In 2021, in the middle of a COVID lockdown, the Library’s Multicultural Bulk Loan Service received a call from a woman whose 88-year-old father loved reading Mills & Boon romances in Italian. They lived in an ‘area of concern’ in Sydney, so not only was their local library closed, it was not offering click and collect services. Its ebook collections were in English and the gentleman was not tech savvy anyway. In desperation, his daughter contacted us to see if we could help. Usually, we only supply multicultural loans to public libraries, but we knew that if we sent a box directly it would provide comfort and entertainment for her father during a difficult time. She later wrote to us saying, ‘Thank you so much, you don’t know how much this means for my father and myself. Much appreciated from the bottom of my heart.’

Multicultural Bulk Loan Service,then and now | |

Languages in 1974 16 languages, 2300 items | Languages in 2024 43 languages, 69,000 items |

Arabic Danish Estonian Finnish Greek Hebrew Hungarian Italian Japanese Maltese Norwegian Portuguese Serbo-Croatian Spanish Swedish Turkish | Arabic Bengali Bulgarian Burmese Chinese Croatian Czech Danish Dutch Finnish French German Greek Gujarati Hebrew Hindi Hungarian Indonesian Italian Japanese Korean Macedonian Maltese Nepalese Persian/Farsi Polish Portuguese Punjabi Russian Serbian Sinhalese Slovak Spanish Swedish Tagalog Tamil Telugu Thai Tibetan Turkish Ukrainian Urdu Vietnamese |

Providing books to readers in their own languages via public libraries across NSW can be a transformative experience. The Multicultural Bulk Loan Service may have had different names over the years but has always been incredibly popular, right from when it was first launched in 1974. We live in one of the most diverse states in Australia — more than 29 per cent of the NSW population was born overseas and over 280 languages are spoken at home — so the service is crucial.

In 2021, with Charles Sturt University, we undertook research looking at the value of reading in a first language. It showed how important this is for migrants, particularly for relaxation — living and working in a second language can be mentally exhausting. Reading in a native language can be a deeply emotional experience that helps people retain a connection with their culture and enhance pride in their heritage. One of our research participants commented, ‘Eight hours in my workplace speaking English all the time means when I see books in Persian it feels good. I can just calm down, not think about it.’ National and state-based migrant associations seek to maintain their culture and promote the survival of their language, so access to books in their language strengthens connections. Also, for those Saturday Schools that teach community languages, access to books through local libraries is a fundamental resource.

Colleagues in public libraries to whom we supply books often tell us that their readers are amazed not only that the service exists, but that it is free. They have shared stories about individual readers, and the books they love, in languages from Czech to Japanese, Telugu to Persian. The librarian in Gilgandra, for example, told us about an older lady who was born in the Netherlands but came to Australia as a child with her parents. One day in the library, she quietly asked if it was possible to find books in Dutch. The librarian requested large print novels in Dutch from the Library’s Multicultural Bulk Loan Service and the woman was delighted to be able to read romances and family sagas in her first language.

Another librarian in Wagga Wagga told us that one of their regular Croatian-language borrowers had been struggling with cancer for some time. Reading books in Croatian and Serbian in his favourite genres — crime and suspense — helped with the difficulty of being ill. The librarian said, ‘He has always been a great reader, and being able to get books in his own languages provides distraction, comfort and relief.’

Strathfield Library in Sydney frequently requests books in Korean for that community who, when asked, say, simply, that reading books in Korean makes their lives better. Seniors in particular, for whom English can be a big barrier, say that they feel welcomed knowing they can borrow Korean books and magazines from the library and that doing so reduces feelings of isolation. One library customer who migrated to Australia as an adult said that reading books in Korean gives him emotional stability. As much as he loves his Australian life, he sometimes misses the Korean things that are a part of him. He reflected that reading is different to speaking Korean because reading boosts his Korean literacy and exposes him to information and trends back home.

As well as reflecting on the impact of the Multicultural Bulk Loan Service in the present, the service’s 50th anniversary offers the opportunity to reflect on its history. In the early 1970s, responsibility for providing books in different languages lay with public libraries, which purchased their own collections in response to demand from their communities. Some purchased books in a particular language as part of the Sydney Subject Specialisation Scheme, a cooperative effort by public libraries to ensure that in-depth reference and fiction collections were available to their readers. Nevertheless, a 1972 survey of NSW public libraries by the Library Association of Australia found that the provision of foreign language collections was ‘quite inadequate to meet the cultural and recreational needs of migrants’. It recommended the establishment of a centralised service.

In 1974, then State Librarian Russell Doust took the recommendation on board. That year, the Library Council’s annual report noted that ‘Preliminary discussions have commenced on a proposal to establish a central pool of foreign language books … available for loan through participating libraries … This is a service for which the Council sees a clear need and it believes that the State Library must play a significant part.’ The Library had been sending boxes of reference books to country libraries to support their needs since the 1890s, but changing demographics as a result of shifting immigration policies meant that libraries were struggling to keep up with the growing demand for resources in different languages.

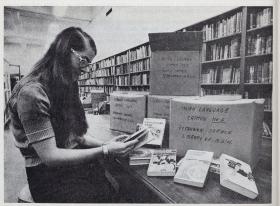

In 1974, the State Library launched the Foreign Language Lending Service with the stated intention of ‘providing books in less common languages to all libraries, and books in common languages to those who have no way to meet local demand’. At first, public libraries could request books in 16 languages, mainly from European and Middle Eastern countries. Japanese was the only Asian language initially available. New languages were introduced each year in response to community demand, and by the mid-1980s the service provided books in over 40 languages.

These new languages reflected global events. For example, the Indo-Chinese conflicts of the 1970s meant that libraries needed books in Vietnamese and Khmer (Cambodian) to support growing refugee communities. Similarly, upheavals in Iran in the 1980s led to increased demand for books in Persian. Norwegian, Latvian and Lithuanian, the languages of waves of post-war immigrants in the 1940s and 1950s, were gradually withdrawn as demand decreased. By the early 1990s, the collections included Hindi, Indonesian, Tamil and Thai, as people from these language groups arrived in Australia for study or work. We often hear from local libraries that suddenly have a new community in town because the local abattoir or factory has recruited people with skills from a certain country.

In 1974, a bulk loan meant a prepacked box of 30 books — 10 adult fiction titles, 10 adult non-fiction titles and 10 children’s books — sent out to a library on request. Collections were stored in boxes and distributed this way until the late 1980s, when the books were unpacked from their boxes and arranged on the shelves in the Library’s stacks. Now Library staff processing a loan request browse the full collection of a particular language that is available on the shelves and customise loans to what customers want, whether it be books by a particular author, or a subject or genre.

When the service started, the Library had funding to purchase around 2300 books in 16 languages. Annual reports during the first few years regularly mentioned ‘strong demand’ and ‘the need for more funding’ to purchase collections. Usage grew steadily and there were often waiting lists for particular languages. It could be hard to source some books, and staff kept track of books requested in languages that we did not hold, which informed collection development. We also loaned books to the Department of Corrective Services, and although this paused at some point, loans in a range of languages to temporary remand inmates at Silverwater Correctional Complex were reinstated in 2022.

In 1984, the service was renamed the Community Language Lending Service in line with a recommendation from the Ethnic Affairs Commission, and in 1988 it became the Multicultural Service. Today the Multicultural Bulk Loan Service holds almost 70,000 items in 43 languages — adult fiction, non-fiction and children’s books — for public libraries to borrow. Books are purchased from specialist suppliers, including some imported from booksellers overseas, often in the country of origin. Wherever possible, we purchase translations of Australian books. For example, we have Eddie Jaku’s 2020 memoir The Happiest Man on Earth available in five languages. Adult fiction and children’s books are the most sought after, which underlines the general demand for recreational reading.

Adult non-fiction varies and includes everything from cookbooks to self-help, religion, history, biographies, science, health, politics and society. One borrower asked if we could purchase Prince Harry’s memoir Spare in Greek. We were able to oblige.

Top 10 loans by language, |

Demand for children’s and young adult books has grown significantly, particularly bilingual books. One Korean parent said that she borrows Korean books and her son borrows English books from the library but that she enjoyed reading Korean picture books with him when he was a child. He is growing up as an Australian, surrounded by Australian culture, and she wanted to give him an opportunity to experience Korean culture.

Korean picture books reinforced their emotional and cultural bond. And of course the Harry Potter books are available in quite a few languages.

Many public libraries now provide their own collections in languages spoken by a substantial number of readers in their community. But they will often supplement these with books from the Library collections. This is particularly true for metropolitan Sydney, given the diverse population mix. Blacktown City Libraries have their own collections in 30 languages, but with over 165 language groups in their area, they rely on the Multicultural Bulk Loan Service to support those languages they can’t.

Wagga Wagga City Library is another unique case. A regional settlement area for refugees for over 20 years, Wagga Wagga now has over 98 community language groups and has drawn on the Library’s collections to support them. In 2022–23, Wagga Wagga borrowed books in 20 languages, including Italian, German, Chinese, Persian as well as books for an emerging Tibetan community. Staff highlight the delight families experience in being able to access picture books and junior fiction in their own language.

New languages are always being introduced. The Indian community is now the second-largest migrant group in Australia. In 2022, Telugu became the State Library’s seventh Indian-language collection, its development supported by the Telugu community. Some users have reported that reading books from the collection made them feel nostalgic for home. One reader, Pidaparthy Karthikeya Sharma, said, ‘I love Blacktown Library as it has multicultural books and especially Telugu books, which make me feel like it’s my home. It helps me to learn my mother tongue.’

In 2011, members of the Nepalese community approached the Library about setting up a collection. Our Nepalese collection, the first in Australia, was officially launched in 2014. And in 2023 we launched the first Tibetan collection in Australia, a collaboration with the Tibetan community and Northern Beaches Libraries in Sydney. Dee Why Library now hosts much of the collection to support one of the largest Tibetan communities in Australia.

Languages removed |

We constantly audit collections to ensure they meet the needs of the changing NSW community. Collections are set up or withdrawn based on community demand. The availability of books in a particular language, and reliable suppliers, are also important to ensure a collection is sustainable. Knowing what our culturally and linguistically diverse clients need is fundamental, so we collect data from public library staff, directly from communities and through government reports.

A few years back, the Ukrainian collection was marked for review because usage was low. Fortunately, this review was not enacted because since then the war in Ukraine has meant demand for this collection has skyrocketed. We have purchased additional books so are able to supply requests from libraries all over the state where those fleeing the war have been taken in.

The service is managed by a dedicated team, some with their own migrant experiences. Recently retired multicultural consultant Oriana Acevedo, who was born in Chile, started at the State Library in 1998 and her impact was immediate. She overhauled the collections, removing old and out of date books, and set about buying new books every year. She prioritised promoting the service, which saw a big increase in loans. In the 1990s, records for the books were added to the Library catalogue, replacing the manual card catalogue, but languages using characters, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Arabic-based script and Cyrillic text, were transliterated, which people couldn’t really read. During Oriana’s time books began to be catalogued with the title and author fields in the vernacular script so people can search in their own language. She also drove the creation of the dedicated Multicultural Unit in 2011, which saw turnaround time for loans improve from up to a month, to dispatch within one to two days.

Current service coordinator Joanna Goh, originally from Singapore, says, ‘I know firsthand how difficult it can be to assimilate to living in a new country. While having English as my first language helped me navigate the administrative hurdles, it did not fully remove the sense of homesickness and isolation of being apart from family, friends and a culture I grew up in. For migrants who do not have a good grasp of the English language, the transition can be many times harder. Our bulk loan service aims to provide the connection to the migrant community with their roots and the preservation of their language and culture.’

Collections are at the core of the work of libraries, which are some of the only spaces in society where people can go for free. Everyone should have access to information and culture that meets their needs, regardless of their background. It is powerful for people to be able to see themselves in such spaces and stories, and it is at the heart of giving a sense of belonging. We have been committed to making this possible since 1974.

Abby Dawson is a Specialist Services Librarian in the Public Library Services branch and managed the Library’s Multicultural Bulk Loan Service for nine years.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2024.