Authorities in both countries quickly discounted the claim, but just as fire scores its own path so too does fake news, sometimes leaping over digital containment lines into real life. In both countries a handful of politicians restated the bogus claim as fact, ingraining the falsehood in the minds of some and belying the effect of unprecedented heat in escalating all blazes, including the small number lit by arsonists.

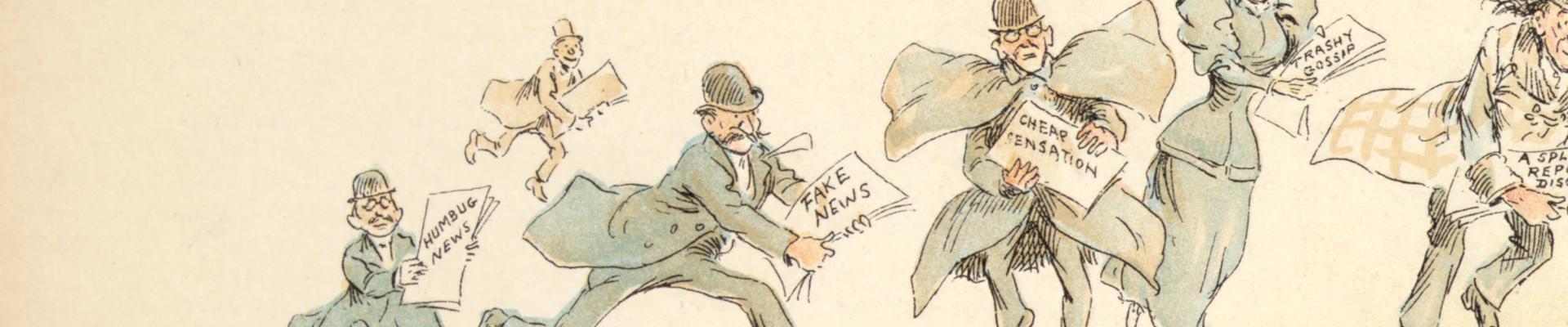

Whether wildfire or pandemic, disaster offers a fertile paddock for the sowers of misinformation. It creates doubt and distrust at a time when people need truth and certainty. Many blame social media but behind every false and malicious post is a human, or a human-programmed bot. Long before ‘post’ became a digital practice, those with a political, financial or merely mischievous intent traded in the lies and half-truths of fake news.

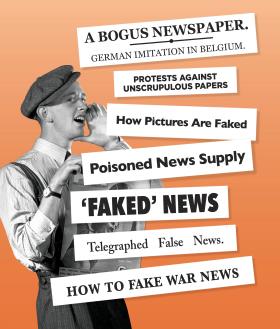

Not that it has always been known as fake news. Searches of digitised historic newspapers, such as those in the National Library of Australia’s Trove database, reveal the term ‘fake news’ was not in common usage until the middle of last century. It replaced ‘faked news’ as the preferred (and, perhaps, more accurate) term.

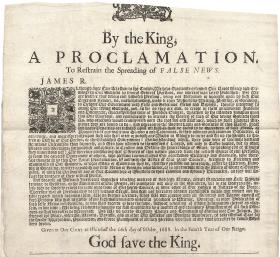

But for much of last century and, in fact, for many centuries before, ‘false news’ was the appellation for fabricated reports purporting to be news. Written in Middle English as ‘fal∫e news’, the term can be found in the first codification of English law, the 1275 Statute of Westminster. Known in Latin as scandalum magnatum, the spreading of false news was considered a political crime. ‘Devisors of tales’ who created ‘discord between the King and his People or great men of this Realm’ were to be imprisoned.

The law was often enforced. Records from London’s Newgate prison reveal several examples of people being punished for breaching the false news law. One was the servant Nicholas Mollere, who in 1371 was found guilty of ‘circulating lies’ that Newgate was to close and prisoners transferred to the Tower of London. Mollere was sentenced to an hour in a pillory, with a whetstone, normally used for knife sharpening, hung from his neck.

As the telegraph connected Australia throughout the 1850s, the Sydney Morning Herald New Year’s Day editorial of 1855 forecast the effect of that technology on false news: ‘It is instructive to see with what rapidity a great lie may gain the assent of the world … The telegraph will not, however, suffer a falsehood a long existence: its lightning speed soon overtakes the guilty error and condemns it. A few hours is the utmost duration of the best fabrication.’

The Herald was overly optimistic. Fake cable news was so prevalent by the early 1900s that, shortly before his death, journalist and poet William Thomas Goodge penned a poem titled ‘Cable Cooks’, published in the Brisbane Truth on 28 March 1909:

There’s nothing in this world escapes

The cove that cooks the cable ...

Most trivial incidents he shapes

And lends a lustrous label,

And fakes the news,

Which folks peruse

At every breakfast table ...

He may reside on Salisbury Plain,

Or here, on Weston-road, Balmain!

He may live in the Strand, but still.

Perhaps, his home’s at Marrickville!

Goodge’s suppositions as to the location of the ‘cable cook’ or news faker are strikingly similar to contemporary conjecture over ‘fake news factories’ — whether they’re in the Balkans or a Los Angeles suburb, where America’s National Public Radio ‘All Things Considered’ program tracked down a fake news operation in 2016. The reference in the poem to ‘every breakfast table’ suggests a similar saturation of fake news as found today.

By 1909 false news already had quite a history in Australia. The first identifiable instance was in 1827 when a ship carrying wheat from South America arrived in Sydney after false reports that the colony’s wheat crop had failed. The Australian argued for the ‘strongest reproaches. As it is, our censures ought to be directed against the proclaimers of false news — against those who created a false alarm, and made it be believed at a distance, that we were, or should be, in a state of actual want, unless timely arrivals averted the calamity.’

The rogue wheat arrival echoes practices of two millennia ago in Ancient Athens where corn and metal traders would attempt to inflate prices by inventing news of a storm or shipwreck or leaking a false report on the quality of the latest harvest.

Awareness of fake news did not curb its proliferation in Australian newspapers. As international tension mounted and erupted into the First World War in 1914, Australia may have been a hemisphere away from the battlefront but did not escape the proliferation of false reports that accompanied the crisis. Perhaps because of the distance and desperation for news of the conflict, newspapers of the era reveal a swathe of reports followed by corrected reports of sunk/not sunk warships, battle losses/gains and other supposed mishaps.

The Melbourne Argus of 30 September 1914 reported Prime Minister Andrew Fisher’s ire at the volume of fake news reports, which arrived daily, requiring Ministers to ‘spend a great deal of time denying them over the phone’. ‘The way some people are circulating false news of this kind is simply disgraceful,’ said the Prime Minister, ‘and those who are doing it should be punished severely … All I can say is that no person who loved his country would be guilty of spreading rumours of this kind.’

But as the Australian press sought to sate a war-news hungry public with as many reports as they could receive, the publication of fake news continued. It was especially hard to repel when the content came from respected overseas titles. And so, in April 1917, after the London Times and Daily Mail reported that the German army was running a ‘corpse utilization factory’, boiling down the bodies of dead German soldiers to extract fats for making fertiliser, lubricant and soap, more than 70 Australian newspapers immediately put the claim into print. In an effect similar to what we would call echo chambers today, many readers were predisposed to believing the German troops capable of committing such an atrocity and the story was widely accepted. The fact that some reports included Australian soldiers as witnesses furthered local interest.

The ‘corpse factory’ is one of the most infamous fake news stories of the twentieth century, running in newspapers around the world. While many newspapers, including some in Australia, outed the story as fake — either initially or in later years — it was still being reported as fact a decade later, even though the British Parliament had declared the story untrue in 1925. In recent years it has been argued that the prolonged uncertainty over the veracity of the claim contributed to delays in the international response to reported atrocities in Nazi Germany.

As we see today, fake news straddles the serious and the mischievous. It was also in 1925 that a false cable report, published in some American newspapers including the New York Times, told of boycotts and assaults on sailors that marred a visit of the United States naval fleet to Melbourne and Sydney. In fact more than 300,000 had turned out for a welcome parade. The report angered New South Wales Premier Jack Lang, who dispatched his own cable to the ‘Press of the United States’ rejecting the story and affirming that the fleet had received a warm welcome.

The historical record suggests that fake news proliferates most at times of national and global uncertainty. This explains its current manifestation, which exploits the rapid transmission of social media just as it did cable a century before.

In Australia, a search of historic newspapers reveals a relative lull in fake news until the Second World War when, once again, fake news operators peddled their wares to influence public opinion. A cartoon from the Melbourne Argus on 21 September 1946 reveals the extent of fake news at the time. Titled ‘Superman: False News’, the final triptych in a longer narrative shows that Lois Lane has left the Daily Planet to edit the Daily Sphere and falsely reports the running aground of a luxury liner. The final frame reveals that the Daily Planet’s circulation has tripled as readers avoid the fake stories in the Sphere. ‘Maybe Lois’ll be asking for her old job back, eh, chief!’ Clark Kent opines. ‘She seems to have flopped at editing the Sphere’. The fact this salvo was presented in cartoon form reveals general awareness, as there is today, of the ubiquity of fake news.

This ubiquity was challenged, and Australia would take a central role in the fight against fake news. In the aftermath of the Second World War, as countries came together to form the United Nations, fake news featured in its agenda of global problems to be addressed. The Australian delegate, former politician and judge Herbert Vere Evatt, was central in deliberations of the UN’s Political and Security Council.

The Soviet Union had submitted a motion urging increased press censorship and criminal penalties to curb war mongering. It named the United States, Turkey and Greece as the greatest offenders. Evatt proposed a different path and put forward an amended resolution calling on the UN to denounce war propaganda. He argued that ‘censorship and criminal penalties were an inadmissible way of dealing with war propaganda. The way to deal with war mongers was not to suppress them but expose them.’

Evatt’s ideal was to expand the reach of the responsible press, and give it full access ‘to the news and opinions in their own and other countries’. He proposed that governments provide practical assistance such as helping newspapers pay cable charges or, during newsprint shortages, making additional allocations of paper. His view was shared by the US and Britain, but conflicted with the Eastern Bloc countries, which wanted increased control and censorship.

Australia later withdrew, instead joining Canada and France in a similar proposal. The combined resolution condemned all forms of war propaganda and encouraged member nations to use any means available to disseminate information that encouraged peace. It received unprecedented support and was adopted unanimously by all 57 members of the UN political committee.

After considerable deliberation, and with Australian support, the UN passed The International Right of Correction, which allows countries to protest fake news to other governments and seek correction from publishers. The convention was formalized in 1952 and is still in force today, although relatively few countries — and Australia is not among them — are signatories.

Whether in 2020 or 1920, and one could go further to 1820 or 1720 and beyond, fake news has been a blight on the dissemination of news and information, increasing at times of societal fracture. It is during these times that fake news takes hold and, whether by cable or bytes, spreads like wildfire.

Dr Margaret Van Heekeren is a former journalist and lectures in Media and Communications at the University of Sydney.

This story appears in Openbook Summer 2020.