In October 1973 Alan Ninnes took on one of the most thankless jobs in South Australia. As coordinator of the Religious Education Project Team, he was given the task of creating a new religious education curriculum for public schools.

The new courses needed to embody modern educational principles, but also satisfy the demands of the South Australian Christian churches. Other groups, including political parties, a teachers’ union, parents’ organisations, and a particularly active humanist organisation would all become embroiled in a public controversy over religious education in the state. Meeting the expectations of these competing groups was a tall order for Ninnes and his team.

Finding Ninnes’ story was one of the most fascinating, and unexpected, parts of my fellowship research at the Library, which compares how religious education developed across the settler colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

As it turns out, Ninnes’ struggle was not unique. It’s one of many examples from the 1960s and 70s of how educators in all three countries struggled to find a place for religion in the public schools of increasingly pluralist societies.

This became clear to me as I read through the Library’s resources on this topic including the minutes of the Methodist Church (SA Branch), copies of the South Australian Teachers Journal, several important curricular documents and government reports, and the Education Gazette of South Australia.

Religious instruction got its start in South Australia in 1940 when, after a protracted lobbying campaign by Christian groups, a law was passed allowing a half-hour lesson each week. Students were divided up by denomination, and local clergy provided instruction. Parents could opt out their children if they chose.

Complaints about this system soon emerged. Not enough clergy were available to provide instructors for all schools, instructors rarely had any professional training as educators, and no standard curriculum existed. The system remained in place until 1968, when the Methodist Church of South Australia formally withdrew, essentially guaranteeing that the system collapsed.

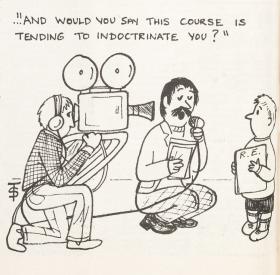

In 1972 the Minister of Education, Hugh Hudson, convened a committee (known as the Steinle Committee) to discuss the future of religious education. The committee’s report affirmed that religious education had a place in South Australian schools and could be conducted ‘on sound educational principles … without attempting to lead students to accept a particular viewpoint’. In other words, you could offer students an education in religion that avoided the problem of indoctrination. Exactly how this would be done, though, the committee left up to the Religious Education Project Team.

Ninnes and his team began their work with months of study. They read with interest the justification of religious education by American educator Philip Phenix. Ninnes travelled to Tasmania, which was undergoing a similar re-evaluation (by the early 1980s every Australian state would do the same). The international dimension of the project team’s work would culminate two years later when, in 1976, Ninnes travelled to the United States, Canada, and Great Britain to observe and research religious education programs.

In the mid-1970s, as a result of this research, the Religious Education Project Team produced a series of curricular documents with a new approach to religious education for South Australian schools. The program focused on ‘depth issues’, topics relating to self-understanding, identity and purpose. Students would be presented with questions on some of life’s most important questions, which they would have an opportunity to answer for themselves.

The new program also provided information about world religions — including Christian, non-Christian, and non-religious beliefs — encouraging ‘a greater tolerance for the beliefs of others’. According to the project team, the course would not indoctrinate because ‘it does not give preferential or derogatory treatment to religion in general or to any single religion’.

As the team deliberated and produced its first experimental curricula, a ferocious public controversy broke out in the South Australia. Opponents of the new curriculum, led by the organisation Keep Our State Schools Secular (KOSSS), believed it masked a preference for Christianity. KOSSS argued that ‘the curriculum is biased heavily in favour of religious belief and offers no account of alternative philosophies’ and suggested that religious education was simply not appropriate for young children enrolled in public schools.

By 1975 Ninnes and the team were on the defensive. Over about a year, they met with more than 150 parent and teacher groups to promote religious education and assuage concerns over their new curriculum. Their central claim was that the new program was ‘soundly educational’ and ‘an objective study’ of an important dimension of human life that should be part of public education.

KOSSS found this line of thinking totally unconvincing. In the hands of a zealous teacher, the group claimed, the new course would surely lead to some form of indoctrination. Though KOSSS was a relatively small organisation, it managed to generate a significant amount of negative publicity for the plan.

Over the next two years, the new South Australian religious education program was subjected to a rigorous review, which found no evidence that it would indoctrinate students. But the damage had already been done.

The course development was delayed during the review, and the public became wary. Though judged to be educationally sound, the new program failed to attract enough ardent supporters. It was criticised by some Christian churches, notably the Lutheran Church of South Australia. Schools were given the option of choosing whether to implement religious education, and by the end of the 1970s fewer and fewer schools were participating.

The story of the Religious Education Project Team in South Australia is a compelling episode in the long-running drama of religion in public education. Though their work fell far short of their own expectations for the new religious education curriculum, Alan Ninnes and the team tackled pivotal questions that are still being asked today: What role should religion have in public schools? Can you teach students about religion without indoctrinating them? And if religious education is not offered, do the public schools implicitly endorse non-religious philosophies?

These vital questions have no definitive answers, but reveal a great deal about the societies that ask them.

Dr Stephen Jackson is Associate Professor of History at the University of Sioux Falls, United States, and the Library’s 2019 Australian Religious History Fellow.