Tucked away just inside North Head, the station has a spectacular view of coastal Sydney — from the CBD towers in the south, to the dense bushland of Middle Head and unfolding suburbia. Ferries are still sailing to and from the city, though they’re mostly empty. Many workers have begun to work from home, while others have lost their jobs. We’re all trying to adapt to self-isolation.

Sabrina and I are still in that early rush of adrenalin and adjustment. On our last day at the Library, we stuffed several backpacks full of sound-recording equipment and mics in case we wouldn’t be able to step outside our homes. Our intention is to document our self-isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic, and to research and record a podcast series about the last great influenza pandemic that hit Australia in early 1919.

As we walk down the road towards Quarantine Beach (keeping the requisite distance apart), it feels great to be outdoors in the fresh air, to breathe in the eucalypts and to hear water lapping on the sand — a haven of calm and remoteness, despite being so close to metropolitan Sydney.

It’s just a day after the NSW government issued two public health orders: the COVID-19 Self-Isolation Order, requiring that a person diagnosed with the disease must self-isolate; and the COVID-19 Gatherings Order, directing the closure of all places of public gathering including ‘food courts, spas, beauty salons, massage parlours, tattoo parlours, betting agencies, sex services premises, strip clubs, outdoor play areas, public swimming pools, caravan parks, libraries, museums, galleries, community facilities, hairdressers, gyms’, and the extraordinary curtailing of wedding and funeral attendance. The title struck us as peculiarly dystopian: The Gatherings Order. It seemed like a good name for a podcast.

We discuss how we feel about the closures as we walk through the bush to look at some engravings on the sandstone rocks that overhang the beaches and inlets.

The Quarantine Station is a good place to begin a conversation about disease, pandemics, self-isolation and super-spreaders. It was here in 1835 that the first quarantined ship, the Canton, was moored after a smallpox outbreak on board.

An account in the Library’s collection, written by 16-year-old John Dawson, tells of travelling with family members to Australia on the Canton. His little sisters contracted smallpox and the immigrant family spent their first days in the country camping at North Head, quarantined away from the town.

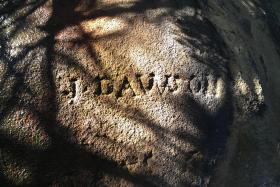

While he was there, John engraved his name into the soft sandstone rock: ‘[J]. Dawson landed here to perform Quarantine’. The first European to leave his markings at this spot, he unwittingly started a tradition. Wave after wave of quarantined passengers and crew have inscribed their names — or elaboratively carved and painted their ship’s and crew’s names — into the rocks all over North Head.

Delving into the history of quarantine and disease outbreaks over the past century, we can’t help but compare those histories to the present chaos unfolding in the news. As infections are being reported aboard the Ruby Princess and Diamond Princess, we are researching the cross-border transmission of contagious diseases in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, often via ships.

The 1918–19 ‘Spanish flu’, or pneumonic influenza, was the last great global pandemic, and the social responses to that virus resemble contemporary responses to Covid-19. Just over a century after the influenza pandemic arrived in Sydney in January 1919, Australia’s first Covid-19 patients were identified, in late January 2020. Both viruses attack the respiratory system, with symptoms including fever, coughing, and shortness of breath. Both are highly contagious, the only way to contain them being isolation and quarantine. No vaccine was found to protect against the 1918–19 virus.

The 2020 NSW government’s orders mirrored the ones issued in late January 1919. When the Library closed in 1919 for some 10 weeks, it’s unlikely that many staff were able to work from home. But in 2020, we have all adapted and have been delivering a variety of services online.

Working remotely, Sabrina and I plan, research and write podcast scripts, seek out experts and interview them using online platforms. Sabrina records, edits and produces the episodes, and I narrate them.

Our subject experts are generous and in demand, fielding many media interviews about the nature of pandemics. Among them are former Library fellow Dr Peter Hobbins — who shared fascinating medical history insights in our previous series, The Burial Files — and Dr Kirsty Short, senior lecturer at the University of Queensland, an expert in infection, immunity and pandemic preparedness.

Other experts help us understand how scientists, politicians, the economy and NSW society responded to the influenza pandemic. We examine how Aboriginal communities in NSW were particularly hard hit by the 1919 influenza pandemic, and are delighted to have Professor John Maynard from the University of Newcastle provide the broader context for Aboriginal people living in NSW during those early decades of the twentieth century.

In between, we reflect on our day-to-day experiences in lockdown, and how our community and our state are dealing with restrictions and a transformed way of living. We ask how our responses to Covid-19 compare to those of our 1919 forebears? Have we learnt anything new in how to respond to pandemics?

The Library’s collections reveal much about the 1918–19 influenza pandemic, beginning with the first Australians to suffer from the virus in mid-1918, and those who treated them. Vivid descriptions of the symptoms can be found in World War I diaries, along with the soldiers’ colloquial name for it: ‘the dog’s disease’. This is how Australian nurse Anne Donnell, who treated Australian patients in an English hospital, described it:

It’s a terrible flu. The worst I have come in contact with. It starts with an ordinary cold — and if neglected some turn into a general aching with severe pains in the small of the back and at the back of the head — also great tenderness over the balls of the eyes … Then almost without warning an acute Pneumonia sets in — which makes it hard to combat. We lost one of the dearest boys that way & so suddenly, Sargent Bradford from Murray Bridge.

Diary quotes, voiced by actors in remote recording studios, are woven through the episodes. Despite the distance, our actors love interpreting these voices from a century ago and are quick to recognise the many parallels between today and 1919, such as the spread of Covid-19 on ships and the frustrations with quarantine.

As the number of cases begin to rise again in July and Melburnians go into stage 4 lockdown, Australia has still managed to keep the death rate low, compared to many other countries. The influenza pandemic of 1918–19 took around 15,000 lives across the country.

Some of those victims lie amid wildflowers, grass trees and banksias in the third quarantine cemetery at the crest of a hill at North Head. We enter the open gate and see Annie Egan’s grave just inside, a large marble cross marking her place of rest. Sister Egan had been assigned to her first nursing post at the Quarantine Station after completing her training. Tragically, like many of her fellow medical professionals, she contracted the virus and died at North Head in December 1918 at the age of 27. At her burial, wreaths of wildflowers were placed on her grave and full military honours performed. Inscribed on her headstone: ‘Her life was sacrificed to duty.’

Elise Edmonds, Senior Curator, Research & Discovery

The new podcast series, The Gatherings Order, is available from 5 September.

Pandemic! — a display of collection items from the influenza pandemic and new acquisitions documenting the impact of Covid-19 — is on Lower Ground 1 from 5 September 2020 as part of NSW History Week.