Penny Short was a trainee teacher at Macquarie University in 1973 when her untitled poem was published in the student paper Arena. An extract reads:

Warm bodies entwined in love

soft kisses are not enough

stroking your breasts

my knee slides up between your thighs

feels soft, slippery, throbbing cunt

When the Department of Education became aware of the poem, it declared her ‘medically unfit’ to teach primary school students and revoked her teaching scholarship.

In the same year that Penny’s poem was published, Jeremy Fisher was expelled from the university’s Robert Menzies College when, following a suicide attempt, gay liberation badges were found in his room. The college’s master, Alan Cole, told Jeremy he would only be allowed back into college if he agreed to repress his homosexuality. He refused.

Before the 1970s an openly gay life in Australia was inconceivable. Male homosexuality was outlawed, female homosexuality was either shrouded in silence or completely ignored, and same-sex attraction was considered a psychiatric illness. Any representation of gay love in mainstream media presented homosexuality as sick, criminal, and socially and morally reprehensible.

This all began to change 50 years ago, on 19 September 1970, when John Ware and Christabel Poll appeared in an article titled ‘Couples’ in the Australian presenting a positive image of gay life.

John and Christabel made history by publicly discussing their lives with their same-sex partners, and agreeing to be photographed and have their real names published. They were promoting a gay rights group they had recently started — Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP) — and called for same-sex attracted people to come out and join the fight for a fairer, more just society.

‘If every homosexual admits it, and talks freely,’ said John, ‘the public will eventually get rid of their misconceptions.’

CAMP was officially launched the following year, on 6 February 1971, at St John’s church hall in Balmain. At the meeting, John and Christabel were confirmed as co-presidents of the organisation, now considered one of the most influential groups of the gay rights movement in Australia. CAMP’s goal was to end discrimination, achieve equality before the law, take political action, and encourage people to come out.

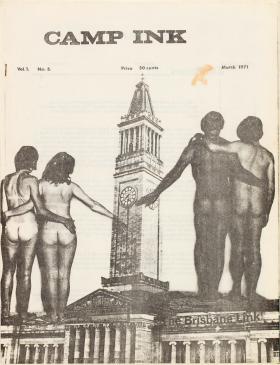

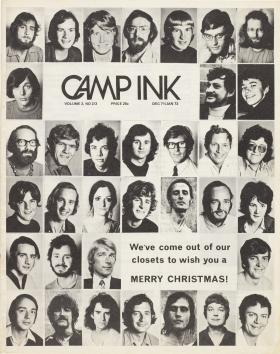

And come out they did. Following the launch of CAMP, branches sprang up around the country. The organization printed 500 copies of the first issue of its magazine CAMP Ink, and by the following year had more than 1500 members. Over the next decade the group was among those at the forefront of the charge for social, legal, educational and political reform.

CAMP organised the first demonstration for gay rights in Australia, protesting outside the Liberal Party’s Sydney headquarters on 6 October 1971, in support of Tom Hughes, a candidate who supported homosexual law reform.

A year and a half later, in April 1973, CAMP established the ‘Phone-A-Friend’ telephone service, which later became a counselling hotline and is still in operation today as Twenty10. More militant groups like Sydney Gay Liberation and the Radicalesbians were formed alongside the CAMP movement, and together they rallied for change.

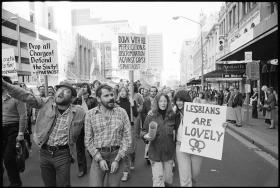

Towards the mid-70s, the gay rights movement picked up momentum as the unions joined forces with the gay community. When Penny Short lost her scholarship, students — and not just gay and lesbian students — were outraged. A demonstration of some 600 people gathered outside the Education Department’s headquarters, demanding reinstatement of her scholarship.

Students also mobilised when Jeremy Fisher was expelled, the Staff Association condemned Robert Menzies College, and the Builders Labourers Federation urged members to walk off the many construction sites on campus. The strike is remembered as the world’s first ‘pink ban’. However, Penny’s scholarship was never reinstated, and the college refused to offer Jeremy his room back without the condition that he renounce his homosexuality.

Tracing the milestones in the gay rights movement over this decade, the Coming Out in the 70s exhibition at the State Library of NSW offers insights into exactly what it took to achieve legal and social equality in Australia. For me, it’s an astonishing glimpse into what went on in Australia at this time.

I think of how French lesbian feminist author Monique Wittig describes a new form of writing as having the power of a war machine. ‘The goal and design is to pulverize the old forms and formal conventions,’ she writes. ‘It will sap and blast out the ground where it was planted. The old literary forms, which everybody was used to, will eventually appear to be outdated, inefficient, incapable of transformation’ (‘The Trojan Horse’, 1984). A campaign, I think, must work in a similar way — first there is a single spark, then the long process of change.

The 1970s was a decade full of firsts. In 1971 the definitive text of the gay rights movement, Australian activist Dennis Altman’s Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation, was published. Altman had witnessed the rise of gay and lesbian political activism in the US after the Stonewall riots of 1969 and, like CAMP, he called for personal change as well as social transformation.

The following year, on 31 October 1972, Peter de Waal and Peter Bonsall-Boone made history when they kissed on the ABC’s Chequerboard documentary. This was surely one of the most controversial moments in the history of Australian TV, as Bonsall-Boone lost his job as secretary of an Anglican church as a result of the appearance, sparking large protests.

This was also the year that Number 96 introduced Australia’s first openly gay soap character, Don Finlayson, played by Joe Hasham. Remarkably, the show’s creators wanted to steer clear of stereotyping the character, choosing instead to present him as an everyday guy who just happened to be gay.

Then came TV’s first lesbian kiss, on 11 February 1974, between Felicity (Helen Hemingway) and Vicki Stafford (Judy Nunn) on The Box. The first lesbian novel in Australia was published the following year, Kerryn Higgs’ All That False Instruction — the same year the first state in the country, South Australia, decriminalised the male act of homosexuality.

The first Sydney Mardi Gras parade, on 24 June 1978, began as a peaceful demonstration but a march through the streets that night turned brutal. At Kings Cross, police made 53 arrests under the Summary Offences Act which gave police broad powers.

The following Tuesday, the Sydney Morning Herald published the names of all those arrested. Some lost their jobs. Others were disowned by their families or lost their tenancy rights. Some committed suicide.

In response to the police brutality that night, and the subsequent arrests, the gay community mobilised. The ‘Drop the Charges’ campaign eventually led to the repeal of the Summary Offences Act in May 1979 and the creation of the new Public Assemblies Act, which meant people no longer had to apply for a permit to have a demonstration.

This set the stage for the next phase of change, with significant achievements in New South Wales including the legalisation of homosexuality in 1984, a removal of the ban on same-sex attracted men and women serving in the military in 1992, the implementation of legislation allowing same-sex couples to adopt in 2010, and the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2018.

These milestones, and the rest, are just some of the moments that marked the decades following the formation of CAMP. I wasn’t born in the 70s, but from this distance, it seems to me that the moment John Ware and Christabel Poll came out publicly, and encouraged others to do the same, everything started to change.

The 70s was full of action — rallies, marches, meetings, spontaneous actions or ‘zaps’ — but the force that drove the movement seems to be the simple, courageous act of coming out and saying ‘I’m gay.’ Whether through writing a poem, joining a group, wearing a badge, attending a rally or appearing in the media, many people in the 70s who were brave enough to name themselves in an intensely hostile world.

Robyn Kennedy is one of these people — from the first Mardi Gras to the bid for World Pride 2023 (which she led) Robyn is a pioneer activist for social justice. As the youngest member of CAMP in 1973, she quickly moved up the ranks and was a key player in the fight for gay liberation.

As part of her work at the time, Robyn was one of many activists involved in ‘public education’. They would visit schools and universities, and go on the radio in an effort to try to break down stereotypes about what it was to be gay.

When I speak to her over the phone, she describes the toll this would take. ‘I found it pretty hard doing that kind of work,’ Robyn says. ‘Every time I’d have to go and do it I’d get stomach cramps because it was so personal. I didn’t like it at all. I did it because it was important to demystify and show we weren’t sick, we weren’t criminals.’

For Robyn, the Coming Out in the 70s exhibition is about the importance of history, of recognising the enormous personal sacrifices made by those who were among the first to stand up and demand change. ‘It’s not about a trip down nostalgia lane, it’s recognising that individuals can achieve massive social change if they’re committed enough and if they work together.’

by ABC. Peter De Waal Papers. Reproduced courtesy Gabrielle Antolovich and the Australian Broadcasting

Corporation – Library Sales © 1972 ABC

For her, it’s also a chance to take stock, to recalibrate our understanding of where we are at now, and how vital it is to continue working for equality, visibility. ‘It takes 40 years to make things go away,’ Robyn said, ‘and then it can be so easily lost — what has been achieved at great personal cost. You can’t let them slip away.’

What strikes me about CAMP, and about the 70s as an era of monumental change in Australian society and culture, is that the fight for liberation was so incredibly personal. It was about each person coming out, whatever that meant or took for them — and at the same time it was about coming together as a community.

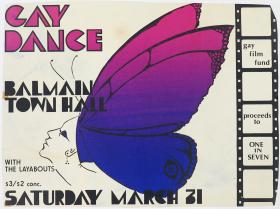

There were the Gay Lib Dances, the National Homosexual Conferences, the Feminist Bookshop, Gay Radio, and the CAMP club rooms in Glebe where you could just pop in for a coffee, a chat, or to ‘raise your consciousness’. And, of course, there were the marches. ‘Demonstrations were our internet,’ Robyn tells me. ‘It was the only way to convey in a real and public way what was wrong with society and what we wanted changed. Everything we did we did together.’

The call of CAMP, as an organisation, was for social and political change — but its primary call was for same-sex attracted people to come out. The idea was that the more people come out as gay, the more okay it will be in society to be gay.

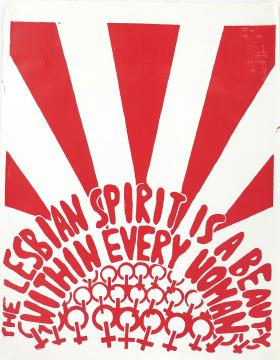

This call is not lost on me, 50 years down the track. Browsing through issues of CAMP Ink, and visiting the exhibition, I’m as moved to see ‘Homosexuals Come Out’ and ‘Gay is Good’ printed on a page, to see ‘Lesbians Are Everywhere’ stamped on a badge, as I think I would have been if I was there at the time.

It makes me think about the significance of visibility — of publishing and printing and living a visible, positive gay life. Words are sometimes where it starts, and it matters that they said those words, that they printed them, that they were proud. It mattered then, of course. And it still matters to us, now.

Ashleigh Synnott has published stories, poems and essays in journals such as Meanjin, Overland, Southerly and Antipodes. Her first book, Monster, will be released by Puncher and Wattmann next year. She lives and works in Sydney, on Gadigal land.

Coming Out in the 70s is a free exhibition in the State Library’s galleries until 16 May 2021.

This story appears in Openbook Summer 2020.