The extraordinary events of the past few months are unprecedented in our lifetimes, but the response to the Covid-19 pandemic contains echoes of the 1918–19 influenza outbreak. The Library is one of many institutions following the lead of our forebears.

When the Library announced its closure on Sunday 22 March 2020, it felt as though we were in uncharted waters: for the first time in memory the Library was closing its doors to the public and staff indefinitely. We would all be ‘self-isolating’, a term that had suddenly entered our vocabulary.

In the week before the Library closed, staff had begun to prepare for the inevitable shift to working from home by practising virtual meetings and saving files to the ‘cloud’. Reading room staff were working out how to offer services to readers remotely, and our cataloguing teams were preparing to access Library systems from home. Staff who acquire new material for the collection were monitoring social media and collecting posts with hashtags such as #stayhomeaustralia, #lockdownaustralia and #covid19australia, and archiving emails from businesses and organisations affected by the pandemic.

As ‘unprecedented’ as it all seems, this isn’t the first time the Library has closed for an extended period. For 10 weeks during the last great pandemic — the 1918–19 influenza, known as the Spanish flu — the doors remained shut. Described as ‘pneumonic influenza’, its symptoms included high temperature, aching joints, runny nose, cough and general fatigue, often leading to respiratory failure. It was highly infectious and frequently lethal.

The disease arrived in Sydney on 25 January 1919 via a soldier travelling by train from Melbourne. The soldier was quarantined at Randwick Military Hospital, but inevitably the influenza spread, first to the medical staff treating him, and then into the community. Within three days, the state government had announced the closure of schools, pubs, theatres, churches, libraries and other public places, with a proclamation in the Government Gazette:

[A]n infectious or contagious disease, highly dangerous to the public health, has broken out in NSW and it is desirable in the public interest and for the public safety to cut off all communication between persons infected with such disease and others of His Majesty’s subjects … I, Sir Walter Edward Davidson, the Governor … do hereby order all libraries, schools, churches, theatres, public halls and places of indoor resort for public entertainment in the Metropolitan Police District forthwith to close and be kept closed during such outbreak or until a further order be made … GOD SAVE THE KING!

Adhering to these strict regulations, Principal Librarian William Ifould and Mitchell Librarian Hugh Wright closed the General Reference Library (then on the corner of Bent and Macquarie streets) and the recently built Mitchell Library from 29 January to 2 March. In late February the regulations were relaxed and services returned to normal through March. But in April, a rise in the number of deaths saw the restrictions reinstated, and the Library closed for another five weeks from 4 April to 15 May.

Both libraries had seen steady increases in the number of readers for several years, and this had been cheerfully reported in annual reports. But 1919 was a different story: ‘Attendances at both the General Reference Library and the Mitchell Library were seriously affected throughout the first seven months of 1919 by the Influenza Epidemic and the regulations imposed by the Public Health Authorities.’

About one in three Australians were infected and nearly 15,000 died in less than a year. Those figures match the average annual death rate for members of the Australian Imperial Force through World War I.

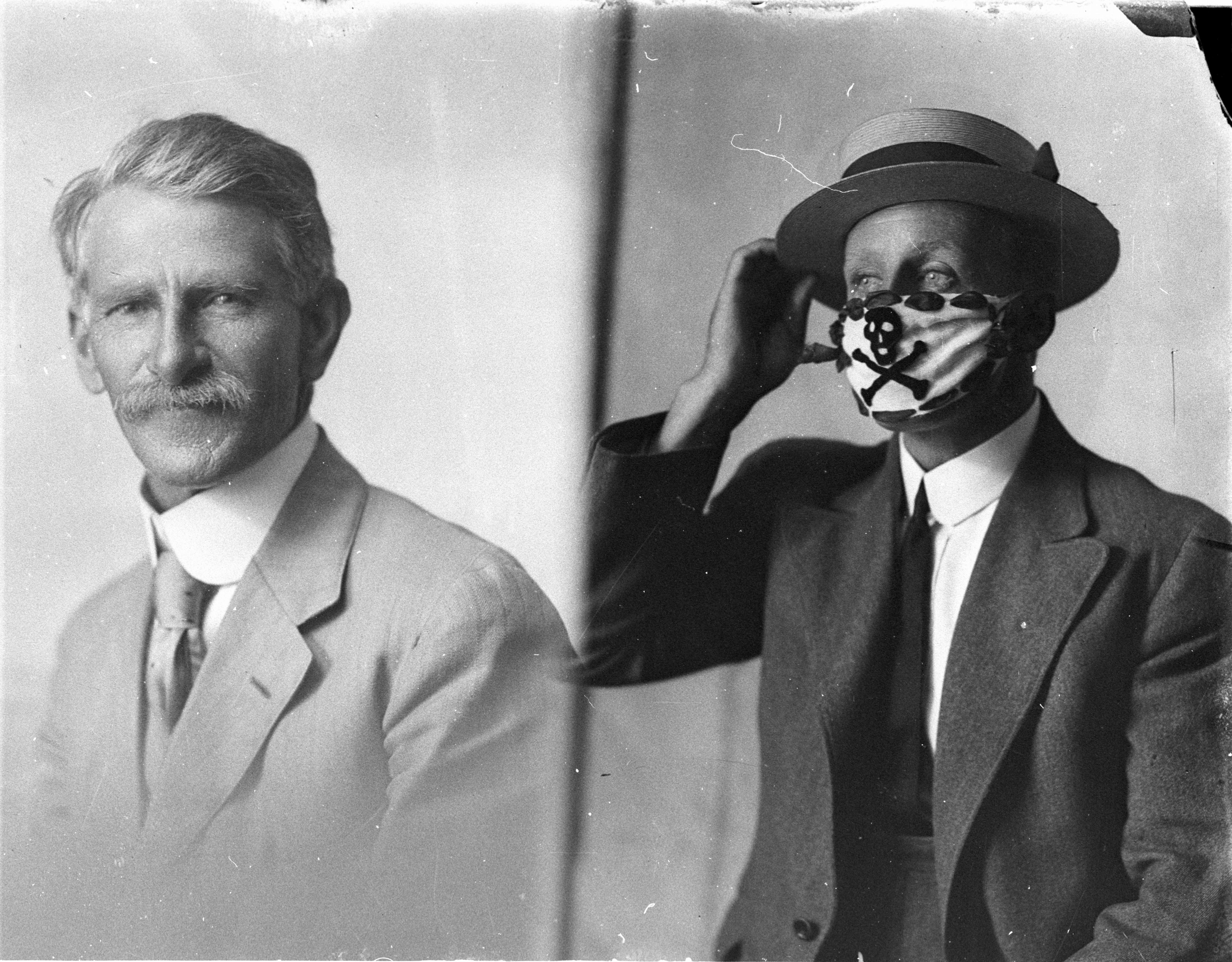

The entire Australian population felt the impact of the influenza: wearing muslin or gauze masks became an everyday necessity and people were urged to wash their hands frequently, stay in isolation and not panic.

‘[W]e should not lose our heads,’ the Sydney Morning Herald told its readers at the beginning of the outbreak, ‘we should keep our bodies clean and our spirits up. We should not create centres of contagion and should all remember that we are not only potential patients but potential carriers as well.’

Wise words from a century ago.

Elise Edmonds

Senior Curator, Research and Discovery