Each referendum produces lots of printed material which, of course, the Library collects.

Even in the digital age, there is no end to the printed material in our lives. Pamphlets, posters, booklets, beer mats, badges, menus, matchbooks (maybe not so many of those anymore) and stickers. Over decades, the Library has collected an immense assortment of these kinds of ephemera from elections, plebiscites and both state and federal referenda. As with each referendum before it, the upcoming Voice referendum will produce lots of material making the case for Yes or No.

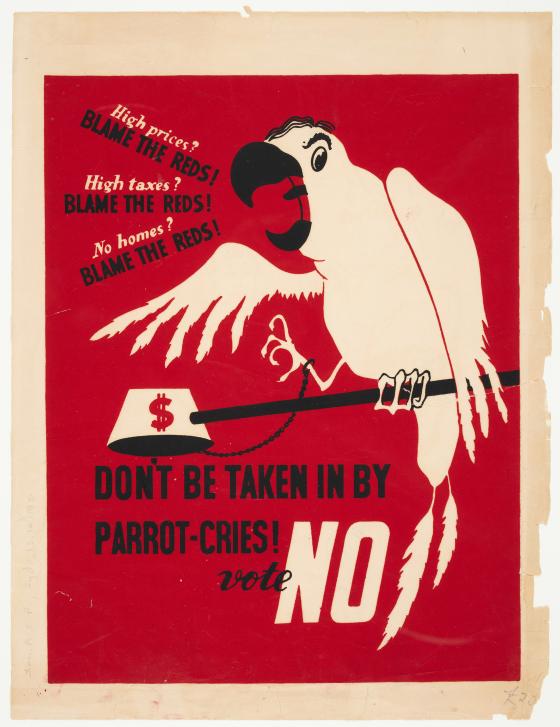

Much of this ephemera has been created to persuade, inform, or to promote ideas. Advertising is a central element of any referendum. Media philosopher Marshall McLuhan called advertising the greatest artform of the 20th century — many items in the Library’s vast collection support his case. A good example is the loud red poster screenprinted for the 1951 referendum (about powers to deal with communists and communism). It exclaims, ‘Don’t be taken in by parrot-cries! Vote No’.

Even printed material without artistic merit often has historical significance, as with the plain and straightforward ‘YES or NO?’ government pamphlet to inform voters ahead of the four questions posed at the referendum held in 1988. Typically, none of the proposals put to voters was carried.

Before the advent of online and social media, the most widely dispersed form of advertising was printed material. In 1999, the government spent approximately $48 million on Yes, No and Neutral campaign advertising for the Republic referendum. With the Voice referendum, each household will receive a booklet outlining the case. Through the enormous audience reach of printed ephemera, we can see the mechanics of persuasion from both sides of referendum campaigns, expressed in an often imaginative and visually striking format.

Short-lived but eminently collectable, ephemera convey the tastes and values of the times. Its functional quotidian format condenses ideas and information. So, it is well suited for referendums where voters are being asked specific and often complex questions. This complexity is perhaps one reason why only 8 of 44 referendums have ever been successful.

Referendum ephemera range from informative but bland official government literature, outlining both Yes and No campaigns, to outlandish black- and-white art that employs irony to lampoon the figures associated with either campaign. One example from the 1951 referendum splashes, ‘We don’t want fascism here!’

Thirty-three years later, alarmist tracts set beside photographs of Stalin and Hitler warned against Australia becoming a republic: ‘it is only a matter of time before a Dictatorship emerges’. This was in response to the 1984 referendum on the interchange of powers; had it passed it would have allowed the Commonwealth and the states to voluntarily refer powers to each other. In the same item, voters were presented with a ‘Republican Hall of Fame’ alongside profile shots of infamous potentates and undesirables.

Referendums are a form of direct democracy where the government asks for voters’ views on a specific question. As well as being necessary to alter the Australian Constitution (and thereforethe way our federal system of government works), they can afford a popular source of legitimacy for governments on contentious issues and can even take on a nation-building role when it is a question of social justice. The 1967 referendum to include Indigenous Australians in population counts demonstrated how Australia was able to move positively and with wholehearted agreement — the majority (90.77%) of voters said Yes. Fifty-six years later, Australia is again being given the opportunity to move towards greater constitutional recognition of First Nations peoples.

Various Yes and No campaigns have appealed to patriotic spirit, sometimes using well-worn symbols of hard-line nationalism that warn of the dangers of not voting one way or the other. In response to the 1984 referendum mentioned above, an ephemeral publication ‘Wake Up!’ was circulated by far-right group Council for a Free Australia, who rally against the ‘erosion of our traditional way of life’, beneath a proudly flying Southern Cross flag. The Australian flag often features as the embodiment of national identity. Campaigns for No often conflate various issues, for example, invoking the flag in the 1999 referendum. The question, about whether the nation should be a republic rather than a constitutional monarchy, had nothing to do with the flag.

According to constitutional lawyer Professor George Williams, the Constitution defines the political selfhood of the people. From this vantage point, constitutional politics is different to ordinary politics, reflected in the printed ephemera associated with it. Like election ephemera, referendum ephemera is passionate and persuasive, but is often wordier and more ruminative too, reflecting the complexities of unfamiliar and sometimes technical proposals. For example, during the well-known 1967 referendum — when people voted overwhelmingly to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for Indigenous people — there was a second question that proposed removing a requirement expressed by section 24 of the Constitution that there be a nexus between the sizes of the House of Representatives and the Senate. It failed.

In printed material, we see voters repeatedly confronted with the potentially horrific effects of allowing the government to amend the Constitution. War, dictatorships, a fascist police state, forced labour, martial law, or ‘Hitler-style powers’ are — allegedly — risked by those who vote Yes. These sentiments are reinforced through depictions of Nazi swastikas and ‘fat cat’ Prime Minister Robert Menzies copping a boot up the backside as we see in an item related to the contentious 1951 referendum. A cartoon caricatures ‘Dictator Bob’ replete with Nazi swastika armband, American dollar-sign medal, and a rap sheet enumerating the litany of his missteps relating to the Nazis, conscription and economic policy during the Depression.

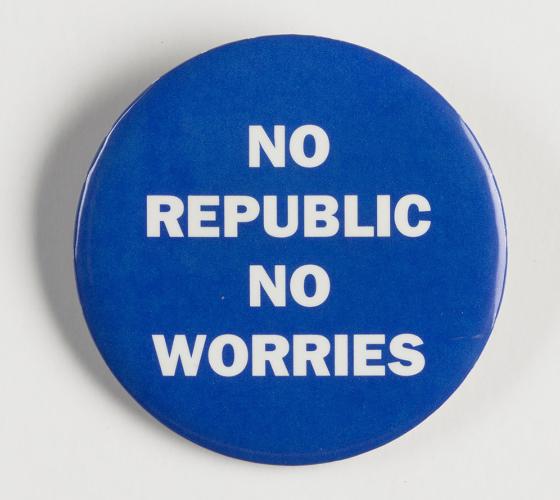

Much of the ephemera claims to reveal the hidden meaning of a proposal, revealing possible threats to freedom, using words such as the ‘dangerous fraud behind those innocent word’ that will deprive voters of their ‘birthright of freedom’. Conversely, the repeated use of a badge or badge motif denotes public pride in one’s stance on the matter and indicates that the decision is one which should be made definitively.

In printed material, we see voters repeatedly confronted with the potentially horrific effects of allowing the government to amend the Constitution.

A badge produced for the 1999 referendum on the republic is unequivocal: ‘No Republic No Worries’. Another item from the No campaign uses the immediacy of a cartoon format to neatly summarise its argument. The angry-looking republican mechanic is attempting to hoodwink honest Joe Blow. These kinds of portrayals of upright, mainly white, men and women fulfilling their roles as workers, soldiers, homemakers and child bearers evince an idealised Australian citizen. Simplicity of message is always key in ephemera, which is perfectly suited for an ‘If it aint broke don’t fix it’ message.

No constitutional referendum has ever succeeded without bipartisan support. Often it is the shadow of political agendas that seeks to confuse voters, or to at least sow uncertainty. The most successful Yes campaigns have built on a fundamental change in national attitudes. In 1967 there wasn’t an official No campaign. Other times, No campaigns have relied on fearmongering, on voters not understanding fully the proposal, and on voters’ inherent suspicion of politicians. A newspaper format perhaps lent authenticity to the declaration ‘1988: A Year of Danger’, when four questions were put to voters on parliamentary terms, fair elections, local government, and rights and freedoms. The ‘hidden agenda’ argument commonly appears in ephemera created by No campaigns and we see it being replicated in 2023.

Referendum ephemera captures the spirit of the moment and, like all material in the Library’s collections, is a record of human activity and the ways in which history is made. Libraries continue to collect digital ephemera: tweets, marketing emails, and website pop-ups and banners. Advertising formats in the 21st century may have changed, but the contents and language are surprisingly similar to what has gone before.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2023.

Andrew Trigg is a Specialist Librarian in Collection Acquisition and Curation.