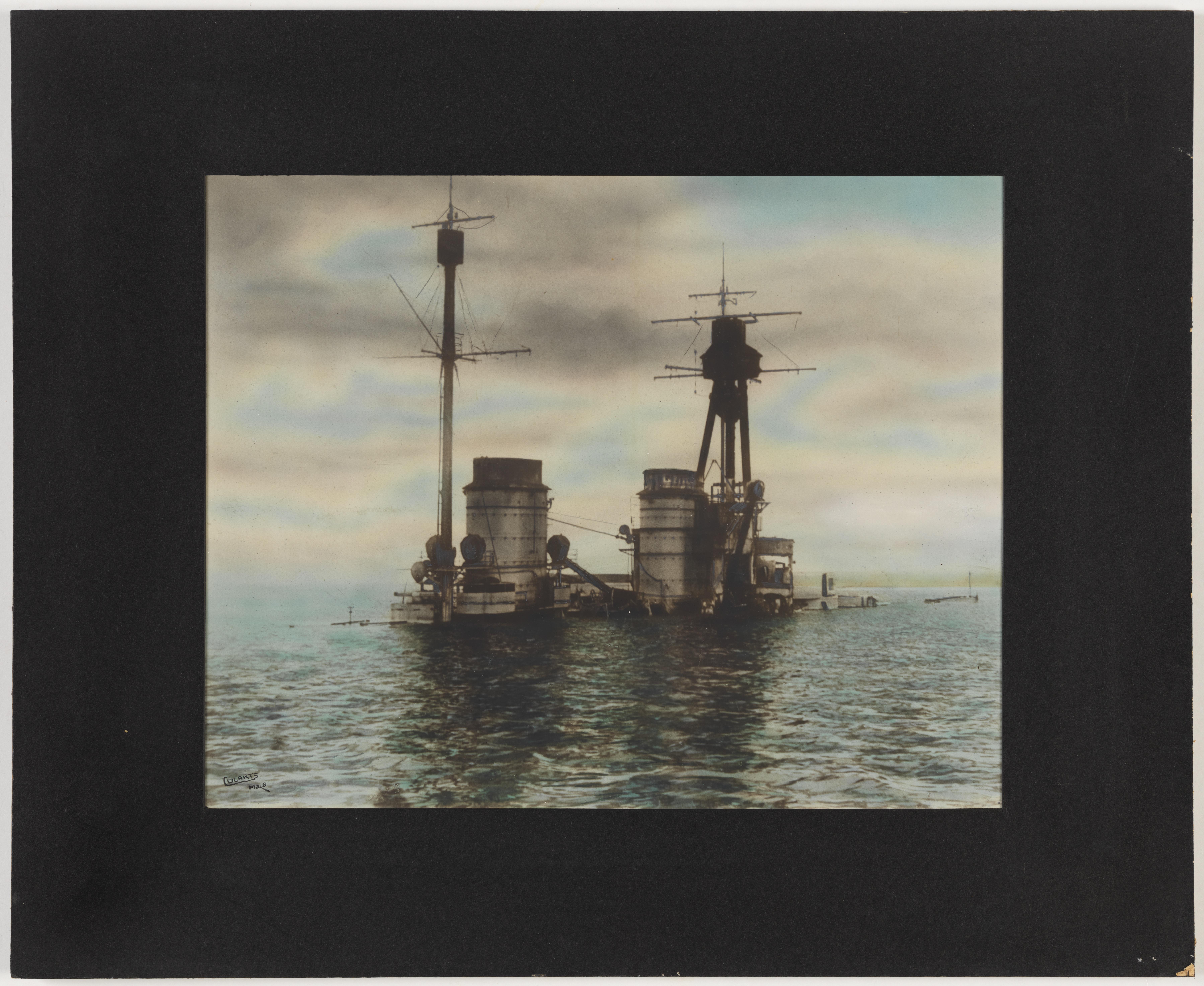

A good example of displaying an item as it exists in the collection, without interpretation, is this World War I image (see right), taken from the deck of HMAS Australia, of warships in line formation. It was produced in the 1920s by Colarts Studio in Melbourne. They would blow up small photos — often taken by frontline soldiers — into largerscale works that were then subtly coloured by air brushing, a new technique that had been recently developed in the United States. Colarts toured a collection of these photos around Australia. They were first adhered to repurposed standard boards and then window-mounted in black before being framed. This process is well documented, and we have several photos in the collection with original mounts.

In previous displays at the Library, we re-mounted the photos with black windows to recreate Colarts’ original aesthetic intention. The photo selected for the new Photography Gallery exhibition, however, no longer has an original window, but remains adhered to the original ‘scrap’ piece of mount board with an old standard border that is not properly aligned because it was not intended to be seen but, rather, covered with a window mount. The support board has tears from where the adhered window was removed. So, while the mount board support is part of the original photo’s display, it was never meant to be visible. In our exhibition, the photo will be presented as it currently exists in the collection without a window mount to cover the old backing board and focus the eye. Who can say which is more authentic?

We conservators collaborate with the designer, in this case Jemima Woo, to come up with mounting and support solutions within the overall exhibition vision. Items with different formats and materials, naturally enough, have different needs, so mounting everything in a relatively uniform manner can be a challenge. But we came up with a solution that will work for most photos. Each will be hinged to a white conservation mount board using conservationgrade adhesive and Japanese tissue hinges. The mount board is adhered to a thin piece of aluminium veneer which has a strip of L-shaped acrylic stapled to the top edge. The acrylic ledge has two holes that hook over two pins fixed into a 20 mm thick acrylic block that has been screwed to the wall. For some photos adhered to heavier board, such as the Colarts photo, an extra supportive edge is fixed to the bottom of the aluminium to provide a shelf. We also have custommade acrylic supports to display cased miniatures and open albums.

Mounting glass-plate and cellulosebased negatives that require back lighting for the image to be clearly visible — in other words, illuminating a negative — within this floating structure, required extra planning. Electroluminescent phosphor sheets are ideal for this as they are thin, can be cut to size and emit light. The phosphor does not generate heat and can be put on a timer to turn it off during closing hours. The plastic sheet is part of a layering system to reduce the light exposure behind the negative, which is placed within a custom-made acrylic support attached to the wall. The wire and transformer box can be hidden in the wall behind the item.

A good example of backlighting is with iconic photographer Frank Hurley’s Paget plates, the only colour plates from the Shackleton Antarctic expedition, 1914–1916. We’re familiar with lots of pictures of Shackleton’s expedition, but they’re reproduced contemporarily, through scanning or printing. There aren’t many that Hurley made himself, in part because he didn’t hold copyright: Shackleton did.

Because the Library holds the diaries that relate to Shackleton’s expedition, we can display the page where Shackleton records making Hurley break all the glass negatives, except for 120, the number he can carry with him on the boat back to Elephant Island and safety. When the Endurance got crushed by ice, Hurley had to dive into the water to rescue a container, soldered tight, containing his glass plates. He brought it back to Shackleton and they sat there one afternoon breaking all but the 120 plates, because Shackleton knew that Hurley would have tried to put extra plates where he wasn’t supposed to.

As challenging as it is, visitors will see why we wanted to show the Paget plates. Here we see Frank Hurley taking photographs under the bows of the Endurance during the Shackleton expedition.

This early method of colour photography has its own unique beauty when seen in glass-plate form. With no light, the plate looks almost black. With the addition of light on the left, the plate reveals its hidden treasure.