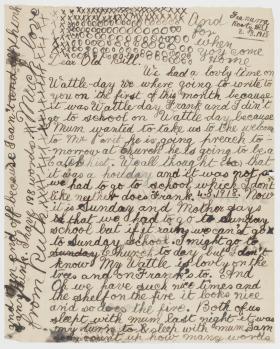

Is his spelling not dreadful — he thinks you like it like that as you know he has written it without help.

— Annie Burrowes

Six-year-old Frank and his big sister Ruth wrote regularly to their father, Sergeant Arthur (Bill) Burrowes, who served in the trenches of France during the First World War. The family lived at Rooty Hill — then a rural district — with a menagerie of cows, chickens and goats, and a puppy called Bing.

Frank and Ruth wrote to their ‘dear old Dad’, telling him their news from home: getting a new puppy, having a day off school, how they took turns sleeping with mum. As they carried on, despite the absence of their father, love was sent across the oceans in the form of hugs and kisses scrawled all over the paper. Bill Burrowes tied their letters into a bundle and carried them throughout his war service, until they returned home safely with him at the end of the war.

The generation born between 1900 and the outbreak of war in 1914 would live through two world wars. As children, they farewelled fathers, uncles and older brothers departing on troopships for the Middle East and Europe. As adults, many enlisted in the Second World War and, like the previous generation, travelled to distant locations where they continued the tradition of writing home to family.

The children of the First World War were brought up to be loyal members of the British Empire. In maps on classroom walls, much of the world was covered in red to indicate the breadth of the empire; children learned the history of British kings and queens and the noble reasons that Britain was compelled to confront the aggressor, Germany.

Publications for children during the war included ‘boys’ own’ adventure stories depicting brave young men enlisting and fighting for the empire, feats of daring in magazines such as Chums, and the popular Billabong series of books by Mary Grant Bruce. First published in 1915, From Billabong to London follows three children who travel ‘home’ to England where the boys, Wally and Jim, enlist in the British army:

The long voyage, with its comparative peace, was behind them: ahead was only war, and all that it might mean to the boys. The whole world suddenly centred round the boys. London was nothing; England, nothing, except for what it stood for; the heart of Empire. And the Empire had called the boys.

Jim had desperately wanted to join up:

Of course, I’m only a youngster, but I’m tough, and I can shoot and ride, and I had four years as a cadet, so I know the drill. It seems to me that any fellow who can be as useful as that has no right to stay behind … I want to do my bit.

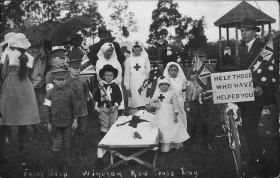

‘Doing their bit’ was the order of the day. The calendar was filled with ‘button days’ when war charities sold metal pins and buttons to support those in need: Wattle Day, Empire Day, Red Cross days, Rose Day, France’s Day, Soldier’s Day and War Orphans appeal days. Badges, pins, illustrated cigarette cards and embroidered postcards, emphasising loyalty to empire and the sacrificial bravery of Australia’s servicemen, were collected by children during the war.

Everyone seemed to be knitting, including small children. Frank Burrowes promised to knit his father a new woollen flannel, although he admitted he needed help from his aunt. As Frank and Ruth poured their daily lives out onto the page, they addressed letters to their father using a variety of nicknames:

Dear old Dad … Dear old dinky dumps … Dear young Dad … Dear old Bill … Dear old jam-tin … Dear Mr Jampot.

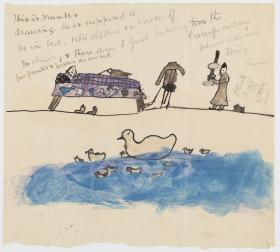

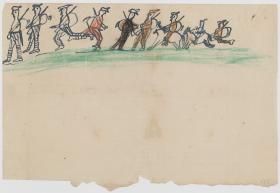

They wrote about the abundance of fruit and vegetables in their gardens, domestic crises of foxes getting into the chook pen, and the delight of heating bricks in the fireplace to warm their beds in winter. They sent drawings along with their letters: Ruth drew houses and flowers, while Frank illustrated his margins with soldiers and aeroplanes.

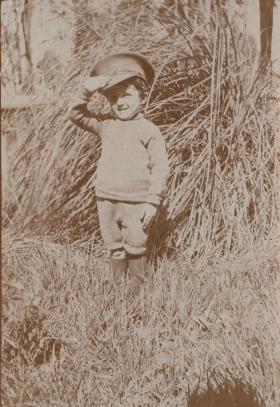

James Rollo Fry from Lindfield was only four years old when his older brothers Alan and Dene enlisted. He can be seen in the Fry family photograph album, standing in the garden as he proudly salutes from beneath his big brother’s army cap. On the Christmas postcard he sent Alan in 1915 he writes in large letters, ‘From Rollo with love’.

This June will see the centenary of the signing of the Versailles Peace Treaty, the formal end of the First World War. Celebrations and marches were held throughout the British Empire in the wake of the treaty. But we know that peace was short-lived.

After an adolescence filled with scouting adventures — including the World Scout Jamboree in Hungary in 1933 — Rollo, who as an adult preferred to be called Bill, worked as an accountant before enlisting with the Royal Australian Air Force in 1942 at the age of 31.

Frank and Ruth Burrowes joined the Australian Army, Frank serving in the Middle East, New Guinea and at Labuan Island, off Borneo, and Ruth in the nursing service. As a battle-hardened soldier, Frank included poems in letters to his mother:

No trumpet call — a blinding flash

That fills the world with flame.

And on an honour-roll somewhere,

Another golden name

Elise Edmonds

Senior Curator, Research & Discovery

This article was first published in SL magazine, Autumn 2019.