Sex and censorship all at sea

In 1946, decades before Banned Books Week (26 September – 2 October) was launched, Robert S Close’s Love Me Sailor was ruled obscene and its author jailed. Set on a commercial sailing ship, or windjammer, the racy novel with its confronting tagline – ‘Thirty Men Vowed They’d Have Her’ – centres on the voyage of the lone woman on board.

Three Adelaide booksellers were prosecuted for selling Love Me Sailor; Close was found guilty of obscene libel and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and his publisher Georgian House was fined £100.

On appeal, the sentence was reduced and Close only served 10 days in prison, while the publisher’s fine was increased to £150.

Because of writing like this:

Then avid hands unbuttoned his coat. He was trembling. She drew his head down and he knew the warm, scented taste of her breasts. The gleaming candle of her body rose out of her drooped shift ... and drooped slowly, slowly ... as if wilting from the roaring heat in him, on the bed, on the pillows. He collapsed on her fumbling with wild urgency. Strange seas drew him into a cavern of warmth.

‘The decrepit English law under which I was sentenced to gaol for writing Love Me Sailor,’ Close declared in 1948, ‘could be used to imprison almost every other Australian author tomorrow.’

Close may have been exaggerating, but Love Me Sailor is an interesting instalment in the annals of censorship. Such was the outrage about sex in print that the book was not only banned, it was reportedly burned in public too. Writers and artists argued for Close’s right to publish, fighting to liberalise censorship in the postwar period. As Patrick Mullins points out, opponents to censorship felt that it was stifling debate and quashing new ideas.

Close himself decamped to Paris, joining libertarian artists and writers in the cafes of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. He returned to Australia in 1975, but two years later he moved to Majorca, where he died in 1995.

The Library holds a first edition of Love Me Sailor. It has a letter pasted inside, dated 23 September 1948, from journalist and writer Edwin James (EJ) Brady to Australian poet Roderic Quinn. Brady, who published Katherine Mansfield’s first short stories when he was editor of The Native Companion, writes to Quinn of stopping his contributions to The Bulletin, which he refers to as ‘the evil rag’, and his appreciation for the work of novelists Kylie Tennant and Christina Stead.

He also comments on the ‘rumpus’ caused by Love Me Sailor, which he had read in manuscript before it was published. While praising the book, Brady mentions that he had advised Close to ‘prune off some of the superfluous sex branches from the main stem’. But he believed the work should never have been prosecuted in court.

He also comments on the ‘rumpus’ caused by Love Me Sailor, which he had read in manuscript before it was published. While praising the book, Brady mentions that he had advised Close to ‘prune off some of the superfluous sex branches from the main stem’. But he believed the work should never have been prosecuted in court.

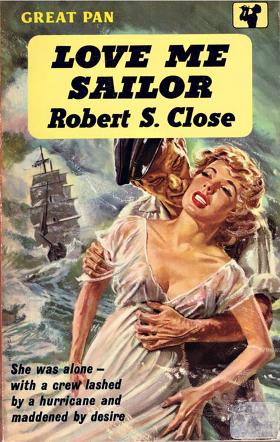

Close’s book is illustrated by Geoffrey Chapman Ingleton, a well-known Australian naval illustrator and writer. A collection of Ingleton’s etchings with working proofs and preliminary sketches made between 1937 and 1951 was bequeathed to the Library by Sir William Dixson in 1952. Later editions’ lurid jackets promised different attractions.

Times change: today, any ‘rumpus’ would come not from state agents of censorship, but from the voices of #MeToo.

Geoffrey Barker, Senior Curator.

This story appears in Openbook Spring 2021.