Off to the diggings: the gold rush

Successfully drumming up enthusiasm for gold in the west, Hargraves set about publicising it via articles in the Sydney Morning Herald and holding court at Bathurst, lecturing and explaining techniques for gold mining.

Colonial geologist Samuel Stutchbury travelled to Ophir to confirm gold finds for the government. In his report to Governor FitzRoy on 19 May he wrote:

'gold has been obtained in considerable quantity…the number of persons engaged at work and about the diggings…cannot be less than 400 and of all classes.'

- Governor FitzRoy despatches, May 1851.

He apologised for his report being written in pencil, '…as there is no ink yet in this city of Ophir.'

The government declared a gold discovery on May 22, 1851.

"gold has been obtained in considerable quantity…the number of persons engaged at work and about the diggings…cannot be less than 400 and of all classes."

Governor FitzRoy despatches, May 1851.

The government feared that the entire labouring class would abandon their duties in Sydney as clerks, labourers and servants failed to appear for work as thousands rushed west for the newly named "Ophir" gold field.

There was a concern that shepherds, drovers and farmers would abandon the developing agricultural industries that had been prospering the young colony. Governor FitzRoy wrote to Earl Grey on 29 May reporting that:

'thousands of people of every class are proceeding to the locality, - tradesmen and mechanics deserting certain and lucrative employment for the chance of success in digging for gold, - so that the population of Sydney has visibly diminished.'

- Governor FitzRoy despatches, May 1851.

Pastoralist James Macarthur suggested that martial law be introduced to prevent complete chaos. However the news spread of Hargraves' discovery and it was impossible for the government to stop the flow of people westwards. The one conversation around Sydney was, 'Have you been?' or 'Have your servants run yet?'

Sydney shopkeepers, canny in their ability to turn a profit and create consumer demand, began to fill their windows with all manner of miner’s wares. Blue and red serge shirts, 'real gold-digging gloves', mining boots, blankets and other camping goods became staple items. The newspapers were filled with advertisements for items to take to the gold fields.

On the roads to the diggings, all classes of people travelled with their belongings. There was an atmosphere of excitement and impending wealth. Eye-witness, Godfrey Charles Mundy, a soldier and writer saw:

"..sixty drays and carts, heavily laden, proceeding westward with tents, rockers, flour, tea, sugar, mining tools, etc. each accompanied by from four to eight men, half of whom bore fire-arms. Some looked eager and impatient, some half-ashamed of their errant, others sad and thoughtful, all resolved."

By the end of May 1851, hundreds of diggers had arrived in the Ophir region and had begun their search for gold.

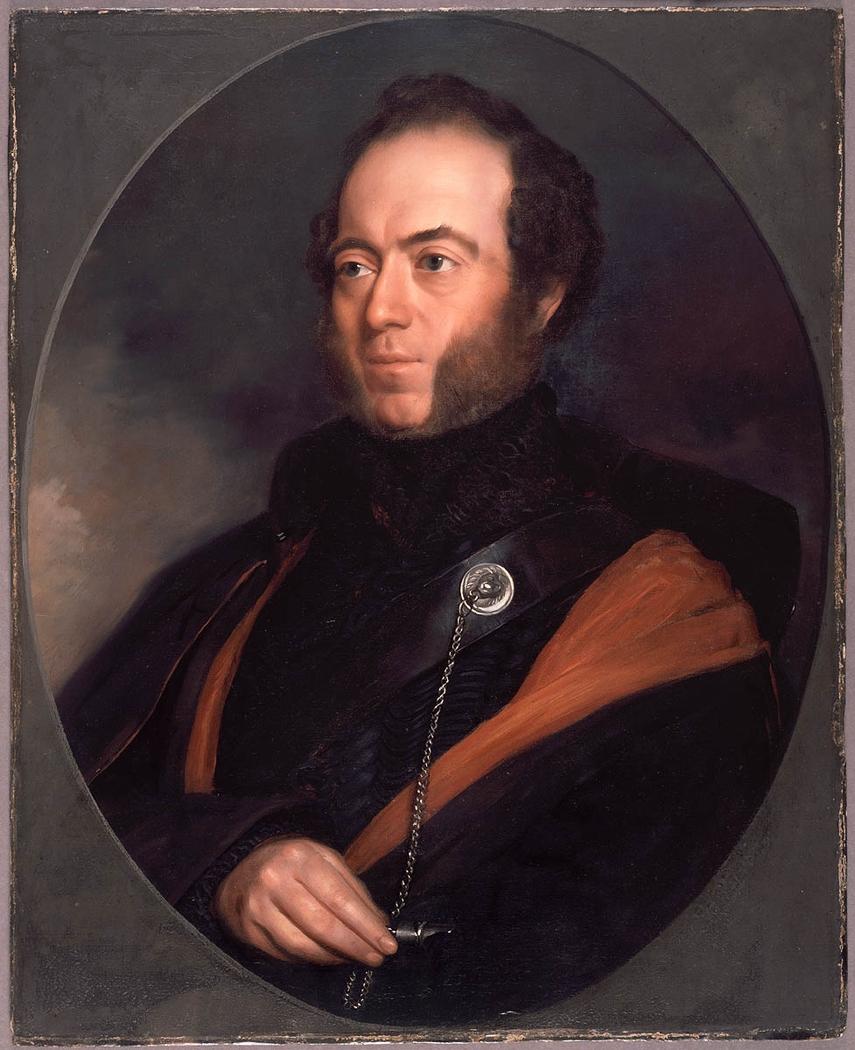

Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell

Surveyor-General of New South Wales from 1828-1855, Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell undertook four expeditions into the interior of Australia between 1831 and 1846. He published several accounts of his explorations. The State Library holds his collection of papers, including his diaries, journals of his expeditions and his field books.

Mitchell was one of many who travelled west during the winter of 1851 to visit the Ophir gold diggings along with his son, Roderick, and the government geologist, Samuel Stutchbury. Governor FitzRoy requested Mitchell to 'survey the extent and productiveness of the goldfield reported to have been discovered in the County of Bathurst'.

Mitchell surveyed the area around Summerhill Creek and the ‘town’ of Ophir.

He describes the scene when he arrives:

"I counted about 200 men at work, besides what were also in sight higher up and lower down the river, on the opposite bank, high above the river were numerous tents, as well as on the left bank of the river – and a bark home with placards about booking for mail, and about all kinds of stores sold there stood on river bank close to the diggers."

Gold Chest belonging to Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell

While on his journey to Ophir in 1851, Sir Thomas Mitchell collected a number of gold samples, stored in a wooden chest.

There are 48 specimens, mostly quartz, varying in colour, shape and texture. Most have light concentrations of gold, a few have heavy concentrations. The chest also contains specimens of gold dust. All the samples were taken from gold diggings in New South Wales in 1851.

Canvas Towns

The canvas town of Ophir had materialised overnight as tents were set up along the hillsides. It was winter when the diggers first began to move into areas north of Bathurst along the Turon River. There were reports of heavy frost and rain which quickly turned the diggings to mud. Diggers then moved on through out New South Wales as new goldfields were being opened up.

Gold diggers moved from Sofala, Gulgong, Hill End and Bathurst in the Central West of NSW south to new diggings at Lambing Flat (Young), Braidwood, Tilba Tilba and Kiandra in the Snowy Mountains. The short-lived gold rush at Kiandra was waylaid with heavy snowfalls in 1860.

On the diggings there were no class barriers. Physical strength, health and determination were attributes that would bring the most reward. The only social distinction was between the old chums and the new chums.

These adventurous diggers were some of the first to ski in the area, strapping wooden palings to their feet.

The old chums were native born, or had lived in the colony for a long time, possibly ex-convicts. They considered themselves superior to the new arrivals and enjoyed the prestige of being experienced diggers. New chums tried valiantly to keep up, working diligently on their appearance so they looked like old chums; wearing dirty, battered cabbage-tree hats, growing their beards and moustaches long and ensuring they were proficient in colonial swearing habits.

Initially alcohol was prohibited on the diggings and sly grog tents appeared along the gold fields. Owners caught selling illegally were given a 50 pound fine and a possible gaol term and had their stock confiscated. However, the demand on the goldfields was too tempting and the sly grog tents proliferated along the diggings. Eventually the government gave up its prohibition and granted licenses. Spirits were allowed to be sold by public houses which had officially paid the license fee to sell liquor. Pubs on or near the goldfields were successful as long as diggers were striking successful loads of gold in the area. After a few weeks steady business, the pub would have recouped the expensive license fee of around 100 pounds per year.

The one government measure to prevent chaos on the gold fields and a total exodus from the cities was to institute the licensing system for miners.

Accounts

Each goldfield had a butcher’s shop and many grog shops (sometimes canvas tents). A digger’s diet consisted of steak or mutton fried in fat for every meal with plenty of bread. Tea was the standard drink. A high-calorie intake was required for long hours of physical labour. Watered-down milk for coffee and fresh bread was delivered to miners each morning – with the price considerably more for the new chums recently arrived.

Ellen Clacy visited Australia with her brother in 1852. Her lively account of her travels was published on her return to London in 1853. Visiting Australia at the height of the rush, her observations on the diggings and the diggers provide a fascinating social history. She describes the food available on the diggings and the high costs of basic provisions.

Staples such as flour, tea, sugar and other foodstuffs had increased greatly in cost.

William Anderson Cawthorn

William Anderson Cawthorne was born in London in 1825. He was an artist, author, and schoolmaster. Immigrating to South Australia with his parents in 1841, he opened a school in Currie Street, Adelaide and in 1852 became headmaster of Pulteney Grammar School. He taught until 1862 when he became founder and secretary of the National Building Society. He is particularly remembered for his strong interest in and knowledge of Indigenous Australians and published a number of works on their history, traditions and customs.

As a young man, Cawthorne recorded his observations on the gold rush and how Adelaide had been affected by the rush to Victoria. He notes that 'Everything is horribly dear in Adelaide' and of the sharp reduction in population due to the rush to the goldfields. On December 12 he wrote,

'Adelaide is in an awful state everybody leaving it - for the gold diggings at Mt Alexander - Ballarat - Men there are getting fortunes - in a few weeks - men… going away - leaving their wives & children behind - the Cads - work of all kinds is stopped'

Despite his criticism of men leaving to go in search of gold, Cawthorne too travelled to the Victorian goldfields via Melbourne to try his hand. However after only a few weeks, he returned home to Adelaide, unwell and penniless.

Andrew Clunie

Englishman Andrew Clunie wrote diligently to his mother and sister back home in London between 1856 and 1865. His nineteen letters tell of the experiences of one immigrant who intended to go gold mining, but diversified into other businesses such as shoemaking and operating a ferry to supplement his income from gold digging. All these ventures met with little success, likewise his search for an appropriate wife.

'there is nothing suitable here - such a rowdy lot of Women, I would not get married in this country for fear I should never get out of it.'

In his last letter, dated 1864, he announces he has booked his passage home.