It has been a revelation to explore collections in the State Library that deal – directly or indirectly – with the lives of people with disability.

We often use the terms ‘invisible’ and ‘marginalised’ to complain about the absence of these stories in mainstream history, but I’ve found many intriguing primary sources, and some detailed and eloquent published accounts.

When historians write about people with disability, they often focus on one organisation and, therefore, on a particular group of people. Although these histories can be compelling and thoroughly researched, they don’t always link into the wider story of disability in our society.

I have been looking for the social history, the ‘history from below’ – trying to recover experiences of people with disability rather than institutional histories and overviews of Australian legislation and policy. This is always a challenge, as most of the records are left by the people in charge.

But the Library’s collection offers some surprising gems. Most of the relevant materials have not been left directly by people with disability, but by the organisations that cared for or represented them – if read ‘against the grain’, however, they reveal much about the lived experience of people with disability and show us lines of enquiry for further research.

Australia’s first charity was the Sydney Benevolent Asylum, established in 1813. Its early aims were to ‘to relieve the Poor, the Distressed, the Aged, the Infirm’, and it was usually the first port of call for those in hardship. Some – possibly many – of the destitute and needy people referred to the asylum were people with disability; sometimes whole families were thrown into chaos through the disability of one or more members and found themselves in the asylum.

This long-running organisation (now the Benevolent Society) has placed an invaluable collection of historical records, from 1813 to 1996, in the Library, and voluntary archivists associated with the modern organisation are very helpful in navigating the early records.

There are many entries for people with ‘weak intellect’, people listed as ‘imbeciles’ who could ‘give no particulars’, those who were ‘deaf and dumb’ or had ‘weak eyes’. Although the records do not give us the full story of these people’s lives, they point to the impact of disability on individuals and families during this time, and are something of a road map for the slowly increasing range of institutions in the nineteenth century. The asylum referred many people to places such as the ‘Deaf and Dumb Institution’, the ‘Blind Asylum’, or the ‘Imbeciles Asylum’ in Newcastle, which means we can further trace their pathways.

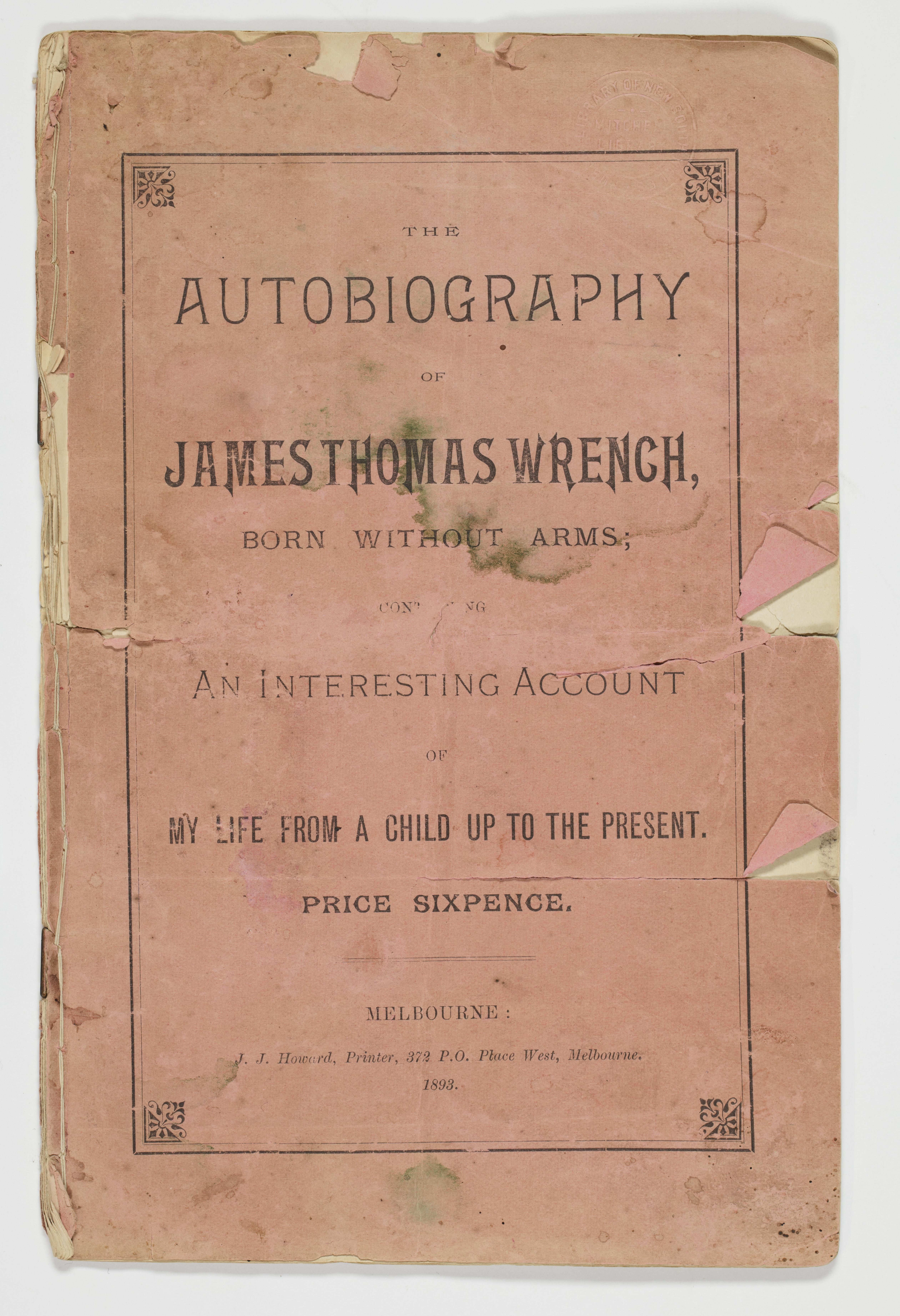

Occasionally, we are fortunate to have a personal account from a person with disability. An article in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser on 30 July 1898 referred to an unusual visitor to the newspaper office: ‘one James Thomas Wrench, 2ft. 9in. high, born at Sofala in 1868 without arms, and with one leg very short and without a knee joint, and minus one of his toes. He is being shown in Sydney as a freak under the name of “General Peden”, and sat down and wrote his autograph with his toes as easily as an ordinary person could do it with his hands.’

The article gives us a brief insight into the social view of people with physical disabilities during the late nineteenth century, and the ‘freak’ industry which grew around them. But, in this case, we also have Wrench’s own perspective, in a small collection his family later placed in the Library. It includes a short ‘Autobiography’, self-published in 1893, describing his family life, education and artistic work. Wrench’s story is an engaging early account of the importance of physical access to places such as school buildings, and of the crucial influence of a supportive family and enlightened teachers.

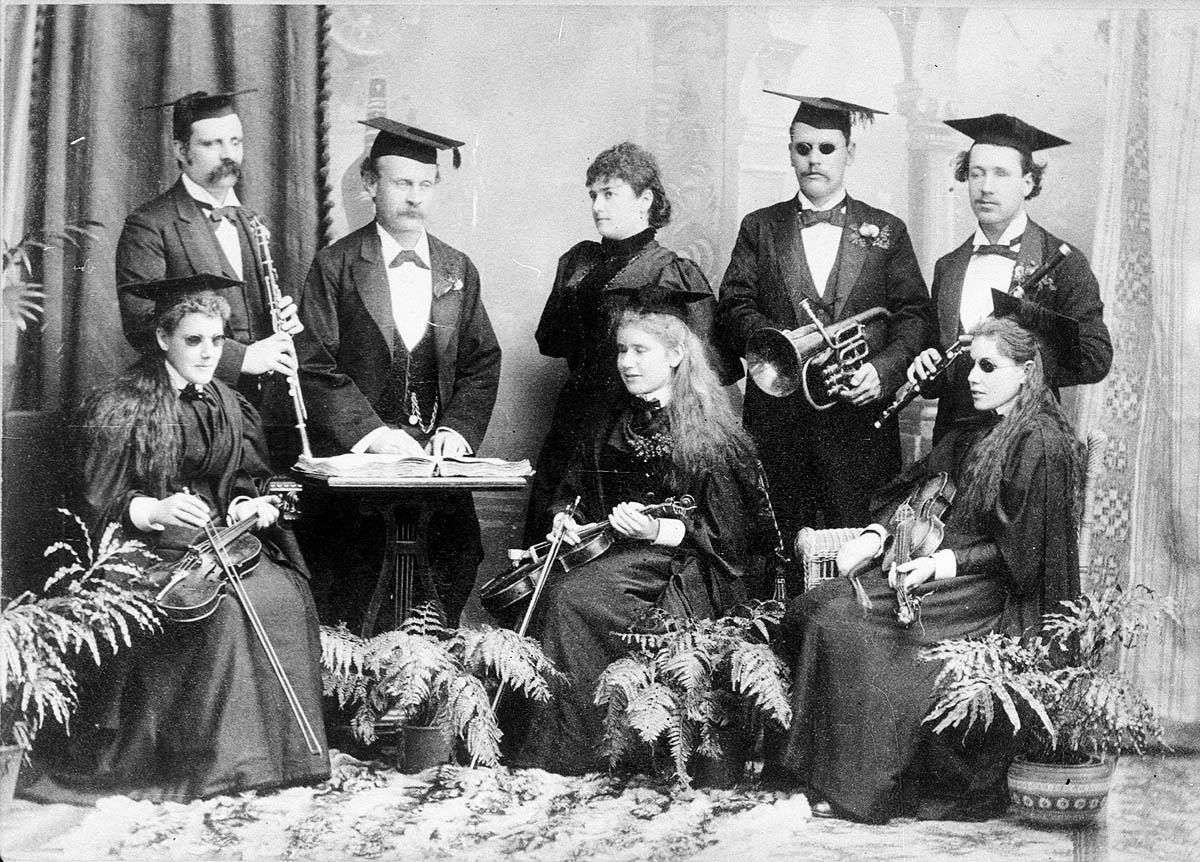

As well as individual experiences, evidence of collective action by people with disability also caught my attention. During the 1920s and 30s, there was political unrest and radical activity within many minority groups in Australia (reflecting unrest in wider society) – women and Aboriginal organisations, for example, were agitating for greater social participation and citizenship rights, and so were some groups of people with disability.

Institutional records often provide detailed accounts of the external challenges they face. The records of the Royal Blind Society, for example, include voluminous files from their Industrial Blind Institution, which was challenged on some of its practices – such as its compulsory ‘boarding-in’ rule and lack of representation for blind people on its board of management – by the Association for the Advancement of the Blind (later Blind Citizens NSW). These records help us to understand the experiences of the blind people who were part of the institution.

In 1929 there was an acrimonious breakaway from the Adult Deaf and Dumb Society of NSW when a large part of the Sydney Deaf community felt they were not represented in the society’s governance. A new rival organisation was formed: the NSW Association of Deaf and Dumb Citizens, which published The Deaf Advocate magazine between 1930 and 1937. The Library holds one of the few remaining collections of this magazine – a rich resource on the political issues and everyday lives of deaf people in Sydney at the time.

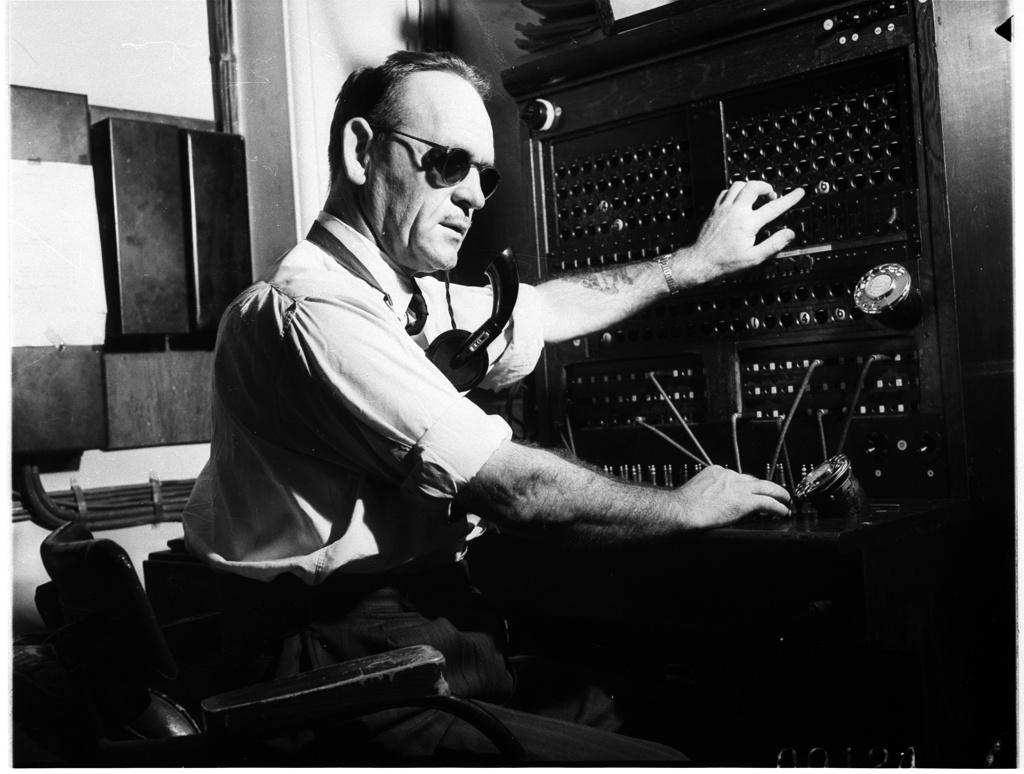

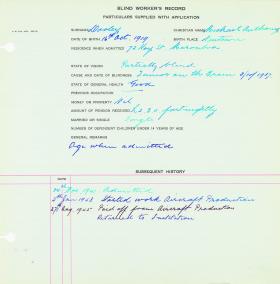

The opening up of women’s employment options during the Second World War is a familiar story, but it is less well known that the same thing happened for many groups of people with disability. The Royal Blind Society’s collection includes ‘Blind Worker’s Records’, which detail workers’ movements in and out of the Industrial Blind Institution, recording any outside work they found. These records show that many blind people found work in armaments and aircraft factories in the early 1940s.

Many deaf people had a similar experience, as noted in the Adult Deaf and Dumb Society of NSW’s annual report of 1941–42: ‘The present war has transformed the position with regard to employment of the deaf. Before the outbreak of the war large numbers were unemployed, but this year we cannot place our hands on one unemployed deaf and dumb person who is able to work. In every case those employed are receiving full award wages.’

We may have moved towards a more inclusive and accessible society, but institutions such as the Peat Island Centre (formerly Hospital) and the people who lived there are a rich and instructive part of our history. Peat Island, on the Hawkesbury River, was a residential centre for people with intellectual disability for 100 years between 1910 and 2010. In the late twentieth century, centres like this were the subject of heated debate about institutional care for people with disability, especially after the Richmond Report in 1983 (the Inquiry into Health Services for the Psychiatrically Ill and Developmentally Disabled).

As most large institutions such as Peat Island have closed, it is important that the experiences of those who lived there are not lost. We are fortunate that the research material for Laila Ellmoos’ excellent history of Peat Island has been placed in the Library, including interviews with many former residents. This collection gives insights into the everyday experiences of residents, staff, families and administrators, and contains artefacts such as magazines produced by the school on the island.

People with disability are not absent from our historical records. Their voices are often muffled by the dominance of institutional histories, but they are present if we search in the right places. These collections at the Library, along with records in other libraries and archives, show the kinds of stories that might inform a truly inclusive history of Australia. As historian Douglas Baynton has observed, ‘Disability is everywhere in history, once you begin looking for it … but conspicuously absent in the histories we write.’

Dr Breda Carty was the Library’s 2017 CH Currey Fellow. Her book Managing Their Own Affairs: The Australian Deaf Community During the 1920s and 1930s was published in 2018.