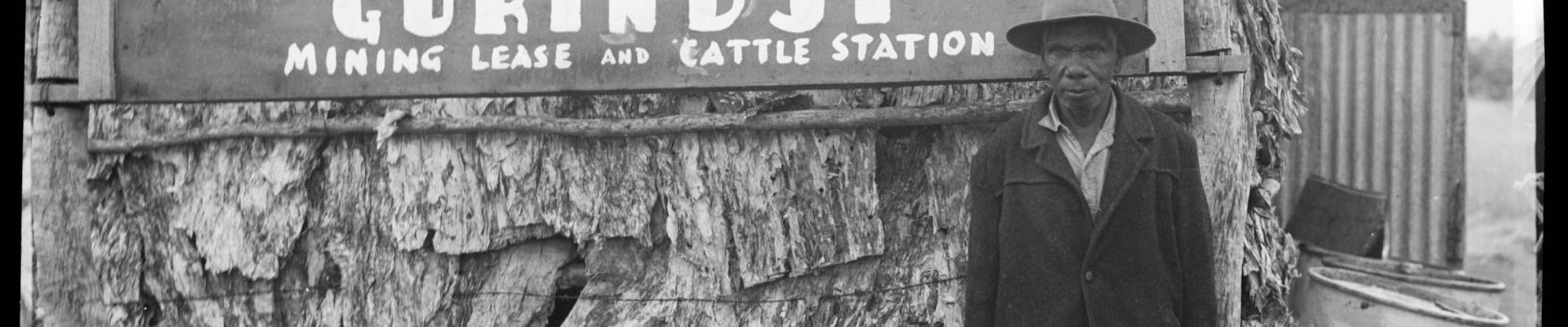

The Gurindji and their supporters

On 15 August 1975, at Wattie Creek in the Northern Territory, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam gave the Gurindji people of the Northern Territory legal title to their traditional lands. The scene, captured in a now iconic photograph, was the culmination of a long struggle by the Gurindji and their supporters.

The story of the Gurindji’s struggle for land rights — celebrated in the 1991 song ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’ by Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody — has become an important part of the folklore surrounding the struggle of Indigenous people for social, economic and political justice. The story of the people who supported the Gurindji is also fascinating.

As a university student at the time, I was part of the Sydney-based (Save the) Gurindji Campaign. The Mitchell Library holds the personal papers of a number of key people in the campaign including Hannah Middleton and Rod Williams. These papers provide a wealth of information about developments in the Territory and the national network of supporters.

Beginnings of the struggle

The Gurindji lands included the Wave Hill cattle station, over which the British Vestey company — a large international meat producer — held a lease that was not due to expire until 2004. Gurindji people worked on the property as stockmen, general hands and domestics. Anthropologists Catherine and Ronald Berndt had documented the very low wages and appalling working and living conditions of Aboriginal people on Vestey leaseholds in 1946, and by the 1960s the relationship between the station owners in the area and their Aboriginal workers was described as ‘feudal’.

In March 1966 the government removed a clause from the Cattle Industry (Northern Territory) Award which had prevented payment of equal wages to Aboriginal stockmen. But the changes were to be phased in over three years and would include a slow workers’ clause, which would allow an employer to pay workers at a lower rate. In protest, the Gurindji walked off Wave Hill in August 1966, and settled at Wattie Creek, known to them as Daguragu.

While working conditions were the catalyst for the walk-off, the Gurindji had a much wider aim: to regain ownership of the land and run their own pastoral operation. Uneducated in the ways of white political, legal and economic systems, and with limited English, the Gurindji would need outside help to challenge the existing order.

That wasn’t straightforward. The lives of Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory were controlled by the government, pastoralists and, to some extent, churches. Union organisers were kept away from them by law, the closest telephone was controlled by the Welfare Officer, and they had little privacy to send telegrams criticising the government.

The Gurindji had tried to strike before, but without outside support they had no option but to go back to work. In 1966, Darwin-based union and Aboriginal activists took up their cause, and Gurindji spokesman Captain Major (Lupgna Giari) travelled south to appeal to trade unions and the public for financial and moral support.

In July 1968 the government announced its decision not to grant land at Wattie Creek to the Gurindji. Although they continued to receive some support from unions and Aboriginal rights organisations, they had made little progress and were barely surviving at Daguragu.

Gaining national attention

Things changed significantly following a visit in mid-1970 by author Frank Hardy. Based in the Northern Territory as a soldier during the Second World War, Hardy had worked with local Aboriginal people (who were on the same Army wages as other employees). In 1970 he found the Gurindji starving and in desperate need of help.

After his visit, Hardy wrote three articles for the Australian about the plight of the Gurindji strikers. When people contacted him to offer support, he called a meeting at the Teachers’ Federation in Sydney that launched the Save the Gurindji Campaign. Expecting the campaign to last about three months, supporters adjusted their expectations when the Gurindji began to roll out more ambitious plans.

In order to avoid accusations of paternalism and to reflect the campaign’s collaborative intent, it dropped the words ‘Save the’ from its title in April 1971. The Gurindji were pleased to accept help as long as supporters did not demand control.

The struggle was driven by ABSCHOL, a student organisation that provided scholarships and support to Aboriginal people, which had sent a field team to investigate the Gurindji’s needs in December 1969. Support groups were established in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. In Sydney (and to a certain extent nationally) Frank Hardy continued to play an important and driving role as Chairman of the Gurindji Campaign. A number of key women in the campaign had been politicised, even radicalised, by the Vietnam War when their sons had been eligible for conscription.

Active support

The campaign drew on support from unions, church organisations, the anti-apartheid movement and political parties such as the Communist Party of Australia, Socialist Party of Australia and some elements of the Australian Labor Party. The Waterside Workers’ Federation levied its members $1 per head and, in early 1972 after a request by Gurindji leaders Vincent Lingiari and Donald Nungiari, sent $10,000 (the equivalent of $100,000 in 2015) to help the Gurindji fence off their land.

Teams of supporters visited the Gurindji to find out what they needed and to help procure food, transport, housing and a water supply, as well as sending teachers, builders and mechanics. English anthropologist Hannah Middleton went to live with the Gurindji strikers for six months in 1970, providing a channel of communication with the city-based support groups, and documenting their struggle in notebooks and photographs.

Back in the state capitals, support groups organised boycotts of Vestey butcher shops and products and continued to raise funds. They handed out leaflets at railway stations, held fundraising concerts and stalls at festivals, lobbied for donations, and sold donated artworks.

Campaign of influence

Gurindji leaders also came south on speaking tours. They were taken to Canberra to press their cause with government ministers. This had limited effect at the time, but it brought the Gurindji’s needs to the attention of politicians who were more supportive, especially members of the ALP. Building these connections and raising awareness was to play a major part in shaping government policy over the next five years.

As a student at the University of NSW and a member of ABSCHOL, I became part of the Sydney Gurindji Campaign and eventually joined the Coordinating Committee, becoming Minutes Secretary and writing most of the newsletters. I made two trips to Daguragu, first in 1970 with a group which included ophthalmologist Professor Fred Hollows, a pediatrician and a water engineer from Sydney; and then in 1971 with Campaign Secretary Jean Leu, student anti-racism activist Sekai Holland (later a member of the Zimbabwean parliament) and Brian Havenhand, National Director of ABSCHOL.

The Gurindji welcomed their ‘friends from down south’ (as they called us), showing us their cultural life, including the bush tucker and ‘sing sings’ at night, and inserting us into their ‘skin’ system of kinship and social control. Our skin names meant we had people to supervise us and duties to carry out.

Symbolic achievement

The Gurindji Campaign (and its Melbourne equivalent) was wound up at the end of 1973 after the Whitlam Government came to power and set up the Woodward Aboriginal Land Rights Commission.

In July 1974, thinking that the Government was not acting quickly enough to grant land rights to the Gurindji, several campaign members sent a letter to ‘All members of the Australian Government’ urging them to act. I was one of the signatories to this letter, a copy of which is in the Mitchell Library.

The real reason for the delay, however, was that Prime Minister Gough Whitlam wanted to hand the land over himself, and the event took place in August 1975.

The Gurindji struggle was part of what became the national land rights movement, with other symbols including the Yirrkala bark petition of 1963 and the Canberra Tent Embassy established in 1972.

The success of the Gurindji rested on the vision, resilience, and strength of the people and their leaders, among them Vincent Lingiari and Pincher Numiari. The Gurindji Campaign played a critical role, enabling the people to survive and continue their protest, and giving them resources to begin self-determination and draw on key government decision-makers in support of their struggle.

Dr Christine Jennett was the Library's 2014 CH Currey Memorial Fellow.